Gule Wamkulu, translated as “The Great Dance”, is one of the most profound ritual traditions in Central and Southern Africa. Practiced among the Chewa people across Malawi, eastern Zambia, and parts of Mozambique, it forms the ceremonial core of the Nyau secret society. Nyau is both a religious order and a custodian of ancestral laws, oral memory, and spiritual authority. The origins of Gule Wamkulu stretch deep into pre-colonial Chewa cosmology, where ancestors were believed to dwell in a parallel realm and return in masked form to guide, discipline, and protect the living. UNESCO’s safeguarding records and regional ethnographic studies describe it as a living ritual system, one that has endured centuries of political, social, and religious transformation.

Description

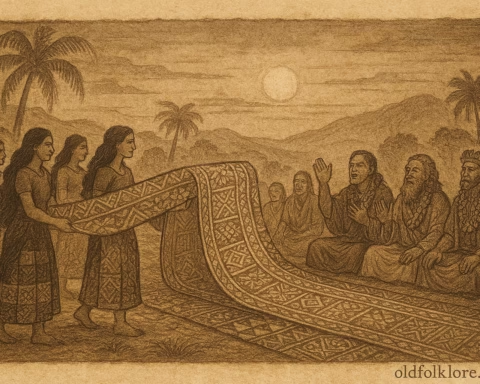

To witness Gule Wamkulu is to enter a world where the line between human and spirit dissolves. The ritual typically occurs during funerals, initiation ceremonies, the installation of chiefs, and community healing events. The performers, always initiated men, emerge wearing elaborate masks and full-body constructions made from wood, cloth, animal skins, reeds, and layers of raffia. These masks do not merely represent characters; they embody spirits, ancestors, moral archetypes, and warnings about social behavior.

Each figure in Gule Wamkulu has a name, personality, and story. Some masks depict ancestral spirits with elongated faces and red-painted eyes. Others portray animals such as hyenas, lions, and birds, symbolizing strength, greed, cunning, or transformation. Some masks represent exaggerated humans, corrupt leaders, reckless men, or immoral women—to teach moral lessons through satire and fear. The dancers move with charged energy, accompanied by intense drumming and choral singing from women and unmasked men who stand outside the Nyau circle.

The atmosphere is intentionally unsettling. Dust rises as performers rush through the open ground, the rattling of shells and seeds echoing like breath from another realm. Elders control the flow of the dance with precise signals; the order of appearance follows a strict spiritual hierarchy. Every movement reflects a coded message, obedience, humility, memory, respect for ancestors, and awareness of the consequences of dishonoring social laws.

Though the performance seems wild, it is tightly disciplined. Each dancer trains for years, learning how to embody his mask’s spirit without revealing his identity. Community members treat the masked figures with reverence and fear, addressing them as actual spirits rather than humans in costume. No uninitiated person is allowed to touch a mask or interfere with the ritual. Even today, Gule Wamkulu remains a powerful moral institution, reminding the Chewa that the ancestors observe all actions and that harmony must be maintained.

Mythic Connection

In Chewa cosmology, the world is shared between the living, the dead, and the yet-to-be-born. Gule Wamkulu is the ritual doorway through which these realms interact. According to ancestral teachings, the Nyau masks represent beings who emerge from bwalo, the sacred cemetery space believed to be the dwelling of the spirits. When a dancer wears a mask, he becomes a vessel for the ancestor it symbolizes. The community recognizes him not as a performer but as the ancestor made present.

Some myths recount that the first Nyau spirits were ancient ancestors who taught the Chewa how to maintain social stability. They used fear and spectacle to enforce moral discipline, ensuring that greed, disobedience, or disrespect toward elders did not shatter communal harmony. Other stories describe the masks as manifestations of mizimu, spirits who observe human behavior and intervene during funerals or crises to restore balance.

The symbolism of the masks encodes philosophical lessons. Animal figures reveal the qualities humans must learn to embrace or avoid. Grotesque human caricatures warn against vices that fracture society. High-ranking ancestral masks symbolize leadership, justice, and continuity. Each appearance reinforces the message that life is intertwined with the spiritual realm, and that the ancestors are never distant.

Gule Wamkulu also mirrors the Chewa understanding of nature as alive with sacred presence. Raffia represents the forest, the source of ancestral power. Animal skins and feathers link the human body to the wisdom of non-human beings. Drums echo the heartbeat of the earth. Through this ritual, the Chewa express a worldview where community, nature, and spirit form one interconnected whole.

Author’s Note

This entry presents Gule Wamkulu through its ancestral symbolism, ritual structure, and mythic worldview. It aims to illuminate how the Chewa maintain harmony with the spiritual realm through sacred performance and to show how this ancient tradition continues to shape identity and communal memory.

Knowledge Check

1. What is the central purpose of Gule Wamkulu?

To embody ancestral spirits and teach moral, social, and spiritual lessons through masked performance.

2. Why do performers wear masks and raffia costumes?

Because the costumes transform them into spirit beings, allowing ancestors to appear physically in the community.

3. When is Gule Wamkulu performed?

During funerals, initiations, chief installations, and major community ceremonies.

4. How does Gule Wamkulu reflect Chewa cosmology?

It demonstrates the belief that ancestors remain active and continue guiding the living.

5. Why are some masks intentionally frightening?

To enforce discipline, warn against immoral behavior, and teach community values.

6. What role do elders play during the ritual?

They control the sequence, guide performers, and ensure the spiritual and social rules are maintained.