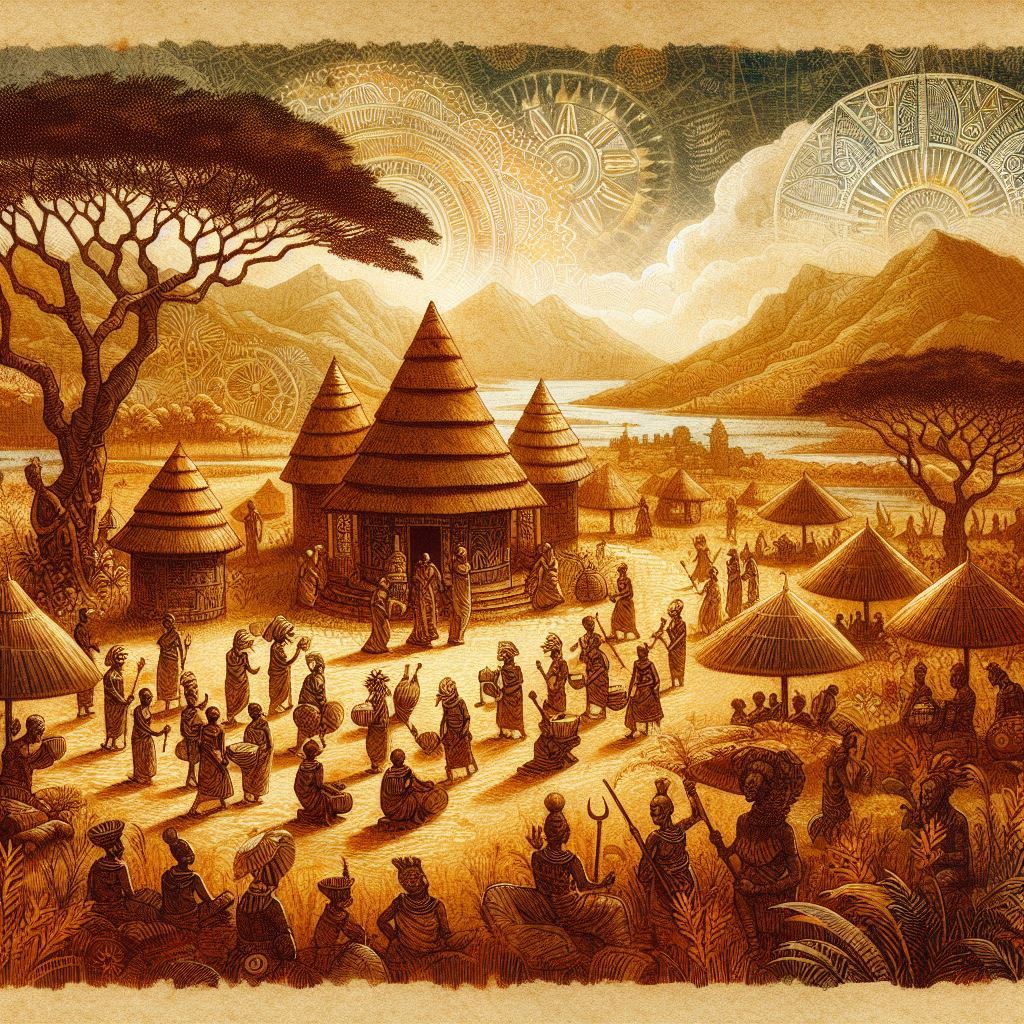

When the rains have come and gone, and the earth has pushed forth her bounty, the villages of West Africa hum with the rhythm of gratitude. Across golden fields of millet and yam mounds rising like small hills, the people prepare for the harvest festivals, days and nights of music, offerings, and prayers that tie the living to their ancestors, the land, and the spirits who watch over both.

The harvest is not just a season. It is a covenant. These nine rituals, rooted in centuries of tradition, bless the first fruits and ensure abundance for the year to come.

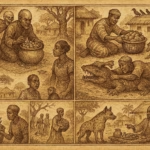

1. The First Yam Offering

In Igbo lands of Nigeria, the very first yam pulled from the earth is not eaten but offered to the gods and ancestors. It is washed, wrapped in palm leaves, and placed before the village shrine, accompanied by kola nuts and palm wine. Only after the elders taste this offering do the people begin their feast. To eat yams before this ritual is to court bad luck and spiritual dishonor.

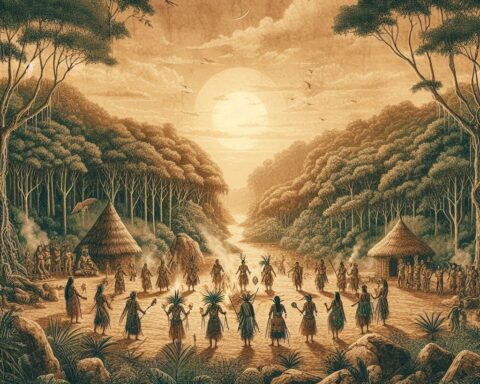

2. Harvest Dance of the Hands

Among the Ashanti of Ghana, dancers paint their palms with white clay and move in circles, clapping in intricate rhythms. The sound is said to “wake the spirits” who guard the crops. Each clap is a thank-you, each stomp a request for rain in the coming year. The young watch the elders’ steps, learning that gratitude is an act one performs with the whole body.

3. Libation Ceremony

In villages from Sierra Leone to Senegal, the harvest begins with libations. The chief pours water, palm wine, or millet beer onto the soil, murmuring blessings in the language of the ancestors. Some words are old, so old that their meanings are known only to the spirits. This act reminds the people that every sip they take was first a gift from the earth.

4. Presentation to the Chief

Bundles of maize, calabashes of oil, and baskets of cassava are carried in procession to the village chief. He receives them not for personal wealth, but to symbolize that the harvest belongs to the community. In return, he blesses the farmers and proclaims the official opening of the feast. The chief’s role is both earthly and spiritual, he is the bridge between the people and the unseen.

5. River Offerings

Along the Niger River, fishermen and farmers alike set small wooden bowls afloat, carrying maize, groundnuts, and coins. These are offerings to the water spirits, who control the rains and the fertility of the soil. Children watch their elders release the bowls into the current, learning that the river is not just water, it is life, memory, and the road to the ancestors.

6. Masked Ancestors

The Dogon of Mali bring out towering masks, some over 15 feet high, representing ancestral spirits. The mask dancers weave through the crowd, blessing fields with sweeping gestures. The belief is simple yet profound: the ancestors walk among the living during the harvest, and through dance, they give their strength back to the land.

7. Communal Feast

At nightfall, the village gathers for a great feast. The air fills with the scent of groundnut stew, roasted plantains, and spicy jollof rice. Meat, often rare during the year, is shared freely. Elders tell the children: “When you share your food, you share your fortune.” The first plate is often set aside for the ancestors, left beneath a tree or beside the hearth.

8. Fire Circle Storytelling

As the moon rises, a great fire is lit. Elders tell stories of how the first seeds were given to humans by the gods, and how disobedience once brought famine. Laughter and song rise into the night. These tales are not merely entertainment, they are living lessons about respect for the land, humility, and the price of greed.

9. Closing Song to the Earth

Before dawn, women gather in the fields to sing to the earth. Their voices rise in harmonies that mimic the wind, calling for a fertile year ahead. The words are part prayer, part praise, and part promise: “As we feed you, Mother, so you will feed us.” With the song’s end, the festival closes, and the cycle of planting begins anew.

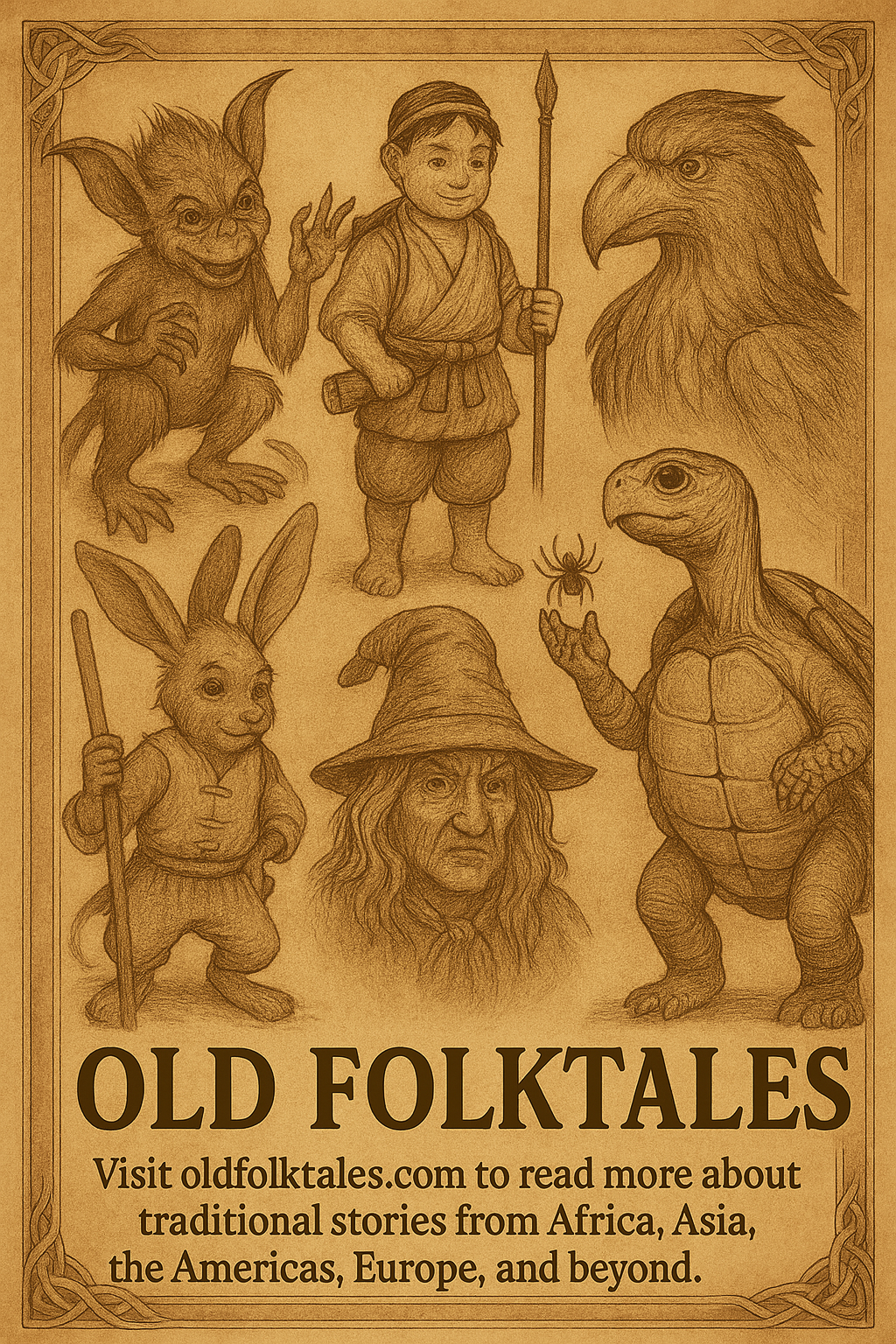

Origin of West African Harvest Rituals

Harvest rituals in West Africa are as old as agriculture itself, rooted in animist traditions that predate recorded history. Across the region, from the Yoruba of Nigeria to the Mandinka of Senegal, these ceremonies evolved from the belief that the earth, rivers, and skies are inhabited by spiritual forces. Offerings and dances were ways to maintain harmony with these forces, ensuring that famine did not follow feast.

Colonial contact and the spread of Christianity and Islam adapted, but did not erase, these traditions, many communities still blend ancestral rites with modern religious practices. Today, harvest festivals remain not just agricultural events but vital expressions of cultural identity, weaving together the living, the ancestors, and the land in one continuous cycle of gratitude.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What is the purpose of the First Yam Offering?

A1: To honor the gods and ancestors before the community eats from the harvest.

Q2: Why do Ashanti dancers paint their hands white during the Harvest Dance?

A2: The white symbolizes purity and spiritual connection while clapping thanks to the spirits.

Q3: What is poured during the Libation Ceremony, and why?

A3: Water, palm wine, or millet beer is poured to bless the earth and honor the ancestors.

Q4: What is the role of the chief during the Presentation to the Chief ritual?

A4: To symbolize that the harvest belongs to the whole community and to bless the farmers.

Q5: What do River Offerings represent?

A5: Gratitude to water spirits for rain, fertility, and life.

Q6: Why are stories told during Fire Circle gatherings?

A6: To teach moral lessons about respect for the land and community through ancestral tales.