Mwaka Kogwa is a New Year ceremony practiced primarily in Makunduchi, on the southern coast of Zanzibar. Rooted in a blend of Shirazi-Persian heritage and Swahili coastal traditions, it marks the start of the solar year known locally as Nowruz ya Kiunguja. The ritual’s foundations trace back to early Persian settlers who brought agricultural New Year customs centered on renewal, fire cleansing, and the symbolic release of misfortune. Over centuries, these practices merged with African coastal spiritual customs, creating a uniquely Swahili ceremony that blends ancestral reverence, community healing, and seasonal transition. Mwaka Kogwa symbolizes not only the beginning of the year but also the emotional and spiritual rebalancing of society.

Description

The heart of Mwaka Kogwa lies in ritualized conflict, symbolic destruction, and communal reconciliation. The ceremony begins with two kin-based neighborhoods taking part in mock battles. These playful fights are conducted with banana stalks instead of weapons, ensuring that the conflict is symbolic rather than harmful. The event allows old grievances, suppressed frustrations, social tensions, and personal disagreements, to be released in a culturally sanctioned performance. By striking the banana stalks against one another, participants “break open” the year’s misfortune, transforming private resentments into harmless public spectacle.

Women support the ritual through celebratory songs and dance. Their performances reinforce joy, unity, and communal blessing. The songs, many of them ancient, invoke themes of fertility, protection, and prosperity. Through rhythm, humor, and poetic language, the women reinforce the message that life must move forward with laughter rather than bitterness.

After the mock conflicts, the community gathers around a carefully prepared structure of woven grass and reeds. The effigy represents the old year, everything unwanted, unspoken, or unresolved. When the structure is set ablaze, flames roar upward, carrying misfortune away. Fire, in both Persian and Swahili cosmology, serves as purifier, destroyer, and messenger. As smoke rises, elders observe the direction of the wind and the intensity of the flames. These natural signs are interpreted as omens for agricultural success and social well-being in the coming year.

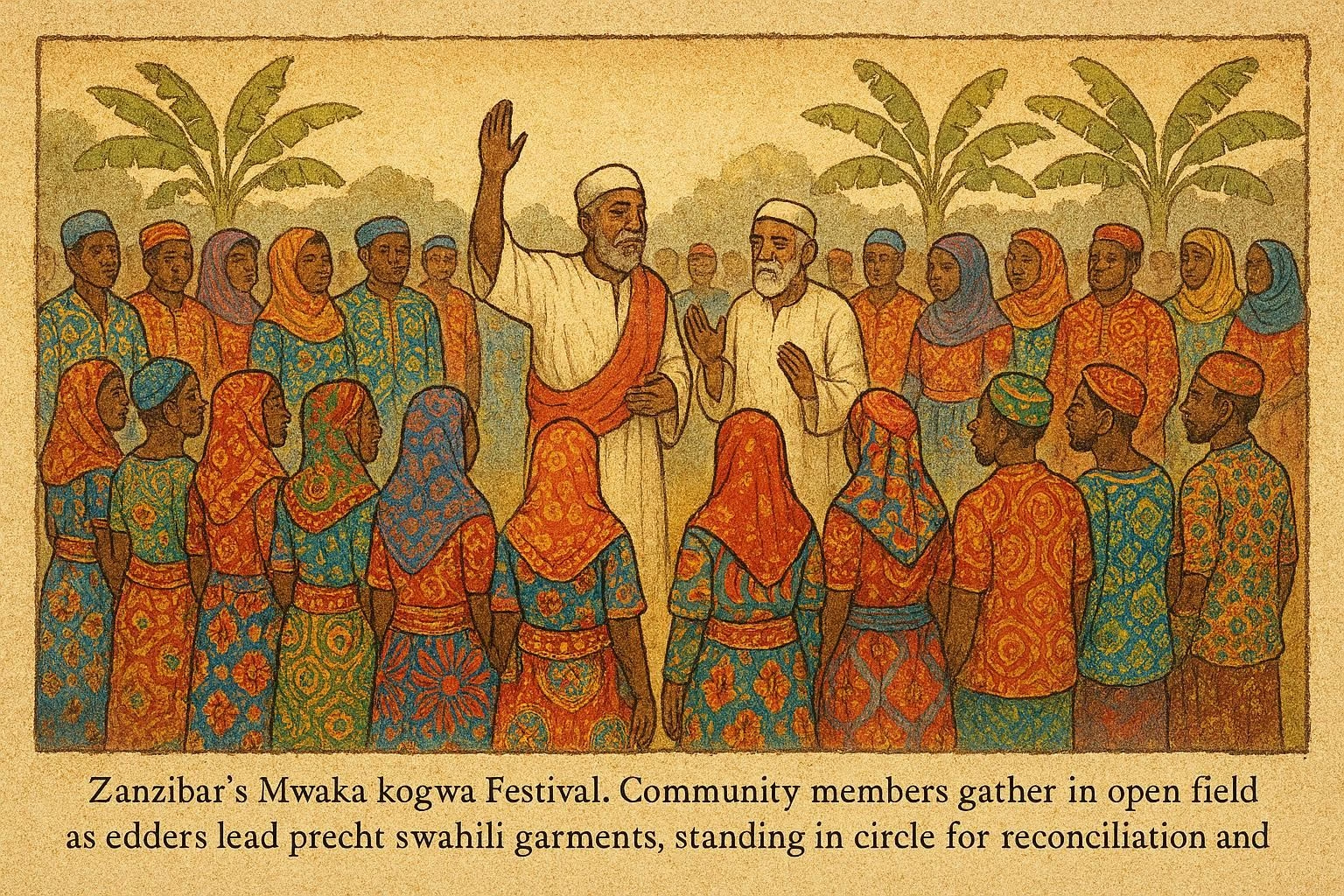

Once the flames die down, the mood shifts. Reconciliation becomes the focus. Elders, clan leaders, and family representatives engage in blessings, apologies, and ceremonial handshakes. People who have held private disagreements are encouraged to acknowledge them and release them. The event culminates with feasting, platters of rice, coconut dishes, and meats shared widely among neighbors. Food bridges families, resets relationships, and reaffirms community identity.

Modern tourism has added new layers of spectacle, but the core meaning of Mwaka Kogwa remains firmly intact. Despite public performances and international visitors, local households continue to treat the ritual as essential to maintaining peace, good fortune, and ancestral protection. In Makunduchi, many families insist that without Mwaka Kogwa, the year cannot truly begin.

Mythic Connection

Though Mwaka Kogwa does not revolve around a single deity, its symbolism aligns with ancient cosmological principles shared across the Indian Ocean world. The fire ritual reflects an older worldview in which flames cleanse the spiritual landscape, revealing a fresh path for the year ahead. This concept echoes the Persian Nowruz tradition, where fire absorbs misfortune and invites cosmic renewal. In Swahili spiritual belief, fire is also associated with ancestral presence, transformation, and the removal of lurking spirits that bring disease or conflict.

The mock battles represent a deeper mythic idea: the world must pass through symbolic chaos before returning to balance. By enacting disorder safely and publicly, the community reaffirms its connection to a larger cosmic cycle. Conflict becomes a controlled ritual instead of a social rupture.

Women’s songs highlight the connection to fertility and protection. These themes relate to Mwezi, the moon, whose cycles shape coastal agriculture, tides, and spiritual rhythms. The lunar influence on the ritual underscores the Swahili belief that the natural world and human society move in parallel patterns.

The reconciliation phase echoes the idea that the ancestors watch over the community’s moral conduct. One must enter the New Year with a clean heart to maintain the blessings of those who came before. Thus, Mwaka Kogwa is not simply a festival, it is a spiritual reset grounded in fire, nature, and ancestral harmony.

Author’s Note

This article examines Mwaka Kogwa as a ritual of renewal shaped by Swahili and Shirazi heritage. It highlights the ceremony’s symbolic conflict, fire cleansing, and reconciliation practices, showcasing how the ritual preserves ancestral values and restores communal harmony in Zanzibar.

Knowledge Check

1. What is the main purpose of Mwaka Kogwa?

To mark the New Year through symbolic conflict, fire cleansing, and community reconciliation.

2. Why are banana stalks used in the mock battles?

They allow symbolic conflict without harm, releasing tension safely.

3. What does the burning effigy represent?

It symbolizes the old year’s misfortune, negative energy, and unresolved problems.

4. How do elders interpret the fire?

They watch flame patterns and wind direction as omens for the coming year.

5. Why are women’s songs important?

Their songs invoke fertility, joy, and community blessings, reinforcing social unity.

6. How does Mwaka Kogwa connect to nature?

It uses fire, wind, and seasonal observation to align human life with cosmic rhythms.