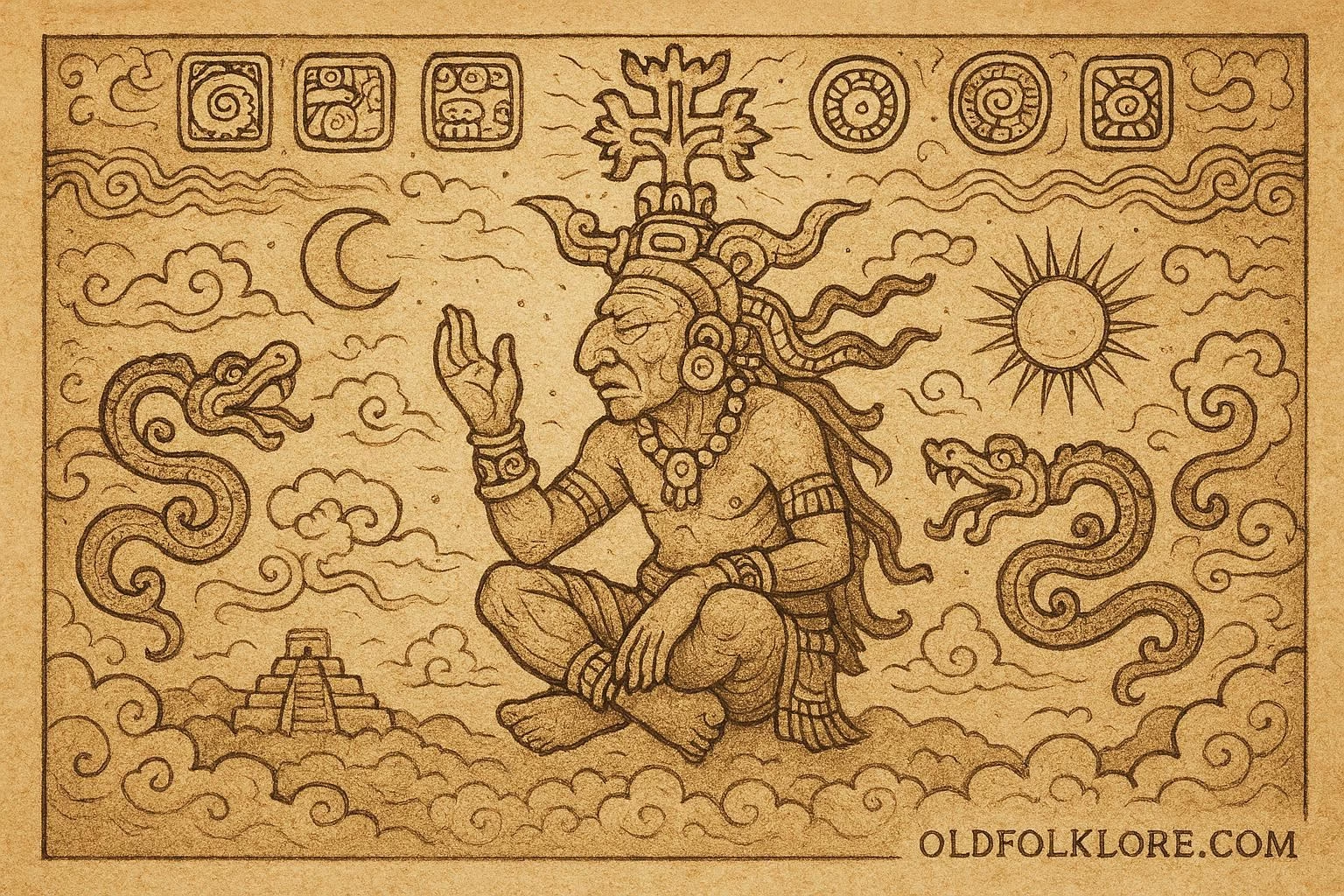

Itzamná stands among the highest deities of the ancient Maya, a supreme elder god of creation, knowledge, sky power, and sacred order. In Classic inscriptions, he appears as a dignified aged being, often toothless, long-nosed, and crowned with celestial symbols, embodying wisdom older than dynasties themselves.

He is the lord of writing, divination, calendrics, and cosmic authority, credited with teaching early humans the arts of glyphs, healing, and sacred governance. Maya rulers invoked him as a patron of kingship, for he was believed to write destinies across the heavens, inscribing divine will through stars, constellations, and cycles of time.

In codices and stelae he is sometimes paired with Ix Chel, the grandmotherly goddess of medicine and childbirth, forming a divine partnership associated with creation, fertility, and cosmic renewal. Itzamná is also closely linked to the Maize God, whose rebirth rituals mirror cosmic cycles that Itzamná oversees.

Sacred symbols associated with him include the sky band, the cross-shaped world-tree, serpents of divination, celestial glyphs, and the great bird aspect called Itzam Yeh, representing the heavens spread like wings across the world.

Mythic Story

The Sky House of Itzamná and the Writing of Creation

Long before cities rose in the forests of the Yucatán, before kings carved their names into stelae of stone, and before the first maize sprouted from the dark earth, the sky itself was a deep, unmarked silence. In that stillness sat Itzamná, ancient and eternal, dwelling in what the Maya called the “House of the Sky.” His form was like an elder sage, gentle and contemplative, yet his presence stretched across all directions of the cosmos.

He sat upon a throne woven of clouds and celestial serpents, gazing out over the primordial sea. From his brow shimmered the signs of time; from his fingers flowed the essence of knowledge. And in his hands he held a bundle of glyphs, unwritten, unnamed, awaiting the moment creation would begin.

Itzamná leaned forward, and the heavens stirred.

With a breath, soft as morning mist yet heavy with command, he unfolded the sky into four corners and four directions, raising the first world-tree whose branches would hold the pathways of gods and ancestors. As the trunk rooted itself in the deep waters below, the canopy burst into stars. The heavens gained shape, rhythm, and meaning.

Then, with slow, deliberate movement, Itzamná opened the bundle of glyphs. One by one he pressed them into existence. Each glyph became a force, a cycle, a principle: days, winds, rains, seeds, journeys, births. The codices later remembered this moment, saying: “Itzamná writes the fates in the skies.”

When the sky was set upon its pillars, Itzamná turned to the waters below. The sea rippled with anticipation, for it knew he carried the power to call forth life. He whispered a glyph, and from the surface rose the first land, pushed upward by sacred serpents. Mountains formed like the backs of ancient beings; valleys opened like resting places for future crops.

Yet creation was not complete.

As the land settled, Itzamná summoned two companions: the radiant goddess Ix Chel, with her jar of healing waters, and the youthful Maize God, whose presence brought promise of sustenance. Together they circled the new world, blessing soil, marking seasons, and preparing it for the beings yet to come.

When all was ready, Itzamná descended from the sky to walk upon the earth for the first time. The ground trembled under his gentle steps, not in fear but in reverence. He knelt beside a patch of fertile soil and breathed upon it. From that breath came the first humans, curious, bright-eyed, formed of maize and divine essence.

But humanity was unlearned, and the world still new. So Itzamná gathered his people beneath the world-tree and began to teach.

He taught them writing, tracing glyphs into bark paper so they could remember the movements of stars and the turning of seasons. He taught healing, guiding their hands to the plants Ix Chel blessed. He taught kingship, explaining that rulers must walk the path between heaven and earth, mirroring the balance he placed in the cosmos. And he taught divination, showing them that destiny is not fixed but read in the patterns the gods reveal.

As generations passed, kings rose who bore his teachings. They climbed pyramids shaped like mountains of creation and raised stelae carved with the glyphs he gave them. And whenever they performed rituals, they lifted their faces to the sky, knowing Itzamná watched from above, continuing to write their fates among the stars.

The Dresden Codex preserves an image of him seated in heaven, aged and serene, ink flowing from his hands like streams of divine thought. Even when storms gathered or kingdoms fell, the Maya believed Itzamná remained constant: the elder sky lord, keeper of wisdom, author of time.

And so his story endures, not as a single tale, but as the quiet thread woven through all Maya sacred knowledge. For wherever glyphs speak, wherever stars are read, wherever maize rises from dark soil, there the presence of Itzamná still lingers.

Author’s Note

The story of Itzamná reveals a deity who rules not through force, but through knowledge, balance, and sacred responsibility. His teachings mirror Maya values: the harmony of sky and earth, the duty of rulers to uphold cosmic order, and the belief that wisdom is a divine inheritance. Through him we glimpse a worldview where creation is written, learned, and lived, a universe shaped by understanding rather than domination.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What is Itzamná primarily associated with in Maya mythology?

A: Creation, writing, calendrics, wisdom, and sky authority.

Q2: Which goddess is commonly linked with Itzamná?

A: Ix Chel, deity of healing, childbirth, and lunar power.

Q3: What major sources depict Itzamná?

A: The Dresden Codex and Classic Maya inscriptions.

Q4: How does Itzamná create the world in mythic tradition?

A: By raising the sky, establishing world directions, forming land, and inscribing cosmic cycles.

Q5: What symbolism connects Itzamná to kingship?

A: He teaches rulers writing, sacred governance, and the reading of fate.

Q6: What creature or form represents his celestial aspect?

A: The great bird Itzam Yeh, symbol of the heavens.

Source: Maya Mythology (Dresden Codex & Classic inscriptions), Mesoamerica.

Origin: Maya Civilization, Mesoamerica (Classic Period)