The Zulu chief sat motionless on his seat of honor, his eyes fixed on the distant horizon where the land met sky. Day after day, he gazed toward the Cliffs of the Falling Goats, his heart heavy with grief that seemed to have no end. Seven of his sons, strong young men in the prime of their lives had ventured beyond those treacherous cliffs to prove their manhood, as tradition demanded. None had returned. The land beyond was known to be the domain of cannibals, and the chief feared the worst.

Only one son remained: his youngest boy. Though the young man was strong of body and bright of eye, showing every sign of intelligence and courage, he had never spoken a single word. From birth until now, no sound had ever passed his lips. The entire village had never heard his voice, and many wondered if he ever would speak.

Click to read all Myths & Legends – timeless stories of creation, fate, and the divine across every culture and continent

Old Mbata, the wisest induna or councillor in all the land, had served the chief faithfully for decades. He watched his lord’s suffering with deep concern, searching for any way to bring light back into those sorrow-filled eyes. Mbata observed, waited, and listened with the patience of the truly wise.

Then one morning, Mbata approached the grieving chief with urgent news.

“Nkosi, Lord,” he said, using the respectful title, “your youngest son has been trying to tell me something. Early each morning, he pulls at my arm and points toward the mountains where his brothers went. Each time, my old legs have moved too slowly, and by the time I arrived at the place he indicated, there was nothing to see.” Mbata paused, his weathered face thoughtful. “But today, I finally saw what had excited him: seven birds perched on the fence of the cattle kraal.”

The chief looked up with mild interest. “What is so strange about birds?”

“These birds were like no others I have ever seen,” Mbata explained, his voice filled with wonder. “They were bright green with waving plumes that caught the light like emeralds. They seemed completely unafraid when your son was near them, but the moment I drew closer, they took flight. Then they did something most peculiar they circled around my head three times before flying off toward the Cliffs of the Falling Goats.” The old induna’s eyes gleamed with certainty. “It would seem to me that they are magic birds.”

For the first time in many days, the chief’s eyes brightened with something like hope. “Have they come to comfort me for the loss of my sons?” He sat forward eagerly. “If that should be so, then I will reward you with seven of my fattest cattle. These magic birds must be caught. Send seven boys after them tomorrow. Surely they will catch them.”

So seven boys were chosen from among the village youth, each one brave and swift. The chief’s youngest son made it clear through urgent gestures and determined expressions that he insisted on being one of the seven. Though Mbata worried deeply about risking the life of the chief’s only remaining son, he understood that the boy needed to prove his own bravery, just as his brothers had. This was the path to manhood.

“Go and find these birds,” the chief commanded the seven young men. “Do not let me see your faces again until you return with them.” He handed each boy a sharp assegai a traditional spear. To his own son, he gave his personal assegai, a weapon of exceptional quality and power.

The next morning arrived with the soft colors of dawn, and sure enough, the strange green birds appeared once more. The chief watched from his kraal, with Mbata standing loyally at his side, as the seven boys followed the seven birds across the veld and gradually disappeared from sight.

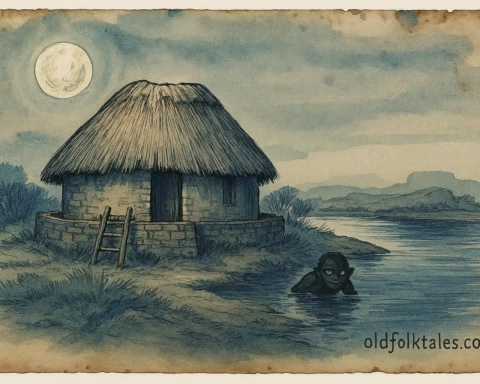

The beautiful birds led them far into wild bush country, past the ominous Cliffs of the Falling Goats, and over a great river that rushed and tumbled over ancient stones. There, the boys paused to gather twigs and rushes, weaving them into seven cages for the birds they hoped to capture.

The next morning, the birds led them up steep, forested mountains on the river’s far banks. The journey was exhausting, the terrain treacherous, but the boys pressed on. By the third evening, the birds began to beat their green wings more slowly. They were tired at last.

The chief’s son crept ahead of the other boys, moving with the silent skill of a practiced hunter. He made his way toward one of the birds perched on a thorn bush, barely breathing. Then, with perfect timing, he sprang forward and grabbed the long, shining tail feathers just as the exhausted bird tried to flutter beyond his reach.

Seeing his success, each of the other boys stalked and caught a bird for himself. When they gathered together beside their cages, they were all chattering with excitement about their victory.

“At last, at last!” the chief’s son suddenly shouted joyfully.

The other boys fell silent, staring at him in amazement. The boy who had never spoken had found his voice!

They rejoiced greatly with him, celebrating this miracle. Following Zulu tradition, they gave him a new name to mark this transformation, calling him Kulume, which means “speak.”

“Our task is won!” Kulume cried, his new voice ringing with happiness. “Tomorrow we can take our birds and my new voice back to my father. Let us start back toward home at once.”

They hurried down the mountain slopes, but darkness fell quickly in the forest. Soon they were stumbling through unfamiliar territory, clutching their precious cages. Then Kulume spotted the flickering light of a fire through the trees. He led them cautiously toward it but found no one there only an empty hut standing in the clearing. The place seemed safe enough, so exhausted, they lay down inside and fell asleep.

In the middle of the night, Kulume woke. The fire had died to ashes and the hut was pitch black. Then he heard a voice muttering nearby: “The meat smells good. I shall call my brothers!”

Terror seized Kulume’s heart they were in a cannibal’s hut.

He woke his friends silently, urgently, and led them far and fast through the darkness, their hearts pounding. But as the stars faded and morning light crept through the trees, Kulume realized with horror that in his haste, he had left his caged bird behind.

“We must all go back together,” one boy suggested, though all of them trembled with fear.

“No,” said Kulume firmly. “It is my fault. I must go alone. Don’t worry, I’ll be back.”

“But what will happen if we lose the chief’s last son?” wailed the other six boys.

“Watch my spear,” Kulume said, planting his assegai firmly in the ground. “If it stands still, I am safe. If it shakes, you will know I am in danger. If it falls, I am dead.”

He ran back into the forest before they could protest further. The sun climbed high in the sky. The six boys watched the spear with anxious eyes. Suddenly it trembled, then steadied itself. It trembled again, bent low, before steadying a third time. It shook violently and almost fell, then stood still once more.

As they breathed a collective sigh of relief, there was Kulume beside them, the cage and bird safely in his hand.

“What happened?” they cried.

Breathlessly, Kulume told them his tale. He had met an old woman fetching water beside a waterfall. Her pot was heavy, so he had stopped to help her carry it.

“Where are you going so fast?” she had asked, and he told her everything.

“You are brave,” she chuckled, and gave him some meaty fat in a little wooden bowl, along with whispered instructions.

When he reached the cannibals’ camp, he was horrified to see four of them rejoicing over something—or someone—roasting over their fire. He slipped inside the hut, found the little cage, and the bird warbled softly, as if glad to see him. But as he tried to escape, the cannibals spotted him in the firelight.

Quickly, following the old woman’s instructions, he rubbed some of the meat fat on a stone. When the cannibals rushed up, each one wanted the stone. One shouted, “It is mine!” and swallowed it. Immediately, the others attacked and ate him in a frenzy. Then they resumed chasing Kulume.

Twice more, as they caught up with him, he did the same thing, leaving the cannibals quarreling and feasting behind him in a horrible manner.

“So that is why your assegai trembled those three times,” exclaimed one of the boys.

“But you said there were four cannibals,” worried another. “If they stopped three times to eat one of their own, there must still be one left alive.”

At that very moment, the remaining cannibal sprang into the clearing with a bloodthirsty roar. He was huge and hairy and horrible. But he was heavy with all he had eaten, and no match for seven boys with seven sharp assegais. It was Kulume’s own blade that struck the killing blow.

For seven long days, the chief had sat gazing into the distance toward the Cliffs of the Falling Goats where his last son had ventured. The sun was gathering red clouds around it when he heard a shout from Mbata.

“I see seven figures, Nkosi, and they come running!” the old induna said, joy flooding his voice.

Across the valley came a clear cry: “It is I, your youngest son Kulume, who speaks with a new name! We bring the seven beautiful birds and, what is more, I bring my voice!”

The chief’s kraal filled with shouting and laughter as all his people rushed out to greet the boys. The noise stilled with wonder as they saw each boy standing behind his bird cage, arranged in a line across the path. Kulume bowed politely to his father, then ran along the line, cutting open each cage with his assegai.

From each cage arose not a bird, but a tall young man. The seven lost sons had come to life again.

That night, the valley was loud with rejoicing, and the chief’s long sorrow was turned to boundless joy.

The Moral Lesson

This powerful Zulu legend teaches us that true courage often means facing our fears alone, that the greatest transformations come through trials, and that seemingly impossible situations can have miraculous resolutions. Kulume’s journey shows that finding one’s voice both literally and metaphorically requires venturing into dangerous territory and confronting what frightens us most. The story also emphasizes the values of persistence, cleverness over brute strength, kindness to strangers (as shown when Kulume helped the old woman), and the belief that love can break even the darkest enchantments. Sometimes what appears to be lost forever can be restored through bravery and determination.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Kulume and why is he important in this Zulu legend? A: Kulume is the youngest son of a Zulu chief who had never spoken a word until he caught one of the seven magic birds. His name means “speak” in Zulu, given to him after he miraculously found his voice during the quest. He is the hero who not only gained the ability to speak but also freed his seven brothers from enchantment and defeated the cannibals.

Q2: What do the seven magic birds symbolize in this South African tale? A: The seven magic birds represent the chief’s seven lost sons who had been enchanted or transformed. They were bright green with waving plumes and appeared unafraid only around the youngest son. When Kulume cut open the bird cages at the story’s end, each bird transformed back into one of the lost brothers, revealing they had been under a magical spell.

Q3: What role does the wise induna Mbata play in the story? A: Mbata serves as the chief’s trusted councillor (induna) who observes the youngest son’s attempts to communicate about the birds and helps interpret the signs. He convinces the chief to send the boys on the quest and understands that the youngest son needs to prove his manhood despite the risks, showing wisdom about both practical matters and deeper spiritual understanding.

Q4: How did Kulume defeat the four cannibals? A: Kulume received help from an old woman he kindly assisted at a waterfall. She gave him magical meat fat in a wooden bowl. When the cannibals chased him, he rubbed the fat on stones three times. Each time, the cannibals fought over the stone, and one would swallow it, causing the others to attack and eat him. This happened three times until only one cannibal remained, whom Kulume and the other boys killed with their assegais.

Q5: What is the cultural significance of the assegai in this Zulu legend? A: The assegai (traditional Zulu spear) represents manhood, warrior status, and paternal blessing in Zulu culture. The chief giving his personal assegai to his youngest son symbolizes trust and the passing of responsibility. The assegai also serves as a magical indicator of Kulume’s safety standing still when he was safe, shaking when in danger, and threatening to fall if he faced death.

Q6: What does the journey beyond the Cliffs of the Falling Goats represent? A: The journey beyond the Cliffs of the Falling Goats represents the passage into manhood through trials and dangers. This treacherous place where cannibals lived symbolizes the threshold between childhood safety and adult responsibility. All the chief’s sons had to venture beyond it to prove their manhood, making it a rite of passage location in the story’s cultural context.

Source: Adapted from “South African Myths and Legends” told by Jay Heale

Cultural Origin: Zulu Nation, South Africa