The Ijele Masquerade, often called the “king of masquerades,” stands as one of the most monumental ritual embodiments in West Africa. Rooted in Igbo cultural regions, particularly Arochukwu, Anambra, and surrounding communities, it evolved from ancestral masking systems tied to governance, memory, and sacred order. Early ethnographic records describe Ijele as a composite creation representing a palace, a kingdom, or a layered spirit-world structure. Over generations, its symbolism expanded, becoming the pinnacle of Igbo masquerade aesthetics.

In 2008, UNESCO recognized the Ijele as a cultural treasure requiring safeguarding. This acknowledgment reinforced its significance not only as performance art but as a living spiritual technology that binds community, ancestral reverence, and cosmic order into a single breathtaking form.

Description

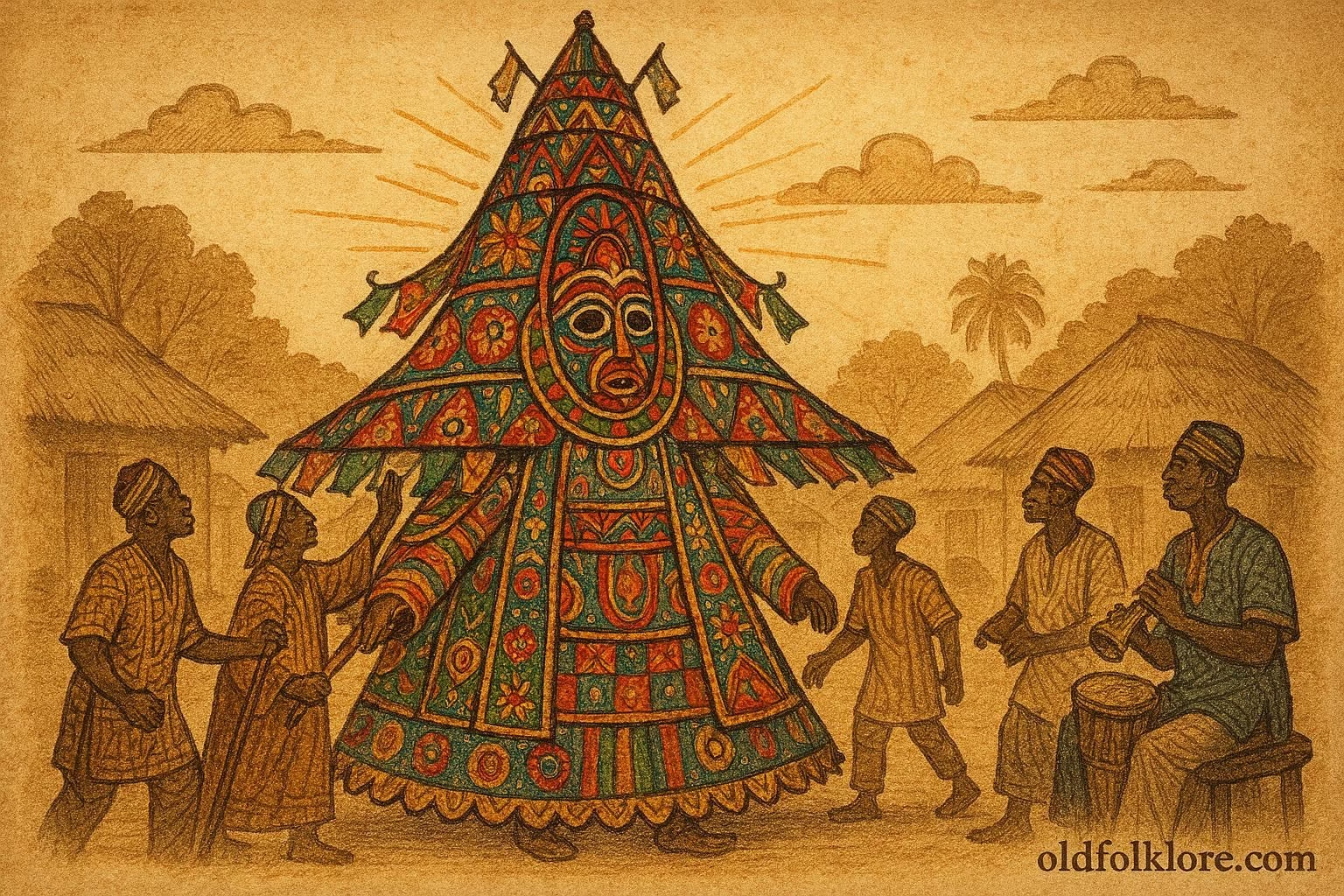

The Ijele Masquerade is immediately recognizable for its extraordinary height, often reaching 12 to 15 feet, and sometimes taller depending on the community’s tradition. Built from bamboo, richly dyed cloths, mirrored surfaces, symbolic figurines, and elaborately patterned decorations, the mask forms a massive cylindrical tower. The structure itself becomes a moving world: miniature animals, warriors, domestic scenes, market stalls, shrines, and ancestral motifs are carefully arranged on the tiers of the mask. To witness an Ijele is to see a small cosmos placed atop a single performer.

Its construction requires months of specialized labor. Artisans gather bamboo, cure it, and bind it into an internal frame. Women often weave the cloth strips and bright textiles that decorate the layers, while men carve the figurines and paint the designs. This collaborative process mirrors Igbo views of community balance: everyone contributes, but the final shrine-mask stands as the unified expression of the group.

Ijele does not appear casually. It is reserved for moments of profound communal significance, funerals of titled elders, major festivals, end-of-harvest thanksgiving, or rare honor ceremonies. Its arrival is carefully timed. Musicians begin with the low rumble of the igba drums, followed by the sharp accents of the ogene bell. The crowd grows silent, and from the edge of the village square, the towering form sways into view, guided by ritual assistants called ndi olu. These attendants help stabilize the structure and maintain the sacred pacing of the performance.

The performer inside must be spiritually prepared and physically gifted. Because the mask is so heavy, the dancer trains for endurance and balance. During performance, he moves with slow grandeur, evoking authority rather than speed. Each step, pause, and turn is symbolic: the swaying motion represents the rhythm of life; the circular turns echo the cycle of seasons and human destiny; the leaning gestures reflect both humility and cosmic power.

Nothing about Ijele is random. Every symbol on its surface carries meaning. Birds often represent spiritual messengers. Snakes can symbolize ancestral guardianship or cyclical renewal. Warrior figurines recall ancestral defense of the land. Household scenes affirm the importance of community cohesion. Decorative mirrors reflect light, suggesting the ability to see beyond the mundane world. Together, these motifs express a worldview in which life, spirit, society, and cosmos are interwoven.

The most dramatic moment in the performance comes when Ijele completes a slow rotation at the center of the square. Elders describe this motion as a ritual blessing. As the massive figure turns, its topmost decorations shimmer in the sunlight, casting shifting reflections across the spectators. People whisper prayers, offer kola nut, or touch the earth in reverence. In these moments, the masquerade is not merely entertainment; it becomes a transient portal between the living and the ancestral realm.

While variations exist across Igbo regions, Arochukwu, for example, claims the primordial origin of the Ijele, the structure’s purpose remains consistent: to embody the highest prestige, collective memory, and spiritual authority. Some communities add smaller masquerades that accompany the Ijele. These satellite masks prepare the ground, clear spiritual obstructions, or praise the towering figure with dance and song. Their interaction reinforces the hierarchy of sacred power.

In modern times, the Ijele survives as a proud emblem of Igbo identity. Although tourism occasionally intersects with its performance, communities maintain strict boundaries around the sacred protocols. Costumes cannot be touched casually, and the performer is often shielded before and after appearing. Through these measures, the ritual sustains its dignity while adapting to contemporary cultural life.

Mythic Connection

The Ijele is often seen as a symbolic container of spirit presence. In Igbo cosmology, ancestors remain active participants in community life. Accordingly, the Ijele functions as a mobile palace, a structured world in which ancestral forces observe, guide, and bless the living. Its towering height points upward toward the sky realm of spirit; its grounded steps connect it to the earth deity, Ala. In this way, the masquerade bridges the universe’s visible and invisible layers.

Author’s Note

This article examined the Ijele Masquerade as a monumental expression of Igbo cosmology, ancestral authority, and communal identity. It traced its origins, symbolic elements, performance structure, and continuing relevance in modern cultural life.

Knowledge Check

1. What makes Ijele structurally unique?

Its towering height, bamboo frame, and multi-tiered symbolic decorations.

2. Why is Ijele associated with prestige?

It appears only during major rituals, honoring elders, ancestors, and communal renewal.

3. What do the figurines on Ijele represent?

Animals, warriors, and household motifs symbolizing spiritual and social meanings.

4. How is Ijele connected to Igbo cosmology?

It acts as a moving palace linking the living with ancestral and cosmic realms.

5. Why does the dancer require special training?

The mask is heavy and requires balance, stamina, and ritual preparation.

6. How is Ijele preserved today?

Through community protocols, artisanship, and UNESCO safeguarding frameworks.