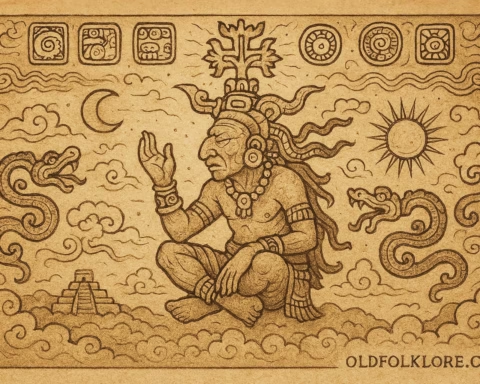

Chaac is the revered Maya god of rain, storms, lightning, and agricultural fertility, a deity whose presence determines the rhythm of life across the ancient Maya world. In a land where maize was not merely a crop but the very substance of human creation, the rains governed by Chaac meant survival, abundance, or hardship. He is often depicted with a serpent-like face, long curling nose, and fanged mouth, wielding his lightning axe, an instrument through which he strikes the clouds to release rain.

Maya tradition speaks not of a single Chaac but of four Chaacs, each aligned with a cardinal direction: Chac Xib Chaac (East), Sac Xib Chaac (North), Ek Xib Chaac (West), and Kan Xib Chaac (South). Each governs rainfall in their quadrant of the world, working together to maintain cosmic balance. Their colors, red, white, black, and yellow, mirror the sacred hues of maize kernels found across Maya cosmology.

Explore the shadows of world mythology, where demons test the soul and spirits watch over mankind

Chaac is closely intertwined with the serpent, a symbol that embodies both storms and fertility. Lightning itself is often imagined as the strike of a celestial serpent descending from the heavens. Temples, caves, cenotes (sacred water-filled sinkholes), and mountaintop shrines served as ritual sites where offerings were made to Chaac. During ceremonies, dancers wearing serpent masks, shells, and rattles invoked him, calling upon the rains to bless the fields.

Mythic Story

Long ago, when the Maya people were still learning the rhythm of seasons and winds, the skies above the world were restless. The land waited anxiously for the rains, rains that determined whether maize would thrive or wither. High in the celestial realms, Chaac watched over the earth, his great axe resting against storm-dark clouds, listening for the cries of those below who relied upon him.

One season, drought spread across the land. Rivers retreated into narrow channels. Cenotes grew shallow. The maize plants stood frozen in the fields, leaves curled like clenched fists yearning for water. The people gathered at temples, offering incense and prayers, hoping Chaac would hear.

In the eastern village of Tulan Zuyua, a group of elders consulted the sacred calendar. The signs revealed that the Four Chaacs were unbalanced; their harmony weakened by a quarrel among the cardinal spirits. Without unity, rain could not be released. The elders lit copal resin and sang to the heavens, pleading: “Chaac, Rainbringer, hear us. Restore balance so life may return.”

Their voices reached the divine realm, where Chaac stood upon a sky-mountain of thunderheads. He sensed the discord among his four aspects, forces meant to move in harmony like the cycle of seasons. East accused West of withholding rain. North blamed South for scattering storms. Lightning flickered between them in heated argument.

Chaac raised his axe, the blade glimmering with the blue-white brilliance of lightning. The quarrel ceased. His voice rolled like distant thunder.

“Brothers of the directions, remember that the world survives only by our shared breath. Without unity, there is no rain, no maize, no life.”

But the Four Chaacs struggled to agree, each believing his rains were most needed. Seeing this, Chaac decided to remind them of their sacred purpose. He gazed upon the earth below and chose Tulan Zuyua, the village whose prayers had reached him with clarity.

With a swift motion, he struck the clouds with his axe.

The heavens trembled.

Lightning spiraled downward like a serpent of fire. It coiled around the central ceiba tree of the village, illuminating the night as though dawn had erupted at once. The villagers fell to their knees, shielding their eyes from the brilliance.

When the light faded, a figure stood beneath the ceiba.

It was Chaac himself, tall, imposing, his long curling nose shadowed beneath a crown of storm clouds. A serpent twined around his arm, its scales shimmering like raindrops. The air smelled of ozone and wet earth that had not yet fallen.

The people trembled, but Chaac spoke gently: “You have called to me. Your fields suffer, your children hunger. Yet the rains cannot come while the Four Chaacs are in disharmony. Help me restore balance.”

The elders asked how they could aid a god.

Chaac motioned toward the sky. “Each direction must be honored. Prepare offerings reflecting the colors of maize, red, white, black, and yellow. Carry them to the edges of your land. Your devotion will remind my brothers of their duty.”

The villagers worked through the night. Families gathered maize kernels of the four sacred colors. Children wove baskets. Elders crafted incense bundles. At dawn, four groups set out, east, west, north, south, carrying offerings with reverence.

As each group reached its horizon, they placed the offerings upon stone altars and spoke words of gratitude to the Chaac of that direction. Their prayers rose like warm air lifting into the heavens.

High above, the Four Chaacs paused. They felt the devotion of the people, recognition of each one’s importance. Slowly, their discord softened. Red Chaac bowed his head toward White Chaac. Black Chaac extended his hand to Yellow Chaac. Their unity hummed across the sky like wind returning after a long stillness.

Chaac raised his axe once more and struck the heart of a waiting storm cloud.

Thunder erupted.

Rain spilled from the heavens in great silver curtains. The villagers lifted their faces to the sky, laughing as water soaked their hair and clothing. The maize fields sighed with relief. Leaves unfurled. Soil drank deeply.

Chaac watched from beneath the ceiba tree, satisfaction in his storm-lit eyes. The Four Chaacs worked together again, their rains moving across the land in waves, east to west, north to south, each direction fulfilling its sacred role.

When the storm finally eased, Chaac stepped back toward the tree. The serpent around his arm flickered with lightning, then vanished into smoke. Before disappearing into the sky, Chaac left the villagers with a final message carved in thunder:

“Rains flow where harmony reigns. Honor every direction, and the world will nourish you.”

He rose into the clouds, the axe lifting the storm as though drawing a curtain across the sky. The people of Tulan Zuyua tended their fields with renewed hope, knowing that Chaac listened, not just to offerings, but to unity itself.

Learn the ancient stories behind deities of light, storm, and shadow from cultures across the world

Author’s Note

Chaac’s myth reminds us that balance, between directions, forces, and communities, is essential to sustaining life. Rain arrives not through dominance but cooperation. The Maya vision of harmony among the Four Chaacs reflects a deeper truth: the world thrives when all elements work together.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What domains does Chaac govern?

A: Rain, storms, lightning, and agricultural fertility.

Q2: What object does Chaac wield to release rain?

A: A lightning axe.

Q3: How many Chaacs exist in cardinal direction form?

A: Four; East, North, West, and South.

Q4: Why did drought occur in the myth?

A: The Four Chaacs fell into disharmony.

Q5: Where do rituals to Chaac often take place?

A: Temples, caves, cenotes, and mountaintop shrines.

Q6: What symbolizes lightning in Chaac’s mythology?

A: A celestial serpent descending from the sky.

Source: Maya Codices and Oral Traditions, Mesoamerica.

Source Origin: Maya Civilization, Mesoamerica (Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras)