Before the rise of kingdoms and the naming of mountains, when the winds of the Tibetan plateau still carried the breath of creation, the gods gathered to confront a grim truth: demons were multiplying across the realms. They took the shapes of beasts, storms, princes, and beggars, feeding on greed, pride, and the unguarded hearts of humankind. Seeing the world tilt toward ruin, the celestial hosts turned their eyes upon the realm of mortals and resolved to send a champion, Gesar, who would stand between chaos and the living earth.

Thus was Gesar conceived, not born merely of flesh, but woven from divine mandate. The gods shaped him of wind and fire, tempering him in the radiance of the mountain deities. They gave him the sharp gaze of a falcon, the courage of the snow lion, and a destiny heavier than bronze. When his spirit was ready, they sent him into the womb of a humble woman in the land of Ling. In that quiet valley, he would begin life as a strange, small child, unruly, wild-haired, and feared by neighbors who sensed the fire in him.

From the moment he could walk, Gesar showed signs of his cosmic heritage. He wrestled spirits in his dreams and woke with the scent of thunder on his skin. He outran horses, spoke to river spirits, and stared down the shadows that prowled the edge of night. Yet his childhood was not one of triumph. Many despised him, calling him cursed or touched by demons. Their hostility forged in him a deep understanding of human frailty, the moral wound he would carry into adulthood: the knowledge that men could fear their own salvation.

The first great challenge came when the warlord Traklha, a shape-shifting demon disguised in human form, sought to seize Ling. His armies marched like a storm. The elders trembled; the kings bickered. But the gods whispered to Gesar, reminding him of his vow before birth. He stepped forward, still young, still mocked, and declared he would defend the valley. The people laughed, yet desperation forced their blessing.

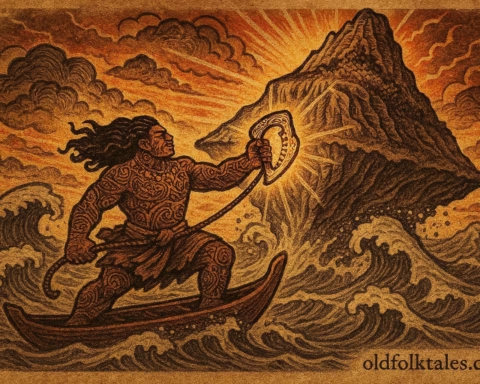

On the day of battle, Gesar mounted his miraculous steed, Kyang Go Karkar, born of the sky, swift as lightning. As the demon-warlord unleashed fire and illusion, Gesar invoked the gods of the mountains. Divine wind burst around him, tearing through the demon’s disguises. Their clash split the sky. At last, with a spear forged of heavenly light, Gesar struck down Traklha and scattered his army like dust across the plains.

The people of Ling crowned him King Gesar, their protector and champion. But kingship brought neither rest nor comfort. It was a mantle of solitude. The demons he defeated did not merely haunt the world, they mirrored the weaknesses of mortals, from greed to rage, ambition to envy. Gesar often questioned whether the greater enemy was the supernatural or the human heart. This doubt was the shadow that followed him through every campaign.

Soon came other foes: Shingti, the demon of the northern forests; Klu bTsun, the serpent queen of the rivers; and Hor, the cunning prince whose silver tongue hid a monstrous appetite for domination. Each enemy tested a different part of Gesar’s spirit. Against Shingti, he battled raw ferocity. Against the serpent queen, he learned restraint and mercy. Against Hor, he confronted deception so total that it almost shattered his trust in his own judgment.

Perhaps the greatest trial of all was his struggle against Lutsen, a demon who fed upon human desire. Lutsen brought no armies, he needed none. He whispered dreams of conquest into the ears of the proud and set kingdoms aflame without lifting a single claw. When Gesar confronted him, the demon did not summon storms or illusions. Instead, he offered Gesar what no god ever had: freedom from divine duty.

“Abandon your burdens,” Lutsen hissed. “Live for yourself. Let men choose their own ruin.”

For the first time, Gesar faltered. He saw, in a vision, a life without endless warfare, a life of peace among the people he protected. But in that same vision he saw the world collapsing under demonic rule, its mountains desecrated, its rivers poisoned by despair. And he understood: freedom without responsibility was only another kind of destruction.

With renewed resolve, Gesar shattered Lutsen’s enchantment and, invoking the compassion of the bodhisattvas, bound the demon so that he could no longer poison the hearts of humankind. In doing so, Gesar solidified not only his power but his purpose. He was not merely a warrior, he was a guardian of balance, a living symbol of the struggle between impulse and virtue.

Across countless battles that shook every corner of the plateau, Gesar restored harmony where darkness had taken root. Yet he never claimed triumph as his own. He remained humble, knowing that even the greatest hero is only a steward of the world, not its master.

In time, when the realms grew quiet and the demons retreated into the cracks of forgotten places, Gesar’s work was complete. The gods called him home. He rose from the land of Ling in a blaze of golden fire, leaving behind a legacy carried in songs, chants, and the breath of storytellers for centuries.

For though he ascended to the heavens, the struggle he embodied, between chaos and courage, temptation and duty, remains eternal in the hearts of humankind.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Gesar is celebrated across Mongolia, Tibet, and surrounding regions as a symbol of courage, moral clarity, and cosmic responsibility. His epic is believed to be the world’s longest oral tradition and continues to shape cultural identity, spiritual practice, and the understanding of heroism.

KNOWLEDGE CHECK

-

Why did the gods create and send Gesar into the world?

-

How did Gesar’s childhood shape his moral struggle?

-

What was Traklha’s true nature?

-

What temptation did the demon Lutsen offer Gesar?

-

What inner conflict determines Gesar’s growth throughout the epic?

-

How does Gesar’s departure from the mortal world symbolize his legacy?

CULTURAL ORIGIN: Tibetan and Mongolian epic tradition; Himalayan plateau oral literature.

SOURCE: The Epic of King Gesar, a centuries-old oral tradition preserved in Tibetan, Mongolian, Buryat, and related cultures.