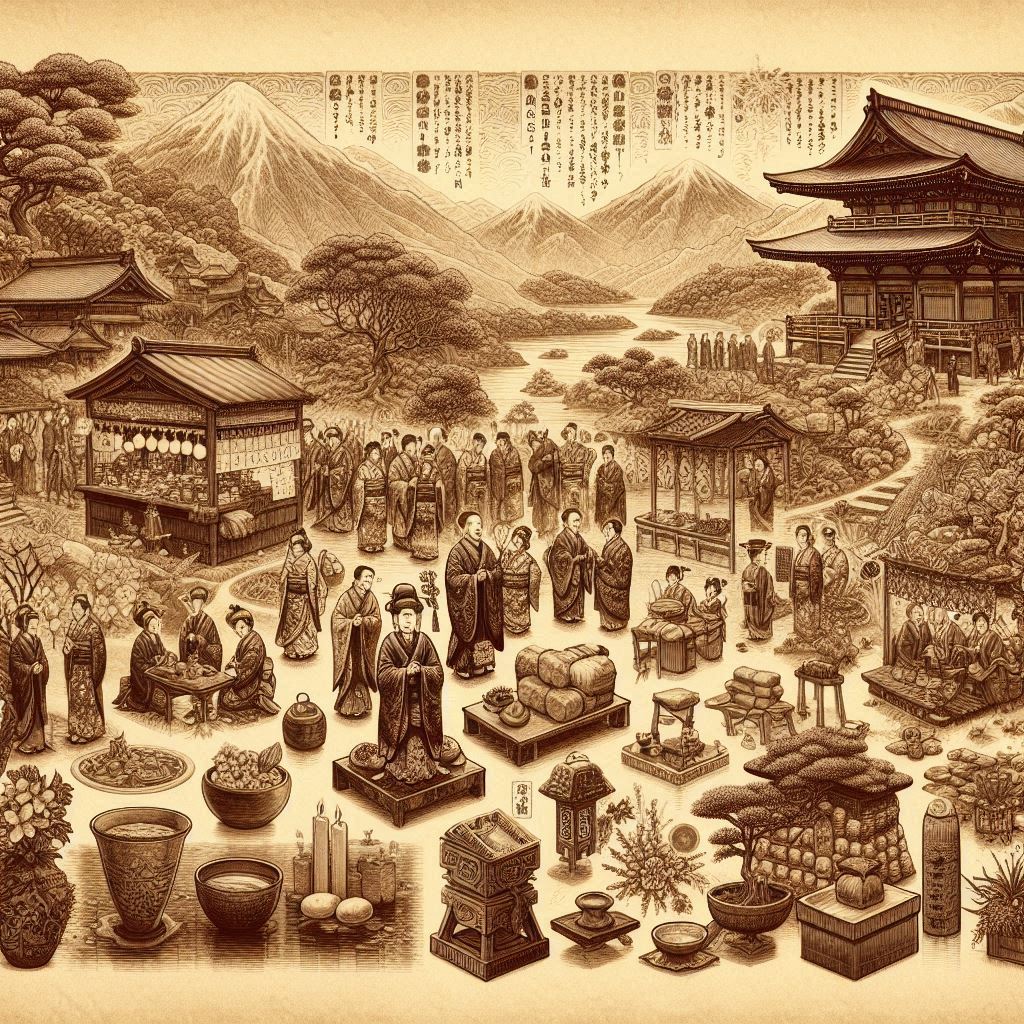

In Japan, the turning of the year, Shōgatsu, is more than a calendar event. It’s a spiritual reset, a season where the old is purified, the new is welcomed, and fortune is invited to linger. Rooted in Shinto beliefs, Buddhist practices, and centuries of folk tradition, the Japanese New Year blends reverence with celebration, creating a tapestry of rituals designed to secure happiness, health, and prosperity.

From the ringing of temple bells to the savoring of symbolic foods, each tradition carries a history stretching back generations, some to the Heian court, others to village shrines perched high in misty mountains. Here are eight key Japanese New Year customs and the meanings they carry.

1. Joya no Kane: The 108 Temple Bells

On New Year’s Eve, Buddhist temples ring their great bronze bells 108 times, a number representing human desires and worldly sins in Buddhist thought. With each resonant strike, a spiritual burden is lifted, cleansing the soul before the dawn of the new year. This practice, which emerged in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), teaches that renewal begins by letting go of the past.

2. Ōsōji: The Great Year-End Cleaning

In the final days of December, homes, businesses, and even shrines undergo Ōsōji, a thorough cleaning meant to sweep away the year’s misfortunes and make space for incoming blessings. The custom mirrors the Shinto principle of purity, dating back to agricultural cycles when homes were readied for the rice harvest gods.

3. Kadomatsu: Pine and Bamboo Gate Decorations

Tall arrangements of pine (longevity), bamboo (resilience), and sometimes plum blossoms (hope) are placed at gates or entrances from late December until January 7. Historically, these served as temporary dwellings for the Toshigami, the god of the new year, who bestows blessings on the household. The practice likely stems from Heian-period court rituals blended with rural fertility rites.

4. Osechi Ryōri: New Year’s Feast of Symbolism

Prepared before January 1 to avoid cooking during the first days of the year, Osechi Ryōri is a lacquered box of colorful dishes, each symbolic: black beans (health), herring roe (fertility), sweet rolled omelette (knowledge). This culinary art traces back to the early 9th century, when court nobles welcomed the year with sacred foods offered to the gods.

5. Otoshidama: New Year’s Gift Money

hildren eagerly await Otoshidama, envelopes of crisp bills given by parents, relatives, and close family friends. The tradition echoes samurai-era customs of presenting lucky rice cakes or tokens to younger generations, symbolizing the passing down of fortune and responsibility.

6. Hatsuhinode: First Sunrise of the Year

Many rise before dawn on January 1 to witness the Hatsuhinode, often from mountaintops, beaches, or shrine steps. The belief that seeing the first sunrise brings health and success has roots in Shinto sun worship and agricultural rites honoring Amaterasu, the sun goddess.

7. Hatsumōde: First Shrine or Temple Visit

Between January 1–3, people visit Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples for Hatsumōde, offering prayers for safety, success, and happiness. Popular shrines like Meiji Jingu in Tokyo see millions of visitors. This tradition began in the Edo period, evolving from local village rites to a nationwide spiritual pilgrimage.

8. Kakizome: First Calligraphy of the Year

On January 2, Kakizome, the “first writing”, sees participants brush auspicious kanji or poems onto fresh paper. The act, which began among court scholars during the Heian era, is said to manifest the writer’s hopes into reality.

Origins of the Japanese New Year Traditions

Before adopting the Gregorian calendar in 1873, Japan celebrated New Year in early spring, much like the Chinese lunar calendar. Shinto, with its seasonal cycles and reverence for purity, merged seamlessly with Buddhist philosophies of renewal and release. Over centuries, courtly elegance, samurai discipline, and rural folk beliefs fused to form the layered customs we see today.

Each tradition reflects a deep relationship with nature, community, and the divine, recognizing that fortune is not a random gift but the fruit of respect, intention, and gratitude.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What does ringing the temple bell 108 times during Joya no Kane symbolize?

A1: It represents cleansing 108 worldly desires to start the new year pure.

Q2: What is the purpose of Ōsōji before New Year in Japan?

A2: To remove the year’s misfortune and welcome good fortune.

Q3: What do pine and bamboo in a kadomatsu represent?

A3: Pine symbolizes longevity; bamboo represents resilience.

Q4: What is Osechi Ryōri?

A4: A traditional Japanese New Year feast where each dish carries symbolic meaning for health, wealth, or happiness.

Q5: Why do people watch the first sunrise, or Hatsuhinode, in Japan?

A5: To invite health, success, and blessings from the sun goddess Amaterasu.

Q6: What is Kakizome and when is it practiced?

A6: The first calligraphy of the year, done on January 2 to express hopes and intentions.