High upon Coatepec, the sacred Serpent Mountain, lived Coatlicue, the ancient goddess whose name meant “She of the Serpent Skirt.” She was a being of profound power and mystery, a mother goddess who had already given birth to hundreds of celestial children. Her daughter was Coyolxauhqui, the golden moon goddess whose face bore the painted bells of a warrior. Her four hundred sons were the Centzon Huitznahua, the stars of the southern sky, fierce and prideful warriors who moved across the heavens in glittering array.

Coatlicue lived a life of devotion and sacred duty. Each day, she would climb to the temple atop Coatepec to sweep and tend to the holy space, honoring the divine forces with her humble labor. She wore a skirt woven with serpents that writhed and hissed, and her devotion to the cosmic order was unwavering. Despite her divine nature, she performed these tasks with the quiet dignity of a woman who understood that even the gods must serve something greater than themselves.

One morning, as the first light painted the mountain peaks in shades of gold and crimson, something extraordinary occurred. As Coatlicue swept the temple grounds, a ball of brilliant feathers descended from the sky soft, shimmering plumes of hummingbird down that seemed to glow with an inner light. The feathers drifted down like snow, weightless and sacred, carrying with them a power beyond mortal understanding. Coatlicue, moved by their beauty and sensing their divine nature, carefully gathered the feathers and tucked them into her bosom, close to her heart.

In that instant, through that miraculous touch, Coatlicue became pregnant.

When her children discovered their mother’s condition, shock and outrage swept through them like wildfire across dry grass. Coyolxauhqui’s face flushed with shame and fury. The four hundred brothers gathered around their sister, their voices rising in a thunderous chorus of indignation. How could their mother, the great goddess, be pregnant without a husband? How could she bring such dishonor upon their family? They saw not a miracle but a scandal, not divine intervention but a stain upon their cosmic reputation.

“She has shamed us!” Coyolxauhqui cried, her bells jingling with rage. “She has brought disgrace to our name!”

The brothers echoed their sister’s fury, their voices blending into a terrible war cry that shook the foundations of Serpent Mountain. They painted their faces with the colors of death and battle. They took up their weapons obsidian-edged clubs, sharp spears, shields decorated with feathers and bone. Their anger transformed them into an army, four hundred strong, with Coyolxauhqui at their head, her golden face twisted with determination and wounded pride.

“We must kill her,” they decided. “We must restore our honor.”

As the warriors prepared for battle, readying themselves to march up Serpent Mountain to slay their own mother, Coatlicue learned of their plans. Terror gripped her heart. She stood alone at the summit, her hands pressed against her swollen belly, tears streaming down her ancient face. How could her own children turn against her? How could they not see the sacred nature of what was happening?

But from within her womb, a voice spoke strong, commanding, filled with the fire of the sun itself.

“Do not fear, my mother,” said the unborn child. “I know what must be done.”

The voice belonged to Huitzilopochtli, the Hummingbird of the South, the Left-Handed Hummingbird, the god who had not yet been born but who already possessed the wisdom and power of the cosmos itself.

Coyolxauhqui led the charge up the mountain. Her brothers followed in a massive wave of righteous fury, their war cries echoing off the cliffs, their weapons gleaming in the light of their sister, the moon. They climbed higher and higher, their feet pounding against stone, their hearts filled with the conviction that they were doing what was necessary, what was right.

At the base of the mountain, one brother faltered. His name was Cuahuitlícac, and doubt had crept into his heart. He could not shake the feeling that they were making a terrible mistake. As his siblings climbed, he ran ahead by a secret path and warned Coatlicue of their approach, telling her how close they were, how fierce their anger burned.

Each time he brought news, Huitzilopochtli’s voice would respond from within the womb, calm and assured: “Listen carefully. Tell me when they draw near.”

The army of stars and moon reached the summit. They stood before their mother, weapons raised, hearts hardened against mercy. Coyolxauhqui stepped forward, her golden face reflecting the dawn light, ready to deliver the fatal blow.

And in that precise moment, Coatlicue gave birth.

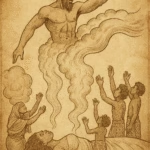

But this was no ordinary birth. Huitzilopochtli emerged not as a helpless infant but as a fully-grown warrior god, magnificent and terrible to behold. He burst forth clad in armor made of hummingbird feathers that shimmered blue and green like precious stones. His face was painted with the sacred stripes of war. In his left hand for he was the Left-Handed One he wielded the Xiuhcoatl, the Fire Serpent, a weapon of pure blazing energy that twisted and coiled like living flame.

The newborn god surveyed his siblings with eyes that burned like the sun itself.

Without hesitation, Huitzilopochtli attacked. The Fire Serpent struck like lightning. With one devastating blow, he struck down Coyolxauhqui, severing her head from her body. His strength was overwhelming, his fury righteous and terrible. He dismembered his sister completely, her golden limbs scattering, her body broken into pieces that tumbled down the steep sides of Coatepec, rolling and bouncing until she lay shattered at the mountain’s base.

Then Huitzilopochtli turned upon his four hundred brothers. Like the rising sun that scatters the stars, he pursued them across the sky. They fled in terror before his brilliance, these proud warriors who had thought themselves so powerful. The Centzon Huitznahua scattered to the four corners of the heavens, becoming the stars that flee before the dawn, forever running from their brother’s light.

The battle was complete. Huitzilopochtli stood victorious upon Serpent Mountain, his Fire Serpent blazing in his hand, his hummingbird feathers catching the first rays of morning. He had defended his mother’s honor and established his place in the cosmos. From that day forward, he became the sun itself, the great warrior who must fight his way across the sky each day.

And each night, as the sun sets and darkness falls, Coyolxauhqui rises as the moon, her dismembered body pieced back together in silver light. Her four hundred brothers appear as stars, scattered across the heavens. But when dawn approaches, when Huitzilopochtli begins his daily journey, they flee before him the eternal pursuit, the cosmic battle that has continued since that first violent birth upon Serpent Mountain.

The Mexica people remembered this story in their great temple in Tenochtitlan, where they built a pyramid to honor both Huitzilopochtli and his mother. They understood that the sun’s daily victory was not guaranteed, that it required strength and sacrifice, and that the cosmic order itself was born from conflict and defended by divine warriors.

Click to read all Myths & Legends – timeless stories of creation, fate, and the divine across every culture and continent

The Moral of the Story

The birth of Huitzilopochtli teaches profound lessons about divine purpose, cosmic balance, and the nature of honor. The story illustrates that rushing to judgment without understanding the full truth can lead to tragedy Coyolxauhqui and her brothers acted on perceived dishonor rather than recognizing the sacred miracle occurring before them. It also emphasizes the Aztec worldview that the universe requires constant struggle to maintain order; the sun must battle the moon and stars each day to bring light to the world.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who was Coatlicue and why did she become pregnant?

A: Coatlicue was an ancient Aztec mother goddess whose name means “She of the Serpent Skirt.” She became miraculously pregnant when she gathered a ball of beautiful feathers that descended from the sky while she was sweeping the temple on Serpent Mountain, tucking them close to her heart.

Q2: Why did Coyolxauhqui and her brothers attack their mother?

A: Coyolxauhqui, the moon goddess, and her four hundred brothers (the Centzon Huitznahua, representing the southern stars) believed their mother had brought dishonor to the family by becoming pregnant without a husband. They did not recognize the pregnancy as a sacred, miraculous event and decided to kill her to restore their honor.

Q3: What does the name Huitzilopochtli mean and what was unique about his birth?

A: Huitzilopochtli means “Hummingbird of the South” or “Left-Handed Hummingbird.” Unlike normal births, he emerged not as an infant but as a fully-grown, fully-armed warrior god, immediately ready for battle, wearing hummingbird feather armor and wielding the Xiuhcoatl (Fire Serpent) weapon.

Q4: What happened to Coyolxauhqui after the battle?

A: Huitzilopochtli struck down his sister Coyolxauhqui with his Fire Serpent weapon, beheading and dismembering her body, which then tumbled down Serpent Mountain. She became the moon, her fragmented form pieced back together each night in silver light, eternally pursued by her brother, the sun.

Q5: What cosmic symbolism does this myth explain?

A: The myth explains the daily celestial cycle: Huitzilopochtli represents the sun, Coyolxauhqui represents the moon, and the four hundred brothers represent the stars. Each day, the sun (Huitzilopochtli) rises and defeats the moon and stars, chasing them across the sky,a cosmic battle that repeats eternally, explaining day and night.

Q6: What cultural significance did this story hold for the Aztec/Mexica people?

A: This myth was central to Aztec religious beliefs and practices. It justified their emphasis on warfare and human sacrifice, as they believed they needed to nourish Huitzilopochtli with blood and hearts to give him strength to continue his daily battle across the sky. The great temple in Tenochtitlan was built to honor this story, with stairs representing Serpent Mountain where the cosmic battle occurred.

Source: Adapted from the Florentine Codex (Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España), Book 3, compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún (16th century).

Cultural Origin: Mexica/Aztec, Central Mexico