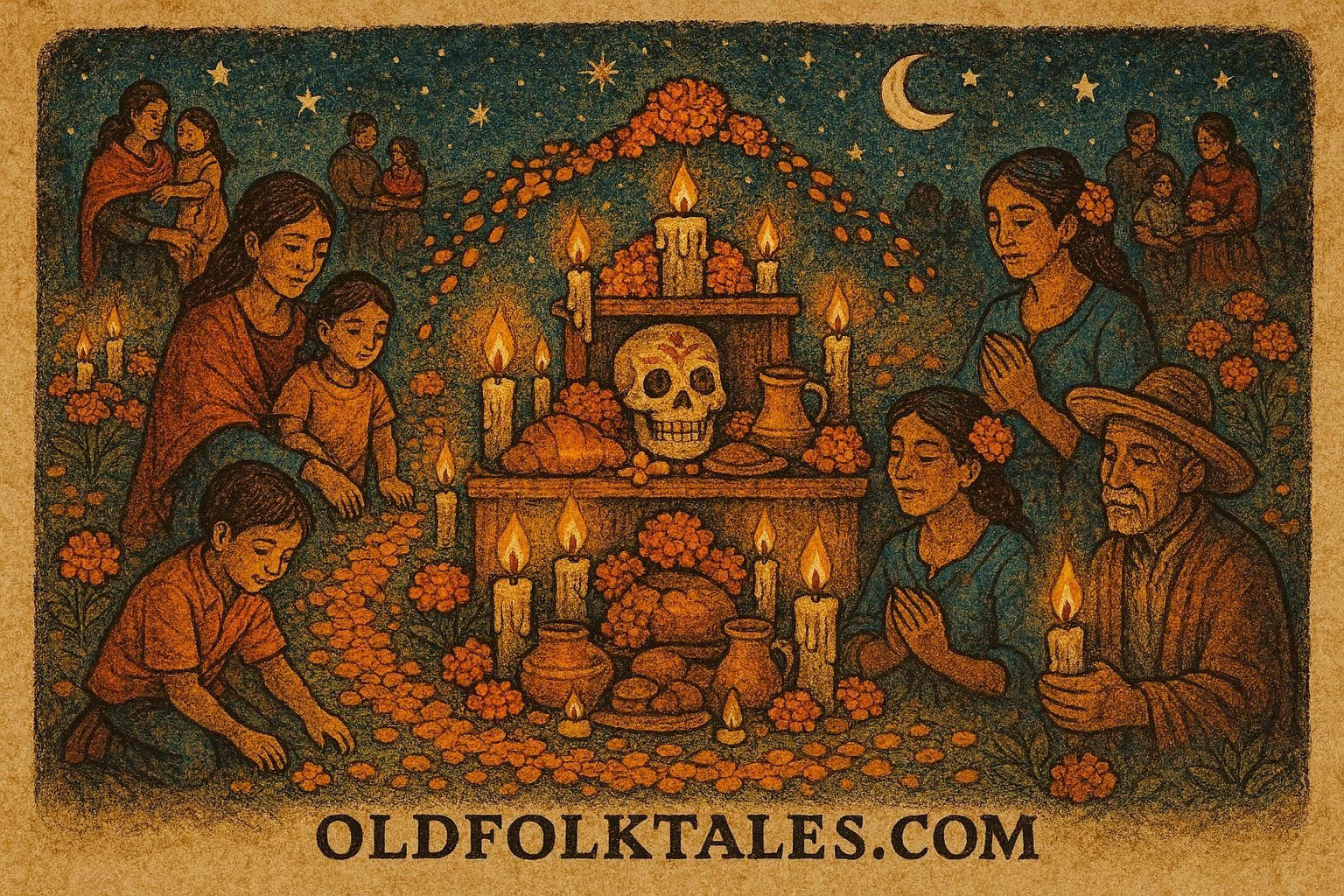

Each autumn, when the air thins and the veil between worlds grows translucent, Mexico blooms in marigold gold and candlelight. Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, is not a mournful rite but a celebration of continuity. For several days, families gather to welcome the souls of the departed, setting altars (ofrendas) adorned with photographs, sugar skulls, candles, and offerings of favorite foods. Streets fill with paper marigolds, music, and laughter; cemeteries glow through the night as families eat, pray, and tell stories beside the graves of their ancestors.

The modern Día de los Muertos, now recognized by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage, is a syncretic fusion of Indigenous and Catholic cosmologies. Before Spanish colonization, Mesoamerican peoples such as the Mexica (Aztec), Purepecha, Zapotec, and Maya practiced elaborate rituals honoring the spirits of the dead. These rites affirmed death as part of a cosmic cycle rather than an end. When Catholic missionaries introduced All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days in November, Indigenous people merged the two calendars, transforming missionary observance into a uniquely local, resilient form of ancestor veneration.

Traditionally, celebrations occur from October 31 to November 2, aligning with the Catholic calendar but infused with Indigenous timekeeping. The first night often honors children’s spirits (Día de los Angelitos), while the following days welcome adult souls. Families sweep and decorate graves, prepare special dishes like pan de muerto (bread of the dead), tamales, and mole, and adorn ofrendas with papel picado cutouts symbolizing wind and fragility. Marigold petals form paths leading from street to altar, guiding the returning souls home by their scent and color.

In many regions, especially in Michoacán, Oaxaca, and Mixquic, vigils last through the night. Candles flicker across the cemetery, illuminating laughter, prayer, and song. Death, once feared, becomes a companion to be remembered and fed. It is not uncommon for families to tell humorous stories of the deceased, reflecting the Mesoamerican view that remembrance keeps the dead truly alive.

Mythic Connection — The Sacred Return of Souls

Día de los Muertos draws on ancient Mesoamerican beliefs about the journey of the soul. Among the Mexica, death was a passage to Mictlán, the layered underworld ruled by the god Mictlantecuhtli and his consort Mictecacíhuatl, the Lady of the Dead. The journey was long and treacherous, requiring the aid of the hairless dog Xoloitzcuintli to guide the spirit across rivers and mountains. Offerings placed with the dead were meant to assist this voyage.

The modern altar echoes these beliefs. Its multi-tiered structure represents different planes of existence: heaven, earth, and the underworld. Each object carries symbolic weight. Water quenches the thirst of returning souls; salt purifies; candles illuminate the path; food offers sustenance; photographs summon memory. The marigold, cempasúchil in Nahuatl, was sacred to the sun god Tonatiuh, its golden hue symbolizing light and rebirth. Through these elements, Día de los Muertos becomes a dialogue across worlds, linking cosmology with household practice.

At its core, the festival expresses a cosmic rhythm: life feeds death, and death feeds life. The dead nourish the living with memory and blessing, while the living sustain the dead through ritual attention. The ofrenda is thus not a memorial but a table of reunion, a reaffirmation that time is cyclical and relational, not linear or final.

Social and Spiritual Symbolism

Beyond cosmology, Día de los Muertos reinforces social continuity. In Indigenous thought, community extends beyond the visible world. Ancestors remain participants in the moral and emotional life of their descendants. Preparing an ofrenda is an act of gratitude and kinship, an acknowledgment that the living owe their existence to those who came before. The sharing of food symbolizes reciprocity: just as the dead once fed the living, now the living feed the dead.

Modern observances vary by region and family. Urban celebrations may include parades, artistic installations, and costume festivals inspired by La Calavera Catrina, the elegant skeleton created by artist José Guadalupe Posada and popularized by Diego Rivera. Yet even these public spectacles retain a sacred undertone. Beneath the pageantry lies an ancient truth: remembrance is resistance against erasure.

Día de los Muertos also survives as an act of cultural identity. During centuries of colonization, suppression, and modernization, the festival carried Indigenous cosmology forward under Catholic cover. Today it stands as a testament to resilience, a living ritual that unites families, bridges generations, and reaffirms harmony between worlds.

Author’s Note

Día de los Muertos endures as a luminous expression of Mesoamerican spirituality. Its laughter amid loss, its flowers amid death, and its altars amid the living remind us that memory is sacred work. The ceremony does not deny mortality; it transforms it into relationship. Across centuries, this ritual has preserved a worldview where life and death remain bound by affection rather than fear.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What are the main dates of Día de los Muertos?

A: October 31 to November 2, corresponding to All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days.

Q2: What ancient deities are linked to the festival’s origins?

A: Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacíhuatl, rulers of the Aztec underworld, Mictlán.

Q3: What is the symbolic purpose of the marigold flower?

A: Its color and scent guide the souls of the dead back to the world of the living.

Q4: What is placed on an ofrenda and why?

A: Food, water, candles, salt, and photos—each element honors and aids returning souls.

Q5: How does Día de los Muertos express Indigenous cosmology?

A: It enacts cyclical time and the ongoing relationship between the living and the dead.

Q6: Why is Día de los Muertos considered a form of cultural resistance?

A: It preserved Indigenous beliefs under colonial rule and continues to affirm cultural identity today.