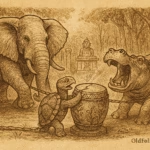

In the time when animals still walked and talked as people do, when the forest paths connected village to village across Yorubaland, there lived Ìjàpá the Tortoise and his wife Yásèrè. Their compound sat at the edge of the village, where the cooking smoke from their hearth mingled with the morning mist that rose from the forest floor. While other couples were known for their harmony and mutual respect, Ìjàpá and Yásèrè’s home often echoed with the sound of Ìjàpá’s scheming voice, plotting his next clever trick.

Ìjàpá, as everyone in the animal kingdom knew, carried greed in his heart as surely as he carried his shell on his back. His eyes were always calculating, always measuring what others had that he might take for himself. Poor Yásèrè, gentle and patient by nature, had learned to live with her husband’s selfish ways, though her heart often grew heavy with the burden of his endless manipulations.

Click to read all Myths & Legends – timeless stories of creation, fate, and the divine across every culture and continent

One bright morning, when the sun painted the palm fronds gold and the air was sweet with the scent of blooming flowers, a messenger arrived at their compound. The great chief of the animal kingdom was hosting a magnificent feast, and Ìjàpá and Yásèrè were both invited to attend. The messenger spoke of mountains of pounded yam, rivers of rich palm oil stew, platters of smoked fish and bush meat, and calabashes overflowing with palm wine. It would be a celebration like no other, a gathering where all the animals would eat, drink, and make merry until the stars filled the night sky.

Yásèrè’s face lit up with joy at the news. She loved such gatherings the laughter, the dancing, the warm fellowship of the community. But even as the messenger departed, Ìjàpá’s mind was already spinning like a spider weaving its web. He did not think of celebration or community. He thought only of how he could eat more than his fair share, how he could fill his belly while others went with less.

As Yásèrè began to prepare for the feast, wrapping her finest cloth around her waist and adorning herself with beads that clicked softly as she moved, Ìjàpá called her to him. His voice was low and conspiratorial, the way it always was when he was plotting something shameful.

“Wife,” he said, his eyes gleaming with cunning, “I have a plan that will ensure we get the best portions at this feast. You know how these gatherings are everyone scrambling for food, the best pieces disappearing before you can blink. But we shall be clever.”

Yásèrè’s heart sank. She knew that tone in her husband’s voice. Nothing good ever came from Ìjàpá’s plans. But she listened as he continued, her gentle nature making it difficult for her to refuse him outright.

“Here is what you must do,” Ìjàpá instructed, his voice dripping with self-satisfaction. “When we arrive at the feast, you must sing. Sing loudly, sing beautifully, sing so that everyone’s attention is on you and your lovely voice. Keep singing throughout the meal, without pause. While everyone is distracted by your performance, enchanted by your melodies, I will move quietly among the food, taking the choicest pieces, the largest portions. No one will notice me because all eyes will be on you.”

Yásèrè felt shame wash over her like cold water, but Ìjàpá was insistent. “This is how husband and wife should work together,” he said, though his words twisted the sacred bond of marriage into something ugly and selfish. “You sing, I eat, and we both benefit.”

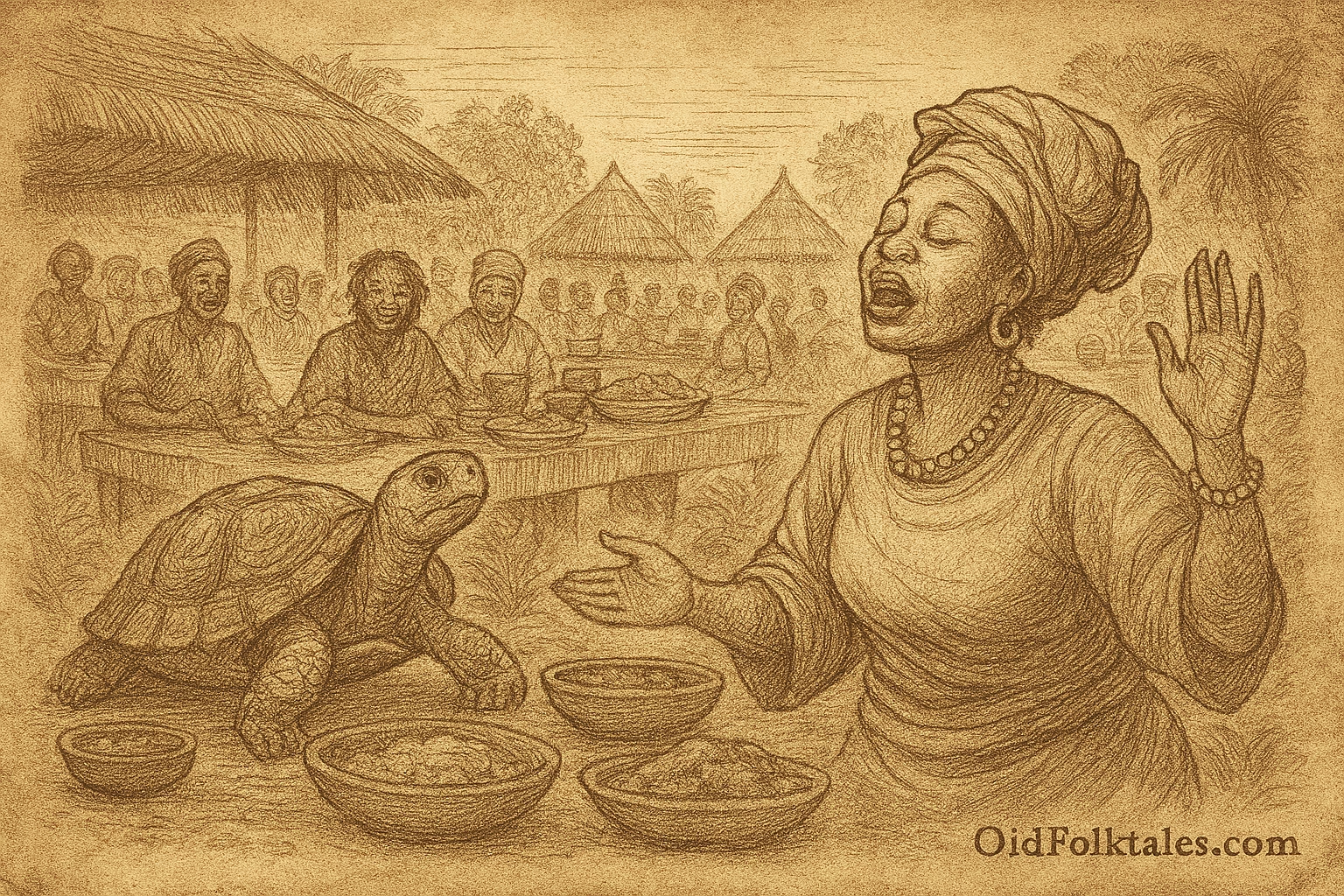

When they arrived at the feast, the gathering was even more spectacular than the messenger had described. The compound was alive with color and sound animals in their finest adornments, drummers setting rhythms that made the earth itself seem to dance, and tables laden with food that made mouths water and hearts glad. The chief sat in the place of honor, welcoming each guest with warmth and generosity.

True to her husband’s instructions, Yásèrè began to sing as soon as the feast commenced. Her voice rose sweet and clear above the din of celebration, and indeed, many animals paused to listen, their faces softening with pleasure at her beautiful melodies. The old songs of Yorubaland flowed from her lips songs of harvest and rain, of love and ancestors, of the forest and the sky.

But something unexpected happened. As Yásèrè sang, as her voice carried across the gathering, something loosened in her heart. The joy of the music, the warmth of the community, the delicious aromas surrounding her all of it awakened something she had suppressed for too long under Ìjàpá’s shadow. She forgot, for a blessed moment, about her husband’s scheme. She forgot about being merely a distraction in his selfish plot.

She reached for the food before her and ate with genuine pleasure. She laughed with other guests. She danced between songs, her beads clicking a rhythm of their own. She was, for the first time in a long while, simply herself not a tool in someone else’s manipulation, but a person enjoying life’s simple blessings.

Meanwhile, Ìjàpá lurked at the edges of the gathering, growing more and more furious with each passing moment. Where was the signal from Yásèrè? Why wasn’t she keeping the crowd’s attention focused solely on her performance? Why were people starting to return to their eating and conversations? His carefully laid plan was crumbling like old clay.

His greed began to boil over like a pot left too long on the fire. Unable to contain himself any longer, unable to wait for the distraction he’d counted on, Ìjàpá threw caution aside. He rushed forward from his hiding spot, his short legs carrying him as fast as they could toward the choicest platter of meat. His shell scraped against the ground, his breathing was heavy with desperate hunger, and his eyes saw nothing but the food he coveted.

But everyone saw him.

The entire gathering turned to witness Ìjàpá’s shameful display this creature who had been invited as an honored guest, now scrambling and snatching at food like a thief in the night. The chief stood, his face dark with disappointment. Other animals gasped and murmured. Children pointed. Even the drummers stopped their rhythms.

“Ìjàpá!” the chief’s voice rang out like thunder. “Is this how you honor my hospitality? Is this the gratitude you show for the invitation to my table?”

Ìjàpá froze, a piece of meat still clutched in his guilty hands. There was nowhere to hide, no clever words that could explain away what everyone had witnessed. The shame that descended upon him was complete and total. Yásèrè stood among the other guests, her face burning with embarrassment not for herself, but for the humiliation her husband had brought upon them both.

The chief spoke again, his words measured but heavy with judgment: “Leave this place, Ìjàpá. Take your greed with you. You have shown that you cannot be trusted to share in the fellowship of decent creatures. Perhaps in your solitude, you will learn what you have failed to understand in company.”

And so Ìjàpá, the great trickster who thought himself so clever, shuffled away from the feast in disgrace. His shell, which he usually carried with such prideful swagger, seemed heavier than ever, weighed down not by its physical burden but by the shame of his exposure. Yásèrè followed at a distance, her joy from the evening completely extinguished, wondering how long she would have to bear the consequences of her husband’s selfishness.

The feast continued without them, but the story of Ìjàpá’s greed spread quickly, as such stories do, becoming a tale told and retold wherever people gathered, a warning carved into the memory of the community.

The Moral Lesson

This profound Yoruba tale teaches us that greed corrupts not only the greedy but also those they manipulate into serving their selfish schemes. Ìjàpá’s attempt to use his wife as a tool for his own gain represents a betrayal of the sacred trust between spouses and partners. The story warns against allowing selfishness to poison our relationships and reminds us that manipulation especially within families destroys the bonds of love and respect that should hold us together. True partnership is built on mutual care and shared values, not on using others to satisfy our own desires. As the Yoruba say, “Ìwà l’ẹwà” character is beauty and no amount of cleverness can compensate for a character corrupted by greed.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who are Ìjàpá and Yásèrè in Yoruba folklore and what is their relationship?

A: Ìjàpá is the tortoise trickster character famous throughout Yoruba folklore, known for his cunning and greed. Yásèrè is his wife, often portrayed as gentle and patient, who frequently becomes entangled in her husband’s schemes. Their relationship represents the strain that selfishness and manipulation place on family bonds.

Q2: What was Ìjàpá’s plan at the feast and why did it fail?

A: Ìjàpá instructed his wife Yásèrè to sing loudly throughout the feast to distract the other guests while he secretly stole the best food. The plan failed because Yásèrè, caught up in the genuine joy of the celebration, forgot about the scheme and began eating and enjoying herself. This forced Ìjàpá to act rashly and openly, leading to his public humiliation.

Q3: What does Yásèrè’s behavior at the feast reveal about human nature?

A: Yásèrè’s forgetting of her husband’s scheme reveals that genuine joy, community, and authentic connection are more powerful than manipulation and greed. When surrounded by warmth and celebration, her true, generous nature emerged, showing that people naturally gravitate toward authentic fellowship rather than selfish deception.

Q4: Why was Ìjàpá’s humiliation at the feast particularly severe?

A: Ìjàpá’s humiliation was severe because he violated the sacred bonds of hospitality and guest behavior in Yoruba culture. He was an honored guest at the chief’s feast, yet he acted like a thief. His exposure was public and undeniable, witnessed by the entire animal community, making his shame complete and his reputation permanently damaged.

Q5: What does this story teach about marriage and partnership?

A: The story teaches that partnerships and marriages should be based on mutual respect, shared values, and genuine care not on one person using the other as a tool for selfish gain. Ìjàpá’s manipulation of Yásèrè represents a profound betrayal of marital trust, showing how greed can corrupt even the most intimate relationships.

Q6: How does this tale reflect Yoruba cultural values about community and sharing?

A: The feast setting represents the Yoruba cultural emphasis on communal celebration, generosity, and shared abundance. Ìjàpá’s greedy behavior stands in stark contrast to these values, showing him as someone who violates the social contract of community life. The chief’s response public shaming and expulsion demonstrates how Yoruba society traditionally dealt with those who put selfish interests above communal harmony.

Source: Adapted from The Laws and Customs of the Yoruba People by A. K. Ajisafe (1924), section on tortoise tales, and from oral Yoruba traditions widely recorded throughout southwestern Nigeria.

Cultural Origin: Yoruba People, Southwestern Nigeria, West Africa