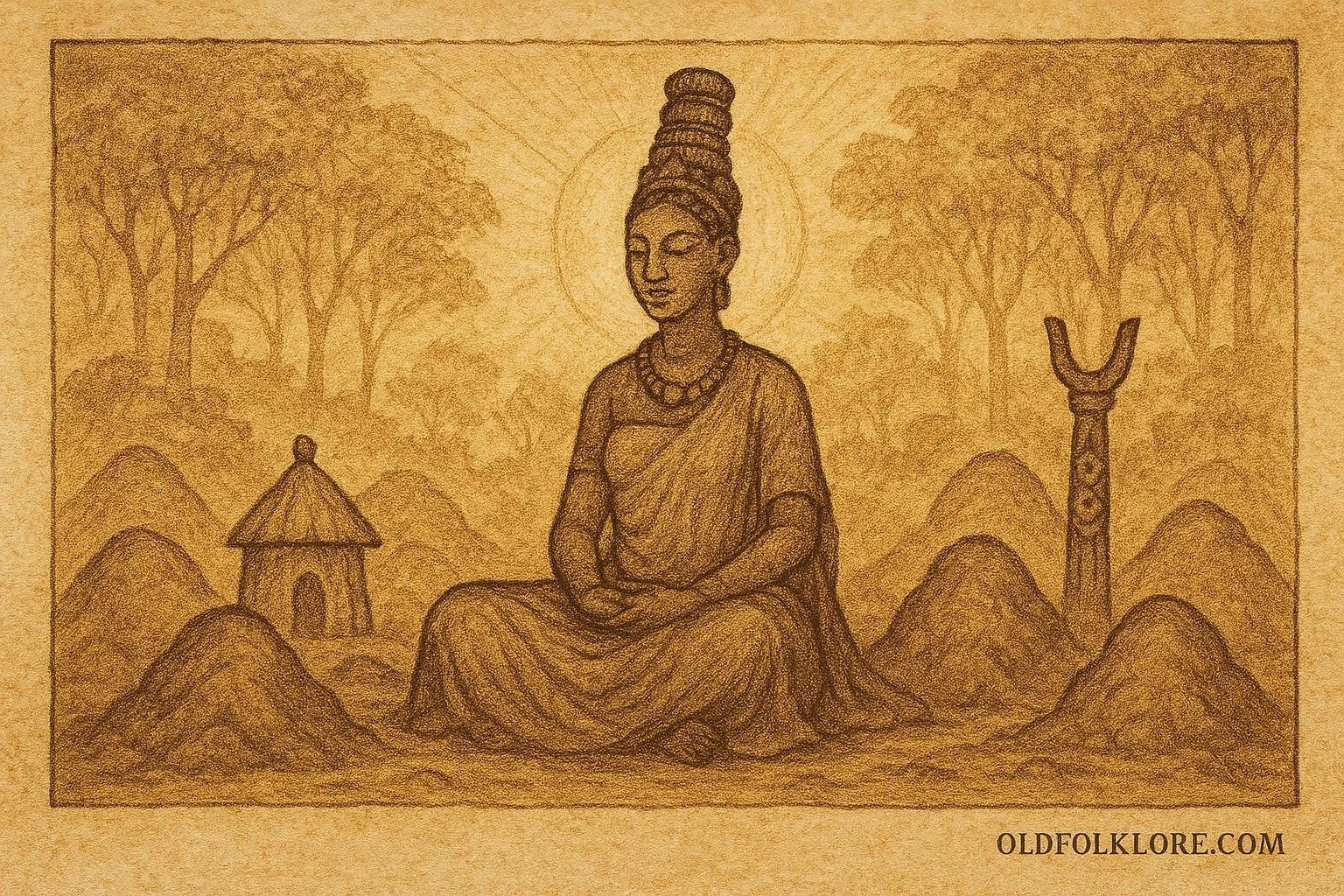

Al, also called Ani in many northern Igbo communities, is the revered Earth Mother, the embodiment of the land upon which all life grows, walks, and returns in death. She is the custodian of fertility, morality, ancestral resting places, and omenala, the Indigenous customary law that binds human conduct to cosmic balance. Every furrowed field, every burial ground, every hearth that draws its clay from the earth belongs to her.

As the spiritual foundation of Igbo communities, Ala governs nso Ala, the taboos that protect the moral order. Offenses against the Earth are considered the gravest transgressions, for, as older Igbo traditions say, “one lives and dies upon the body of Ala.” She is also intimately connected to lineage ancestors, who rest within her depths, and to agricultural cycles that depend on her blessing.

Her shrines, mound-like earth altars called aja ala, stand at the heart of villages, marking spaces where disputes are settled, oaths are sworn, and sacrifices are offered to repair breaches in moral and cosmic harmony. No major communal decision begins without acknowledging the Earth Mother, for she is both the witness and the enforcer of truth.

THE MYTHIC STORY: The Woman Who Broke Ala’s Earth Taboo

In the red-earth villages of old Igboland, the Week of Peace was a time when no quarrel was raised, no blood was spilled, and no act of impurity touched the soil. Fields rested. Tools slept in silence. Even the wind seemed to soften, moving carefully across yam mounds as though respecting an ancient pact. For during this sacred week, the Earth was not merely ground beneath the feet, she was Ala herself, vigilant, listening, and awake.

It is said that in one such village lived a woman named Nwamaka, respected for her fine harvests and steady character. Yet beneath her calm surface lay a burden she carried alone, a shame that grew heavier with each passing season. On the first day of the Week of Peace, before dawn broke fully across the ridges, she crept behind her compound wall carrying a small bundle wrapped in cloth. Its contents, an object considered spiritually unclean, were forbidden to be buried in the earth during sacred time. But Nwamaka, consumed by fear of public judgment, believed that burying it would conceal her wrongdoing forever.

The sky remained quiet as she knelt upon the cool soil. The ground was still damp from night mist, glistening as though watching her with a thousand tiny eyes. She hesitated, then pressed the forbidden object into the earth, covering it quickly with trembling hands.

When she stood, the world seemed unchanged. Birds called from thatched rooftops. Smoke rose lazily from cooking fires. No thunder split the sky. Nwamaka exhaled with relief. She believed she had hidden her secret.

But Ala had seen.

In the Igbo worldview, the Earth Mother is not blind soil; she is the living moral pulse of the land. To violate her body is to wound the harmony that binds community, ancestors, and the rhythms of life. Though Nwamaka returned to her home, the earth beneath her feet carried her offense like a bruise spreading slowly through the world.

At first the signs were subtle: yam vines drooped despite recent rain, and the cassava leaves curled as though touched by invisible heat. The village diviner cast cowries, seeking the cause, but the patterns formed were troubled, evasive. Then children fell sick with unusual fevers. A restless stillness settled over the goats and chickens. Even the elders whispered uneasily, sensing the shift.

By the third day, the village square was heavy with dread. The priest of Ala, a grey-bearded man whose staff bore the carvings of generations, declared that an abomination, nso Ala, had been committed. The Earth Mother had been offended, and until the culprit confessed, the land would continue to suffer.

Fear rippled through the people. None wished to stand against Ala; no one dared accuse another. So the priest led the villagers to the sacred grove, where ancient trees rose like pillars of an unseen temple. There, he called upon Ala with palm wine and chalk markings, pleading for a sign.

The wind stirred, low and slow, and the earth beneath the grove vibrated faintly, an unmistakable response. The priest’s voice grew stern:

“The one who has touched the Earth with impurity must step forward. Ala does not forget.”

Nwamaka felt her heart pound like a drum. Her knees weakened. The weight she had buried beneath the soil seemed to rise inside her chest. At last, trembling, she stepped forward and fell to her knees. Her confession spilled out like a breached calabash, fear, shame, and the desperate attempt to hide what could not be hidden from the Earth Mother.

The villagers listened in silence. There was no anger, only a collective grief that one among them had allowed fear to overshadow respect for the laws that bound them together.

The priest lifted Nwamaka to her feet and declared that Ala demanded purification, not destruction. The village prepared the rites: cleansing with sacred water, offerings of kola nut and a white hen, and public acknowledgment of the wrongdoing so that the moral fabric of the community could be rewoven.

When the rituals were completed, the earth was touched with chalk and blessed. That night the air shifted, carrying the cool scent of renewal. By morning the yam vines straightened, dew shimmering on their leaves. Children’s fevers broke. Goats bleated again in their pens.

Balance had been restored.

The people understood the lesson deeply: the Earth Mother protects, but she also remembers. To offend her is to endanger not only oneself but the entire community that lives upon her sacred body. And so the story of Nwamaka became a whisper passed from elder to child, a reminder that fear must never triumph over truth, and that no secret buried in the earth remains hidden from Ala.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This mythic episode reflects the core of Igbo cosmology: morality is not abstract but woven into the land itself. Through Ala, the Earth becomes a living judge whose concern extends beyond individual wrongdoing to the harmony of the entire community. The tale also reveals the compassionate dimension of Ala, balance restored not through vengeance, but through confession, reparations, and ritual reconciliation. The Earth Mother demands truth, but she also offers renewal.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What domains does Ala/Ani govern in Igbo belief?

A: Earth, fertility, morality, ancestors, and customary law (omenala).

Q2: What is nso Ala?

A: Moral-religious taboos whose violation offends the Earth Mother.

Q3: Why was the Week of Peace important?

A: It was a sacred period when the earth could not be defiled or disturbed.

Q4: What caused the village’s crops to wither in the myth?

A: Nwamaka’s burial of a forbidden object during the Week of Peace.

Q5: How was balance restored after the offense?

A: Through confession, communal purification rites, and offerings to Ala.

Q6: What does the story teach about Igbo morality?

A: Moral order is tied to the land, and wrongdoing affects the entire community.

Source: Igbo Mythology, Nigeria.

Source Origin: Igbo, Nigeria