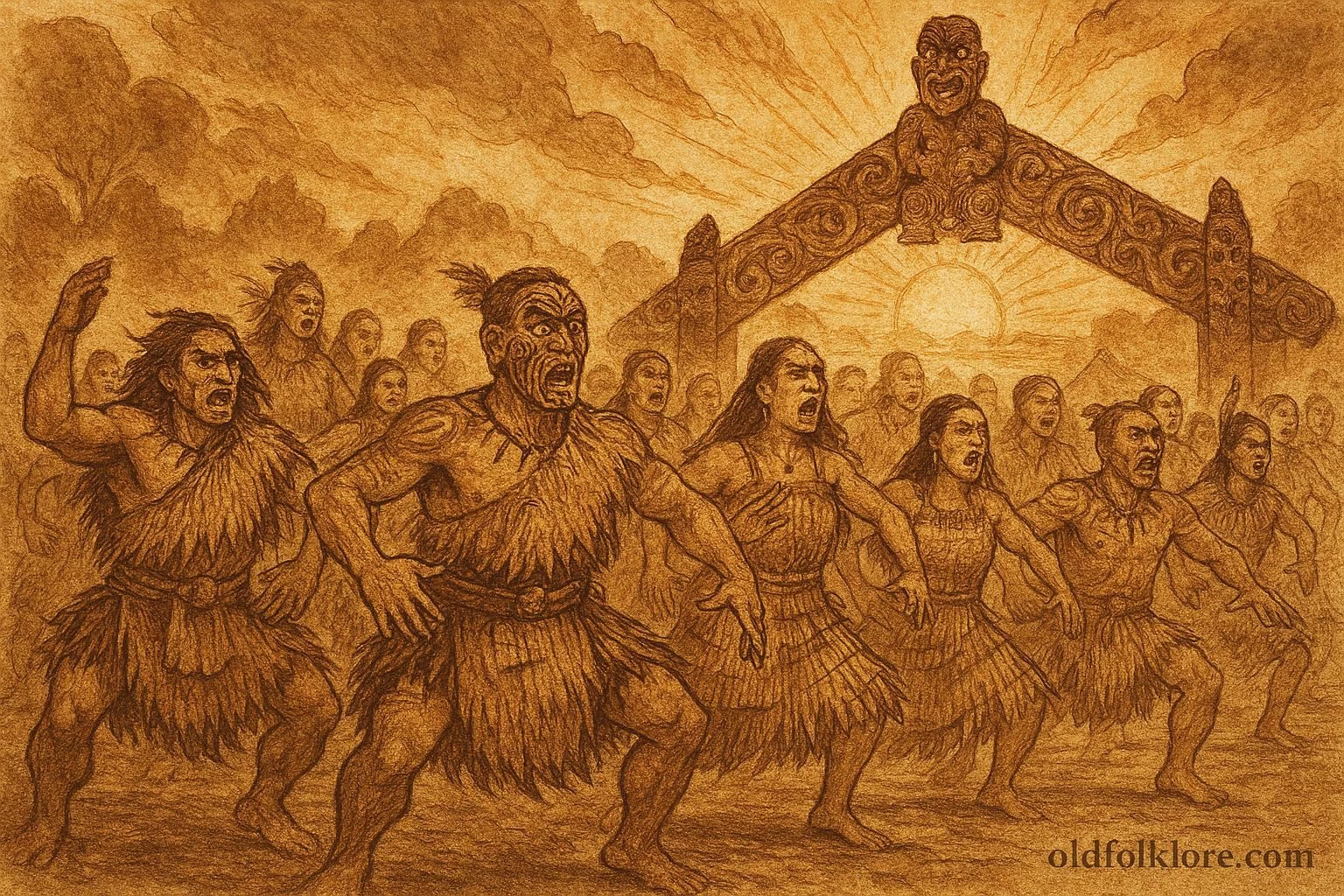

The haka is one of the most profound ceremonial expressions of the Māori people, an Indigenous Polynesian culture rooted in Aotearoa. Although globally recognized today, haka is far older than modern performance contexts. Its origins reach into the mythic realm, where the gods themselves first shaped its movements. Māori oral tradition teaches that haka was born from Tāne-rore, the son of Hine-raumati (the Summer Maid) and Tama-nui-te-rā (the Sun). The shimmering air on hot days, known as the “trembling of Tāne-rore’s hands”, is considered the first haka ever performed.

From this divine beginning, haka evolved into a rich ceremonial language expressing identity, challenge, mourning, welcome, and communal memory. Each iwi (tribe) developed its own haka, embodying historical events, genealogies, victories, laments, and displays of mana.

Description

To understand haka, one must see it not as a dance but as an embodied declaration of existence. Māori communities long recognized the body as a vessel of ancestral power, an instrument through which memory, genealogy, and divine presence can be expressed. Haka allows a group to unite their breath, rhythm, and intention so fully that they become a single voice.

Historically, haka was performed for several purposes. Haka peruperu, the fierce war haka, prepared warriors spiritually before battle. Featuring high leaps, vigorous stamping, and weapon displays, it infused the group with courage while unsettling the enemy. A misstep in its synchronized movements was believed to be a bad omen.

Haka pōwhiri appeared during welcoming ceremonies on the marae, the communal courtyard, where hosts affirmed their identity and honored visitors. In funerary contexts, haka tangi expressed communal grief, love for the departed, and the enduring bond of whakapapa (genealogy). Even joyful events such as births, weddings, and achievements could call for haka akoako, a celebratory form that praised the moment and strengthened unity.

Throughout all these variations, the structure remained consistent: chanting or sung recitation, coordinated body movements, and symbolic gestures. Performers stamped the ground to awaken ancestral presence, slapped their chests to embody strength, rolled their eyes to invoke intensity, and protruded their tongues to display defiance in war contexts. Every movement carried meaning, and every meaning was tied to history.

The words of a haka were just as important as the movements. Composed by knowledgeable tribal historians or revered leaders, haka texts preserved accounts of migrations, battles, alliances, mythical origins, and moral principles. Many were considered tapu (sacred), requiring respect, precision, and emotional truth.

Despite colonization, suppression of Indigenous practices, and cultural pressure, haka never disappeared. Instead, it transformed and endured. When Māori regiments performed haka during World Wars, they reignited ancestral pride. When schools, communities, and families revived the practice during the twentieth century, haka became a symbol of resistance and resurgence.

Today, haka remains central to Māori life. It is performed at funerals, birthdays, graduations, tribal gatherings, and national ceremonies. Its prominence in sporting events—most famously the All Blacks’ haka “Ka Mate”, has brought it global recognition, but haka’s essence remains profoundly Māori. It is a living language of spiritual intent, a ritual that reminds people of who they are and who stands behind them.

Mythic Connection

At its root, haka is a dialogue with the divine. The trembling movement of Tāne-rore is reflected in the quiver of performers’ hands. The stamping of feet echoes the pulse of Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother. The haka’s collective breath, synchronized and forceful, symbolizes the shared life-force known as hau. By performing haka, Māori invoke the spiritual energy of mana, the sacred authority inherited from ancestors and bestowed by the gods.

Connection to the divine appears in more than the movements. The communal nature of haka reflects the Māori worldview that life is woven through interconnected genealogies. No performer stands alone; each carries the strength of their lineage. Through haka, ancestors are honored, invoked, and made present.

Thus, haka is not simply a performance. It is a sacred act that moves between worlds, joining the living with the unseen and renewing the spiritual bonds that sustain Māori identity.

Author’s Note

This article explores the haka as a sacred Māori expression of communal memory, divine ancestry, and spiritual unity. It highlights how movement, voice, and mythic symbolism combine to create a ritual that strengthens identity and ties the present to the ancestral past.

Knowledge Check

1. Who is considered the mythic origin of haka?

Tāne-rore, whose trembling represents the first haka.

2. What does stamping the ground symbolize?

A connection to Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother.

3. What is haka peruperu?

A war haka performed before battle to invoke courage and unity.

4. Why are haka texts important?

They record tribal history, migration stories, and ancestral memory.

5. How is haka used in funerary rituals?

It expresses grief, honors the dead, and strengthens communal bonds.

6. Why is haka still significant today?

It preserves Māori identity, rituals, and ancestral power in modern life.