In the coastal villages of Benin, when the sun sets and the sky deepens into indigo, the people light their lamps and gather close. From afar, the sound of drums rises, steady and powerful. The rhythm calls not for dance alone, but for the coming of the Zangbeto, the sacred spirits of the night.

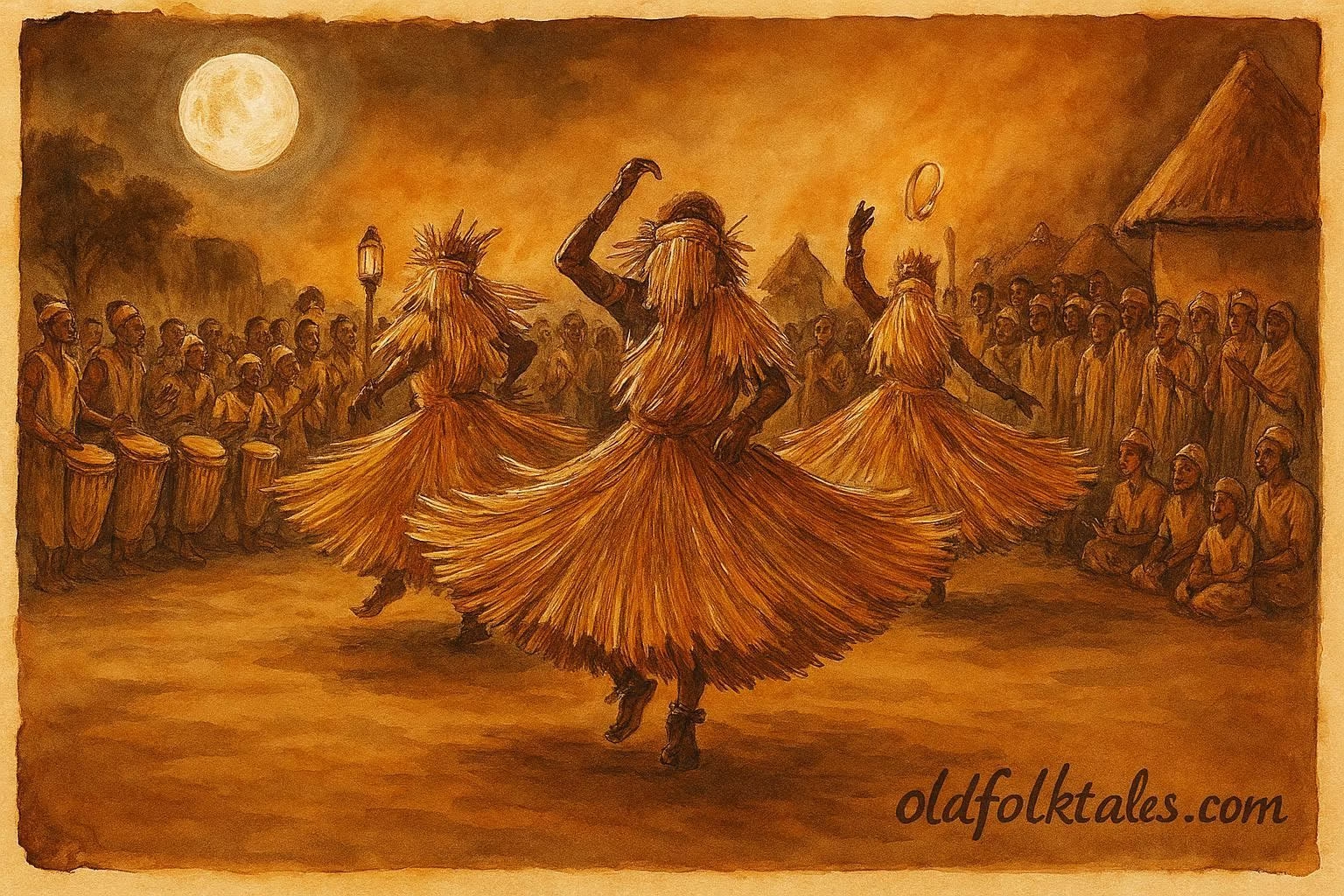

They appear as towering figures made of palm fibers and raffia, spinning and gliding across the earth. No human face can be seen beneath their woven cloaks. To the faithful, they are not costumes or masks, but the living vessels of ancestral spirits. When they emerge from the darkness, the people bow, for it is said that the true spirit of justice walks among them.

The legend of the Zangbeto is one of guardianship, order, and sacred duty. Long ago, before villages had written laws, it was the Zangbeto who kept peace in the night. They were believed to be the spirits of ancient ancestors who vowed to watch over their descendants. Their name, in the Goun and Fon languages, means “men of the night,” though they are more than men they are the breath of the unseen world.

Encounter dragons, spirits, and beasts that roamed the myths of every civilization

One such tale tells of a time when a village on the edge of Lake Nokoué was plagued by thefts and misfortune. Fishermen found their nets torn, and women’s market goods vanished before dawn. Fear spread quickly, for the people believed that witchcraft had entered their midst.

One evening, as the moon rose full and golden, the chief called for the Zangbeto society to perform their vigil. The drummers gathered, beating out the sacred rhythm that echoes through centuries. The villagers stood in a circle, torches held high, as three great figures emerged from the darkness. Their raffia cloaks shimmered like waves under the firelight.

The Zangbeto began to spin. Slowly at first, then faster, until their forms blurred into whirling pillars of gold and shadow. The air trembled with power. The people fell silent as the leader of the society stepped forward and chanted the words that invited the spirits to speak.

Then, from within the largest figure, a deep voice emerged a sound that was not human. “There is one among you who hides the truth,” it said. The villagers glanced at one another, fear creeping across their faces. “Tonight, justice shall reveal itself.”

The Zangbeto turned toward a hut near the water. The drumming stopped. The figure spun once more and suddenly collapsed to the ground. When the elders lifted its raffia covering, there was no body beneath, only a bowl of ashes and a carved wooden charm. The people gasped.

From the crowd stepped a young man, trembling. He confessed that he had stolen from the fishermen to pay a debt to a witch doctor. He wept, begging for forgiveness. The elders ordered purification rites, and the Zangbeto rose again, whole and shining, as if reborn. The drums resumed, this time in celebration, and the people thanked the spirits for restoring balance.

Since that day, the villagers have called upon the Zangbeto whenever the community’s peace is threatened. They believe that no lie can survive before the spirits’ gaze. Their rituals are not only for punishment but also for protection. When illness strikes, when storms destroy the crops, or when quarrels divide families, the drummers summon the Zangbeto to restore harmony.

During festivals, they whirl through the streets, their movements so fast that children believe they float above the ground. Offerings of palm wine, kola nuts, and food are laid before them as the crowd chants blessings. Women ululate, men clap in rhythm, and all eyes watch as the sacred watchers pass by.

Though some outsiders claim that men hide beneath the raffia, those who have witnessed the Zangbeto’s mystery swear otherwise. They tell of moments when a cloak fell open and nothing but wind rushed out, or when firelight shone through and revealed no human shape. To believers, the Zangbeto are not to be explained they are to be honored.

Even today, the Zangbeto remain central to the Vodún faith of Benin and Togo. They are symbols of truth, guardians of night, and protectors against witchcraft and wrongdoing. Their presence teaches that justice is not merely human law but the harmony between the living and the spirit world.

When the drums call at dusk and the raffia figures begin to turn, the people know that the ancestors are awake. The Zangbeto watch from the shadows, unseen yet ever near, ensuring that the world of men walks rightly under the gaze of the unseen.

Author’s Note

The Zangbeto embody one of the most profound truths in West African spirituality that justice is both a human and divine responsibility. Through their mysterious dances and unbroken silence, they remind communities that honesty, peace, and faith hold societies together. Whether viewed as ancestral spirits or symbols of order, the Zangbeto stand as a living testament to the unity of law and spirit.

Knowledge Check

1. Who are the Zangbeto in Beninese and Togolese tradition?

They are night guardians and ancestral spirits who protect villages and maintain justice.

2. What materials are used to create the Zangbeto figures?

They are woven from raffia and palm fibers, forming tall, spinning figures that represent spirit vessels.

3. What happened when the Zangbeto were summoned to the lakeside village?

They revealed the identity of a thief through spiritual intervention and restored balance to the community.

4. Why do villagers honor the Zangbeto with music and offerings?

To show respect for their role as sacred guardians and to seek their blessing for peace and protection.

5. What lesson does the Zangbeto legend teach about justice?

That truth is guided by divine power and community harmony, not just by human punishment.

6. How do the Zangbeto remain relevant in modern times?

They continue to serve as cultural symbols of vigilance, morality, and spiritual order in Vodún practice.