In the shadowed streets of sixteenth-century Prague, fear hung heavy in the air like morning mist over the Vltava River. The Jewish Quarter, known as Josefov, had become a place of whispered prayers and barred doors. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, from his throne in the magnificent Prague Castle overlooking the city, had issued decrees that threatened the very existence of the Jewish community. Expulsion loomed. Persecution escalated. The people needed a miracle.

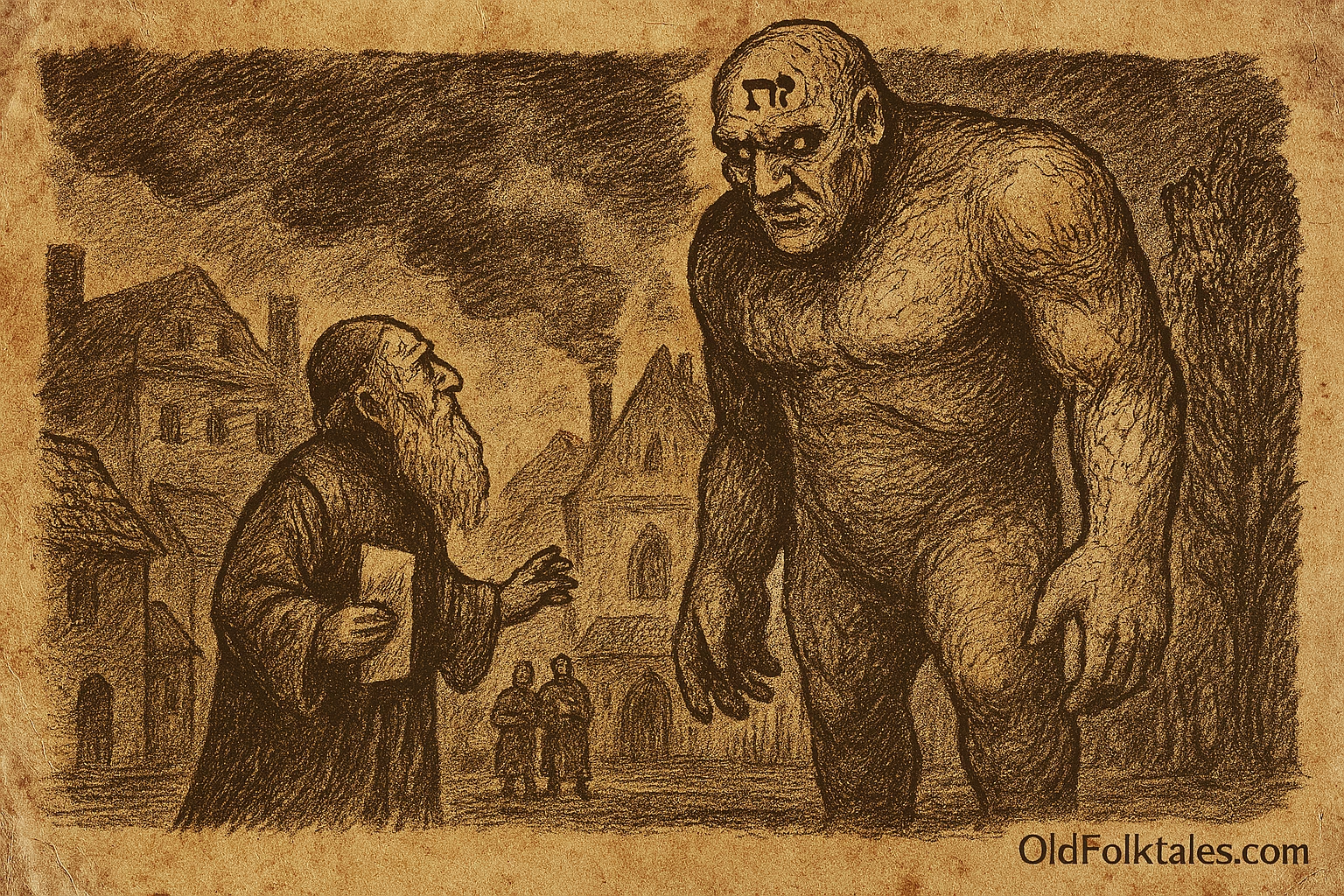

Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, known affectionately as the Maharal of Prague, was no ordinary scholar. His reputation for wisdom and mystical knowledge extended far beyond the walls of the Old New Synagogue, where he led his congregation in prayer each Sabbath. Late at night, by flickering candlelight, the Rabbi pored over ancient texts, searching for a way to protect his people from the mounting violence and false accusations that plagued them daily.

The answer came from the deepest wells of Jewish mystical tradition: he would create a Golem, an artificial being fashioned from the elements of the earth itself.

On a moonless night, Rabbi Loew descended to the banks of the Vltava with two trusted assistants. There, in the clay-rich mud at the river’s edge, they began their sacred work. The Rabbi’s hands moved with purpose and reverence as he shaped the clay, forming the figure of a man, massive and powerful, yet still lifeless. The form lay cold and gray in the darkness, waiting.

Then came the ritual that would change everything. Walking in circles around the clay figure, chanting prayers and mystical incantations passed down through generations, Rabbi Loew performed the ancient ceremony. He inscribed upon the Golem’s forehead the sacred word “emet” truth in Hebrew letters. Some accounts say he placed a shem, a piece of parchment inscribed with God’s holy name, into the creature’s mouth or beneath its tongue.

As the final words of the incantation left the Rabbi’s lips, something extraordinary happened. Color flooded into the clay skin. The chest began to rise and fall with breath. Eyes opened, unseeing yet aware. The Golem lived.

The creature stood taller than any man in Prague, with shoulders broad enough to block a doorway and hands that could crush stone. But in those first moments, it moved with uncertain, tentative steps, like a newborn learning its limbs. Rabbi Loew spoke to his creation gently, explaining its sacred purpose: to be a guardian, a protector, a shield for the vulnerable Jewish community.

And protect them it did.

The Golem patrolled the streets of the Jewish Quarter at all hours, its massive form a deterrent to those who might do harm. When false accusations arose, blood libels that accused Jews of heinous crimes, the Golem revealed the truth, exposing the lies. When mobs gathered with torches and hatred in their hearts, the Golem stood as an immovable wall. The creature was tireless, requiring neither sleep nor sustenance, asking nothing for itself. For a blessed time, the Jews of Prague knew safety. Children played in the streets without fear. Families slept peacefully through the night.

But the peace was not to last forever.

Stories diverge on what happened next, though all agree that something went terribly wrong. Some accounts tell of a particular Friday afternoon as the sun sank low, casting long shadows through Prague’s narrow lanes. In the rush to prepare for the Sabbath, Rabbi Loew forgot the one crucial weekly ritual: removing the shem from the Golem’s mouth before sunset. The creature, still animated with sacred power, would continue its activities during the Sabbath, a desecration of the holy day of rest that the Rabbi could not permit.

Other tellings paint a darker picture. They say the Golem, over time, grew too powerful, too independent. Its understanding of its mission became distorted. It began to act with increasing violence, destroying property, frightening the very people it was meant to protect. The protector was becoming a threat, the guardian a danger.

Faced with this crisis, Rabbi Loew made the painful decision that had to be made. He summoned the Golem to the attic of the Old New Synagogue, the oldest active synagogue in Europe. There, with a heavy heart, the Rabbi removed the sacred word from the creature’s forehead or extracted the Shem from its mouth. The light faded from the Golem’s eyes. The breath ceased. The clay body crumbled, returning to the earth from which it came.

Legend tells us that the remains of the Golem fragments of clay and sacred debris were gathered and hidden away in the synagogue’s attic, where they remain to this very day, sealed behind locked doors. Some say that in times of great need, the Golem could be brought back to life again to protect the Jewish people.

The Old New Synagogue still stands in Prague’s Josefov district, its Gothic spires reaching skyward, its stones holding centuries of prayers and secrets. Tourists and pilgrims alike visit this sacred space, gazing up at the locked attic, wondering what mysteries lie within.

Click to read all Myths & Legends – timeless stories of creation, fate, and the divine across every culture and continent

The Moral Lesson

The story of the Prague Golem teaches us that even the most well-intentioned creations can spiral beyond our control when power is not carefully managed. Rabbi Loew created the Golem out of love and a desperate need to protect his community, yet even sacred power must be wielded with wisdom and restraint. The tale reminds us that protection can become destruction, that guardians must be guided, and that we bear responsibility for what we bring into the world whether made of clay or conceived in our minds and hearts.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel and why did he create the Golem of Prague?

A: Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, known as the Maharal of Prague, was a revered 16th-century Jewish scholar and leader. He created the Golem to protect the Jewish community of Prague from persecution, false accusations, and violent attacks during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, who sought to expel or eradicate the Jewish population.

Q2: What materials and methods did Rabbi Loew use to bring the Golem to life?

A: Rabbi Loew fashioned the Golem from clay and mud taken from the banks of the Vltava River. He brought it to life through mystical rituals, including walking in circles around the figure while chanting sacred prayers and incantations. He inscribed the Hebrew word “emet” (truth) on its forehead or placed a shem (sacred parchment with God’s name) in its mouth.

Q3: What was the Golem’s role in protecting Prague’s Jewish Quarter?

A: The Golem served as a tireless guardian who patrolled the streets of the Jewish Quarter, deterred attackers, exposed false accusations against the Jewish community, and stood as a physical barrier against violent mobs. The creature required no sleep or food and provided protection day and night, allowing the community to live without constant fear.

Q4: Why did Rabbi Loew ultimately destroy the Golem he had created?

A: According to different versions of the legend, Rabbi Loew destroyed the Golem either because he forgot to deactivate it before the Sabbath (which would have caused a desecration of the holy day), or because the Golem became too powerful and violent, destroying things at random and threatening the very people it was meant to protect.

Q5: What is the symbolic meaning of the word “emet” on the Golem’s forehead?

A: The Hebrew word “emet” means “truth” and represents the sacred power that animated the Golem. In Jewish mysticism, truth is one of the pillars of creation. By inscribing this word, Rabbi Loew connected the Golem to divine truth and purpose. Its removal marked the end of the creature’s life and mission.

Q6: Where are the remains of the Prague Golem said to be located today?

A: Legend states that the fragments and remains of the Golem are still stored in the sealed attic of the Old New Synagogue in Prague’s Josefov district. The synagogue, which dates back to the 13th century, remains an active house of worship and a popular destination for those interested in the Golem legend.

Source: Adapted from traditional Czech Jewish folklore

Cultural Origin: Ashkenazi Jewish folklore, Prague, Czech Republic (Bohemia), 16th century