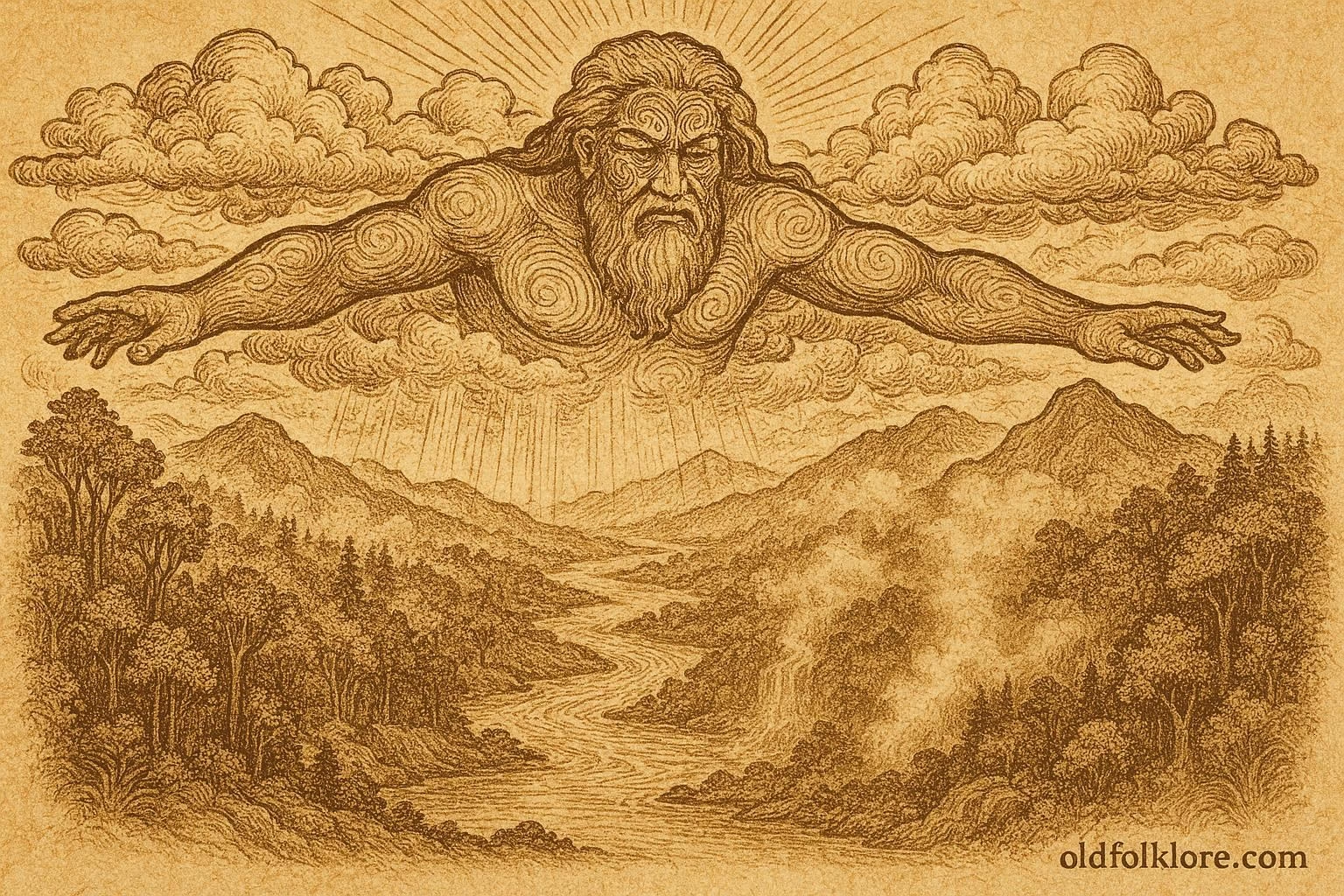

Ranginui, often called Rangi, is the primal Sky Father in Māori cosmology. He, along with Papa (Earth Mother), embodies the original union from which all life and existence flow. Their eternal embrace covers the world in darkness until their children, gods of various domains, intervene.

Ranginui’s domain is the sky itself; he represents the vastness above and the source of life-giving rains and mists. His role as progenitor links him to fertility, weather, and cosmic order. Ranginui is inseparable from Papa, the Earth Mother, highlighting the Māori conception of interconnectedness between sky, earth, and humanity. Symbolically, the tears of Rangi, which fall as rain, underscore the intimate emotion present even in divine beings, connecting natural phenomena to mythic narrative.

In Māori tradition, Ranginui is revered indirectly through acknowledgment of his children’s deeds and through the natural cycles of weather, sky, and the movement of celestial bodies. Certain iwi recount rituals to honor his generative role, and oral narratives convey the moral and cosmological lessons embedded in his story.

Mythic Story

In the beginning, Ranginui and Papa were tightly embraced, enveloping the cosmos in darkness. Their children, trapped between their parents’ loving yet confining forms, felt the need for light, air, and space to flourish. Among these children, Tāne, god of forests and birds, took the lead. He resolved to separate his parents, knowing that the freedom of the world and the creation of life as we know it, depended upon this act.

Tāne approached his father and mother, positioning himself between them. With great strength, he pushed upwards, pressing against Ranginui’s chest and lowering Papa to the earth. Slowly, inch by inch, the darkness lifted. The sky was raised, and light entered the world for the first time. This separation, while necessary, was not without sorrow. Ranginui cried at the loss of his close embrace, and his tears fell as rain upon the earth. The mists rising from the valleys and rivers became a living testament to his grief, an eternal reminder of the balance between creation and loss.

Each of Rangi and Papa’s children claimed their domains. Tangaroa, god of the sea, claimed the oceans; Tāwhirimātea, god of winds and storms, took the air currents; Tūmatauenga, god of war, claimed dominion over humans; Rongo became associated with cultivated food and agriculture. Tāne, having accomplished the separation, filled the forests with birds, insects, and trees, bringing life and abundance to the newly illuminated world.

Ranginui’s mourning, however, continued. Even as light spread and life flourished, he remained in constant sorrow. The rain, his tears, nurtured the earth and reminded his children of the love that once bound them all together. These tears became a vital part of the natural cycle: rivers swelled, crops were watered, and forests thrived. The Māori saw in this divine emotion a lesson of interconnectedness: grief and joy, creation and separation, are woven together in the fabric of life.

This foundational narrative also explains the structure of the cosmos in Māori thought. The sky above is Ranginui, the earth below is Papa, and between them, humans and other beings dwell. Their children, gods of forests, seas, and winds, maintain the order of the natural and spiritual worlds. The story teaches that while change and separation can bring light and life, it is always accompanied by remembrance, respect, and reverence for the sources of creation.

The separation of Rangi and Papa is not merely a historical myth but a living metaphor. It reflects human experience: the need for growth, space, and independence alongside love, loyalty, and the memory of unity. Every rainstorm, every cloud passing overhead, carries the memory of Rangi’s tears, a tangible expression of emotion in the natural world. Through this, Māori cosmology teaches that even divine beings are subject to the complexities of emotion, and that the natural world itself is alive with stories, lessons, and spiritual resonance.

Ranginui’s presence is thus felt not only in the sky but in every cloud, every rainfall, and every interaction between the heavens and the earth. His myth is both intimate and vast, connecting human life, the environment, and cosmic order in a single narrative thread. The world as Māori people know it, light, life, and the intricate balance of nature, exists because of the sorrow, love, and enduring presence of Ranginui.

Author’s Note

Ranginui’s myth illuminates the delicate interplay between love, loss, and creation. By separating from Papa, he allows life and light to flourish, teaching that growth often requires courage and sacrifice. His tears, essential to the natural cycles, remind humanity that grief is not separate from life’s abundance but sustains and nourishes it. Through Ranginui, Māori cosmology illustrates the interconnectedness of all beings and the sacred rhythms of the cosmos.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Ranginui?

A: Ranginui is the Sky Father in Māori mythology, representing the sky and the source of life-giving rain.

Q2: What prompted Tāne to separate Ranginui and Papa?

A: Their children needed light, air, and space to flourish; the world was dark and confined between their embrace.

Q3: What natural phenomenon represents Ranginui’s grief?

A: Rain and mists are his tears.

Q4: Which deity claimed the domain of the oceans?

A: Tangaroa, god of the sea.

Q5: How does the story explain the Māori cosmos?

A: Ranginui is the sky, Papa the earth, and their children govern the natural and spiritual domains in between.

Q6: What lesson does Ranginui’s story convey about life?

A: Growth and creation may require separation or change, but love, memory, and respect remain essential.

Source: Māori Oral Traditions, New Zealand (White, 1887).

Source Origin: Māori, New Zealand