Hel (Old Norse: Hel) is the somber and sovereign guardian of the Norse underworld that bears her name. Daughter of Loki and the giantess Angrboða, she is described in the Prose Edda as half-living and half-dead in appearance, a being who stands at the threshold between worlds. Unlike the heroic dead who feast in Valhalla or Fólkvangr, those who die from illness, age, or quiet passing travel downwards to her shadowed hall, Éljúðnir, situated deep beneath the roots of the cosmos.

Her domain is not one of fiery torment nor moral judgment, but of stillness, inevitability, and the natural quiet of death. Hel receives the departed with absolute authority, offering no false comfort yet performing her cosmic duty without cruelty. She is neither villain nor benefactor, she is necessity, the custodian of a realm where most souls eventually go.

Symbolically, Hel represents the boundary between mortality and the vast unknown. Her hall is described with stark imagery: high walls, a threshold named Fallandaforað (“falling to peril”), and a bed called “sick-bed.” Yet her rule is lawful, ancient, and essential to the Norse cosmological balance.

Mythic Story

In the age when the nine worlds were still young and the fates of their beings were only beginning to take shape, Odin cast his wandering eye across Jötunheim, where Angrboða dwelt in the ironwood. From her came three children with destinies heavy enough to bend the world: the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jörmungandr, and the girl Hel, solemn, quiet, and marked by a visage half fair and half pallid as a lifeless stone. Odin sensed the weight of prophecy upon them. Each child carried within them the potential to sway creation, and so he brought them from the wild places into the council of the gods.

Fenrir was raised among the Æsir for a time, Jörmungandr cast into the sea encircling Midgard, and Hel, grave and gazing with dark wisdom, was sent to the deep places beneath the world. Not as exile, but as keeper. For the realms of gods and mortals alike needed a guardian of death, someone who could receive the souls destined for quiet departure. Hel descended willingly, accepting a mantle that none among the living could bear.

Her journey downward was long and steep. Past cold caverns and whispering winds she traveled, until she reached the land that would be hers: a quiet expanse of stone halls and dim skies untouched by sun. There she raised her seat in Éljúðnir, its walls stark and silent, its great doors opening to the souls who traveled the downward path from Midgard.

Hel ruled without malice. She did not torment nor judge. She simply received, with the solemn responsibility given by Odin and affirmed by the workings of the cosmos. The old died and came to her; the sick crossed her threshold; those whose passing was without battle-wound or heroic blaze joined her realm. To them she offered the sameness of stillness, the long rest after the burden of life.

For generations, her realm remained undisturbed. Until Baldr died.

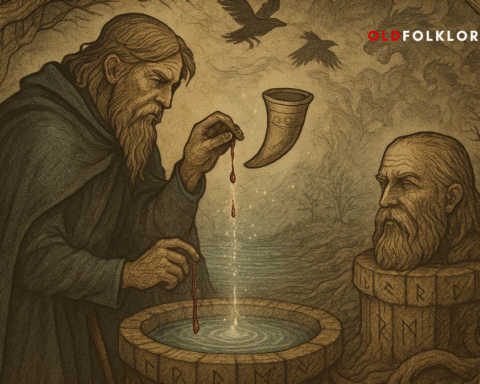

Baldr, radiant son of Odin and Frigg, the beloved of all the worlds, fell not by war or sickness but through trickery woven by Loki: the flight of a mistletoe dart that pierced him where no weapon should have harmed. Light went out of him, and the worlds sank into mourning. The Æsir sent Hermóðr, Baldr’s brother, riding upon Sleipnir down the long, dark road to Hel’s realm, pleading for Baldr’s return.

For nine nights Hermóðr rode through valleys where shadows clung to the air like mist. He crossed rivers, passed mountains, and finally reached the tall gates of Hel. His horse leapt over them, hooves striking the stone floor of Éljúðnir. There, in the quiet hall, Hel sat upon her high seat, her gaze steady, her face showing both compassion and the unmovable truth of her nature.

“What brings an Æsir to my hall?” she asked.

Hermóðr bowed deeply. “I come for Baldr, whose death has broken every heart in the worlds. Release him, I beg you.”

Hel regarded the silent figure of Baldr, who sat near her seat, pale and serene as winter’s first frost. She spoke with measured words: “If the worlds mourn him truly, if every being above weeps for him, he will be free to return. But if one creature refuses to shed a tear, he will remain here with me.”

It was a fair decree, for Hel acted not out of cruelty but the laws that governed death itself. The Æsir sent messengers across the nine worlds. Gods wept, giants cried, men and women shed tears, and even stones glistened with dew like sorrow. All wept for Baldr, save one. Loki, disguised as the giantess Þökk, refused to mourn. Her cold voice echoed: “Þökk will weep dry tears at Baldr’s burning. Let Hel keep what she has.”

Thus the condition was broken. Baldr remained in Hel’s realm, seated among the quiet dead until the distant day of Ragnarok.

Hel neither smiled nor scorned. She simply upheld the law of death: once taken, a soul cannot return unless the cosmos itself agrees. Even the grief of the gods could not overturn what fate had fixed.

In the end, Hel’s realm stands not as a place of punishment but as a reminder that death is the great leveling path, one no strength or beauty can escape. Her presence is the stillness at the world’s foundation, the quiet keeper who ensures that endings remain endings until time itself unravels.

Author’s Note

Hel’s myth teaches that death is not always the heroic blaze of battle nor the terror of judgment. In Norse belief, it is often a return to quietness, a realm governed by necessity rather than malice. Hel’s neutrality, her firm but fair guardianship, reminds us that endings are part of cosmic balance. Even the beloved must answer the call that every being eventually hears.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who are Hel’s parents?

A: Loki and the giantess Angrboða.

Q2: What type of dead does Hel rule over?

A: Those who die from sickness, age, or peaceful causes.

Q3: What is the name of Hel’s hall?

A: Éljúðnir.

Q4: Why does Baldr remain in Hel’s realm?

A: Because not every being in the worlds agreed to mourn him.

Q5: What is Hel’s realm traditionally like?

A: A quiet, shadowed underworld, not a place of fire or moral punishment.

Q6: What role does Hel symbolize in Norse cosmology?

A: The necessary custodian of death and the boundary between life and the unknown.

Source: Norse Mythology, Scandinavia.

Source Origin: Scandinavia (Norse Mythology)