Each summer, when the first ears of corn swell green on the stalk, many Southeastern nations gather for the Green Corn Ceremony (often called “Busk” by Muscogee/Creek speakers). At once harvest rite, public purification, and political covenant, the Busk marks a cyclical return: the people restore ceremonial fires, ask forgiveness, renew kin ties, and give thanks for corn and the life it sustains.

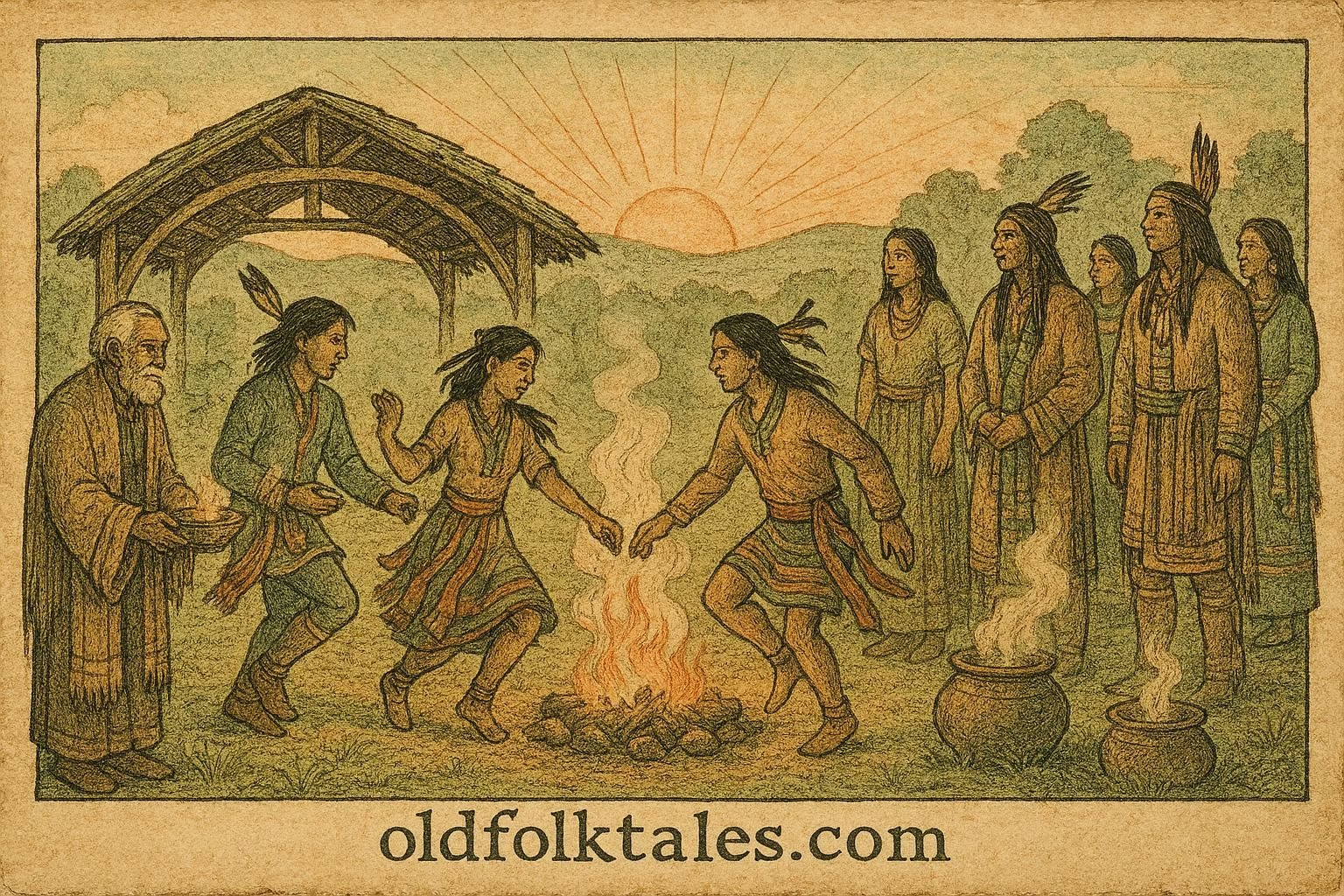

Communities prepare weeks in advance. Families clean houses; leaders select a central ceremonial ground; drums and singers rehearse the seasonal songs; and elders settle logistics for visitors. The core days typically include waking at dawn, communal fasting, the extinguishing and rekindling of the sacred fire, ritual bathing or sweat-lodge purification, and public exchanges of apology and forgiveness. Dance, feasting, and the sharing of the new corn follow. A Green Corn longhouse, or central open arbor, becomes the stage for speeches that rehearse lineage obligations and rehearse the people’s moral commitments.

The ceremony is civic as well as sacred. Councils use the Busk to promulgate laws, resolve disputes, and reassert leadership roles. Gift-giving and the public redistribution of food convert spiritual blessings into tangible social support. In many towns a “busk” is also a calendrical marker: when the green corn is ready, the community measures itself anew.

Mythic connection and cosmology

Corn (and related cultivated plants) occupies a sacred place in Southeastern cosmologies. Many communities hold origin narratives in which people and plants are kin: corn is not merely food but a living relative that sustains life. The Busk enacts that kinship. By offering the first fruits and rekindling the communal fire, people acknowledge dependence on both plant and spirit worlds. Ritual bathing and confession restore spiritual cleanliness so that the community may accept the new growth without offense.

The extinguishing and relighting of the fire is especially charged. The sacred fire, caretaken by lineage stewards, symbolizes continuity with ancestors and the life-force of the nation. To “put the fire out” for a brief interval is to close a moral account: grievances are aired and forgiven, debts of insult or injury are recognized, and then the community relights the hearth as a renewed covenant. That act dramatizes reciprocity: the people promise proper stewardship and right social conduct; in return they receive abundance.

How it was practiced — rites and sequences

Ritual sequences vary by nation and town, but certain elements recur. Many Busks begin with fasting and a night of vigil. An early-morning council calls for the extinguishing of all household hearth fires; elders carry embers to a central bonfire, which is then ceremonially put out. Delegations may visit neighbors to exchange apologies; a formal “cleansing” may involve sweat lodges, pond or river bathing, and ritual songs to drive off illness or disharmony.

At mid-ceremony the central fire is rekindled, often from a sacred ember preserved across seasons, and new corn is cooked and distributed. Dance and reciprocal gift-giving follow, with young people dancing while elders observe and offer counsel. The ceremony closes with a feast: the people eat the first-boiled corn together, demonstrating the redistribution of thanksgiving.

Because the Busk also consolidates political life, leaders may declare new rules, settle land matters, or reassert clan responsibilities. Visitors from allied towns bring greetings and songs; children learn the songs, dances, and obligations that sustain the nation.

Social meaning and continuity today

Contact, missionization, and U.S. policies disrupted many ceremonial calendars. Christianization altered public language and some ritual forms; allotment and removal scattered towns. Yet the Green Corn Ceremony endured in pockets, and 20th–21st-century revitalization projects have brought it back to public prominence. Contemporary Busks sometimes blend Christian prayers with traditional songs, but their core remains: renewal, forgiveness, and community cohesion.

Today the ceremony also affirms identity. In the face of historical loss, the Busk is a teacher: it transmits language, songs, and the responsibilities of kinship. For many towns the Green Corn Ceremony is an act of survival, an assertion that the people remain responsible stewards of their fields, waters, and ceremonial fires.

Author’s Note

The Green Corn Ceremony is as much a moral school as a harvest festival. Its central lesson, repair what is broken before accepting new blessings, offers a public ritual grammar for living together. This account follows publicly available sources and community descriptions; where ceremonies remain private, those restrictions should be respected. If you seek deeper study, consult tribal cultural centers and community-sanctioned publications.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What seasonal sign triggers the Green Corn Ceremony?

A: The ripening of the first ears of corn, green, not yet fully mature, is the traditional signal.

Q2: Why is the sacred fire extinguished and then relit?

A: Extinguishing marks a time for confession and cleansing; relighting renews communal covenant and continuity with ancestors.

Q3: Name three core functions of the Busk.

A: Purification, thanksgiving for first-fruits, and social/political renewal (forgiveness, law-making).

Q4: How does the ceremony link cosmology and daily life?

A: By treating corn as kin and making the care of fields part of reciprocal obligations with spirit and ancestral worlds.

Q5: How did historical pressures affect the Green Corn Ceremony?

A: Colonization, missionization, and forced relocations disrupted practice, but ceremonies persisted and have been revived.

Q6: How should outsiders approach learning about the Busk?

A: With respect, use tribal publications, attend public portions only with invitation, and follow cultural protocols.