In the days when the great famine swept across the land, the people suffered terribly. The crops had withered in the fields, leaving families desperate for anything they could find to fill their empty stomachs. They dug frantically in the hard earth for insects, scraped together bitter weeds, and pulled up stringy roots anything to keep themselves alive through those hungry times.

Among these suffering people lived a man named Kenkebe, his wife, their young son, and his elderly mother. As the days wore on and their situation grew more desperate, Kenkebe’s wife turned to her husband with worried eyes. “Go once more to my father, Kenkebe,” she pleaded. “He has helped us before. Perhaps he has a little corn he could spare for us now.”

At dawn the next morning, Kenkebe set off on the long walk to his father-in-law’s village. The journey was difficult, but when he finally arrived, he was welcomed with genuine warmth and kindness. By fortunate timing, an ox had just been slaughtered, and Kenkebe ate ravenously, stuffing himself until his belly was full and his hunger finally satisfied.

“What news do you bring, my son?” his father-in-law asked once Kenkebe had eaten his fill.

“Father, it is terrible,” Kenkebe replied with downcast eyes. “We have not a single bite left in the house. We are starving. Could you possibly spare us a little corn? We are dying of hunger.”

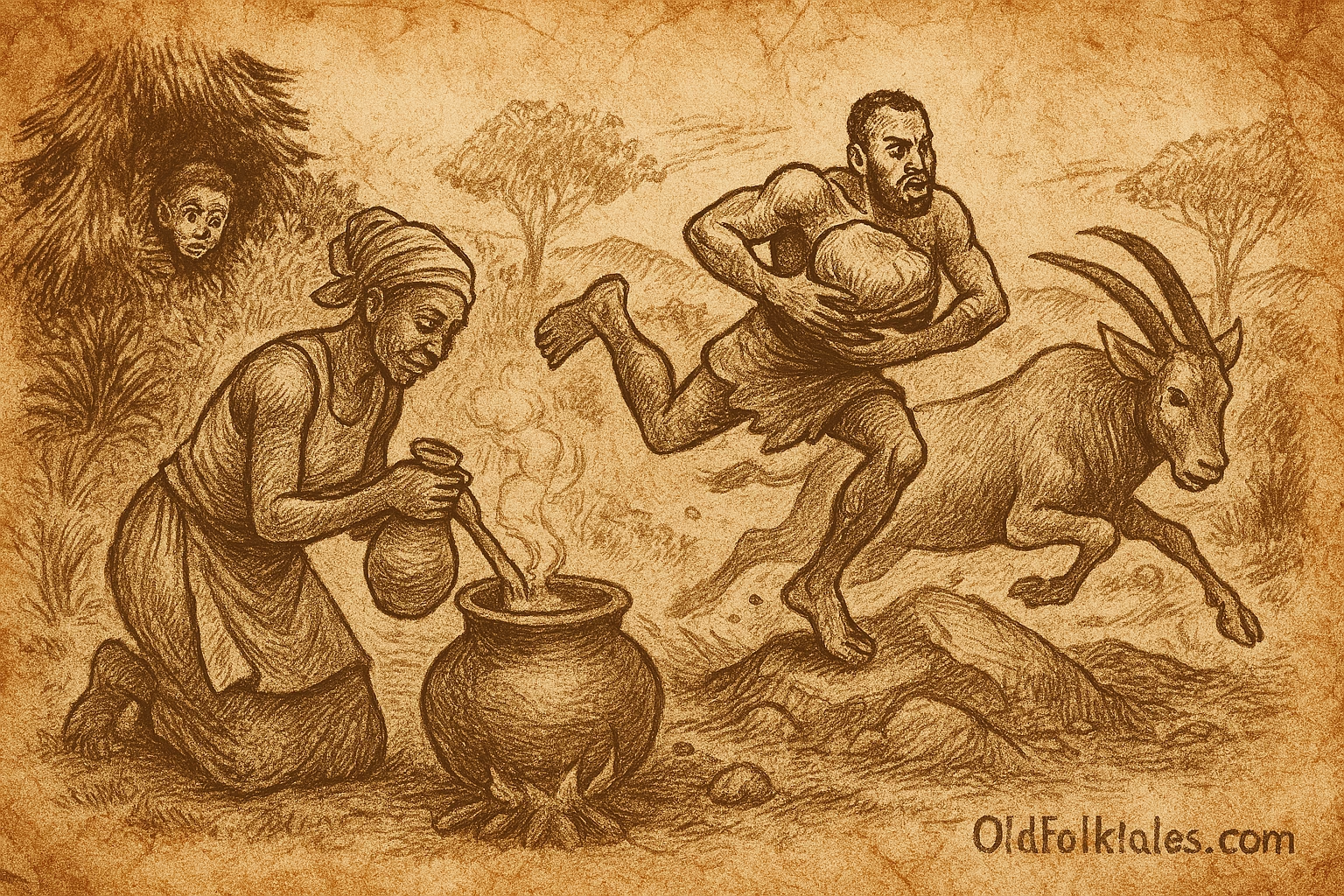

Moved by compassion, his father-in-law generously gave him seven heavy bags of precious millet more than enough to feed his family through the famine. His sisters-in-law volunteered to help carry the bags, and together they walked toward Kenkebe’s home. But when they reached the valley close to his village, a dark thought entered Kenkebe’s mind.

“Put down the bags here,” he told the women abruptly. “I am so near home now that I can manage on my own.” The girls, trusting and unsuspecting, set down their burdens and returned to their father’s house.

As soon as they were out of sight, Kenkebe revealed his true nature. One by one, he carried the seven bags of millet to a hidden cave, where he concealed them beneath a large rock. His family would never know of this abundance. Taking just a small portion of the millet, he ground it very fine and shaped it into little cakes that looked exactly like nongwe roots the bitter roots his family had been eating. He then dug up some real nongwe roots, placed them in his bag, and walked home wearing a mask of false despair.

“Alas!” he cried to his wife when he arrived. “There is also great famine on your father’s side of the land. The situation is so terrible that I actually found the people eating their own flesh, they are so desperately famished!”

His wife gasped in horror. Kenkebe ordered her to make a fire, then pretended to cut a piece of flesh from his own thigh. “This is what they are doing in your father’s village,” he said grimly. “Now, my wife, let us do the same to survive.” His trusting wife, believing his terrible lies, actually cut a piece from her own thigh and set it to roast on the fire. She did not realize that Kenkebe was secretly roasting ox meat he had hidden away from his father-in-law’s feast.

The couple’s young son, watching carefully, noticed something strange. “Father, why does your piece of meat smell so wonderfully nice as it roasts, while Mother’s does not?” he asked innocently.

Kenkebe answered quickly, “Because it is taken from the leg of a man, my son.”

After this cruel deception, Kenkebe gave his wife some of the bitter nongwe roots to cook while keeping for himself the millet cakes he had secretly prepared. Again, the observant boy noticed the difference. “Father, why do your nongwes smell so delicious while they roast, but Mother’s do not?”

“It is because they were dug by a man,” Kenkebe replied smoothly. As he rose to leave the hut, one of his false nongwe cakes rolled off his lap and dropped unseen to the floor. The hungry boy, still not satisfied, quickly snatched it up. Breaking it in half, he ate one portion and gave the other to his mother.

“This is no root!” she exclaimed, examining it closely. “This nongwe is made of millet!”

The truth struck her like lightning. Early the next morning, she and her son awoke and watched as Kenkebe crept quietly from the hut, carrying the cooking pot. They followed him soundlessly through the gray dawn and saw him go directly to the cave. Working together, mother and son pushed a massive boulder toward the selfish man.

When Kenkebe heard the grinding noise of the stone, he looked up in terror. The boulder was rolling straight toward him! He leaped away and rushed frantically down the valley, the great stone pursuing him relentlessly. Into the cold river he splashed, emerging dripping wet on the other side, then sprinting over hills and through dales with the boulder always close behind. This wild chase continued throughout the entire day.

At nightfall, Kenkebe staggered back to his own hut, exhausted and defeated. The boulder stopped there too, as if standing guard. Inside, his wife was calmly grinding millet from one of the bags she had retrieved from the cave.

“Why do you cry as if you were a child?” she asked coldly.

“I cry because I am very tired and very hungry,” he moaned pitifully. “I have lost my bag and mantle in the river, my clubs and everything that was mine.”

His wife held up his mantle, which she had picked up from the riverbank. “You have behaved like a bad and selfish scoundrel,” she said firmly. “And there is no food for you tonight.”

The following day, seeking to restore himself, Kenkebe took his spear and his two dogs Tumtumse and Mbambozozele and went hunting. Fortune smiled on him, and he managed to capture an eland cow with her young calf, which he drove home. He cut one ear from the calf, roasted it in the fire, and found it deliciously fat. Unable to resist, he cut and cooked the second ear as well.

Small indulgences lead to larger ones, and soon Kenkebe hungered for the entire calf. But a practical problem stopped him: if he killed the calf, the mother eland would not let down her milk. He called his dogs and asked Tumtumse, “If I kill the calf, will you imitate it and suck the eland cow for me?”

The honest dog replied, “No, I will bark like a dog.”

“Get out of my sight, you miserable cur!” Kenkebe shouted angrily, throwing a stone. Tumtumse ran off to seek a better master. Turning to Mbambozozele, he asked the same question. This dog, fond of milk and willing to deceive, agreed. So Kenkebe killed the calf, roasted and ate it, wrapping the calf’s skin around Mbambozozele so the eland mother would be fooled.

The trick worked at first, but Mbambozozele grew greedy like his master and wanted to suck too long. When Kenkebe struck him with a stick, the dog howled, revealing the deception. The eland cow, seeing how she had been tricked, charged Kenkebe with her sharp horns. He ran desperately until his wife called out, “Quickly, Kenkebe! Jump on that big rock!” He did so, and the eland, unable to stop her charge, rammed the rock with such fury that her neck broke.

The couple decided to cook the eland, but their fire had died. The nearest fire was in a village of cannibals over the hill. Too cowardly to go himself, Kenkebe sent his son, warning him not to take any meat. But the boy disobeyed, hiding a bit in his kaross.

At the cannibal village, an old woman gave him fire in a gourd. He gave her the meat, saying, “Do not eat it until I am long gone.” But as soon as he left, she began roasting it. The other cannibals smelled it and came running. So ravenous were they that they devoured not only the meat but the old woman, the fire, and even the ashes!

Sniffing the boy’s trail, the cannibals pursued him home. “Hide yourselves! The cannibals are coming!” he shouted. The mother jumped into a thick bush, the grandmother covered herself in ashes, Kenkebe climbed a tree clutching the eland breast, and the boy slipped into an antbear hole. The cannibals found and devoured the grandmother, then Kenkebe and the eland breast. They found the mother but were too full, so they took her captive.

That clever woman immediately planned her escape. She brewed the cannibals such delicious beer that they became roaring drunk and fell asleep. While they snored, she tiptoed out, barred the door, and set fire to the hut. Every cannibal burned alive. She then found her son, and together they had a joyful reunion.

Click to read all Myths & Legends – timeless stories of creation, fate, and the divine across every culture and continent

The Moral of the Story

This tale teaches us that selfishness and greed bring their own punishment. Kenkebe’s refusal to share with his starving family, his elaborate deceptions, and his continued self-serving choices led to one disaster after another. Among the Xhosa people, sharing food with those present is not merely politeness it is a sacred duty. The saying “We are all bridegrooms, Kenkebe” reminds us that everyone is entitled to their portion, and that those who hoard abundance while others starve will ultimately face consequences. True survival comes not from hoarding, but from community and generosity.

Knowledge Check

Q1: Who is Kenkebe in this South African folk tale and what is his main character flaw?

A1: Kenkebe is the protagonist of this traditional Xhosa story, a husband and father whose defining character flaw is extreme selfishness and greed. During a great famine, he hides seven bags of millet from his starving family, deceiving them into believing there is no food available while he secretly eats well. His selfish nature ultimately leads to his downfall and death.

Q2: What is the cultural significance of the saying “We are all bridegrooms, Kenkebe” among the Xhosa people?

A2: This saying originates from this very story and is used among the Xhosa people to call out anyone who refuses to share food readily. It means “We are all entitled to a portion, you greedy one.” In Xhosa culture, it is customary to share one’s food with any person present, making Kenkebe’s hoarding a serious cultural transgression that warranted being memorialized in this proverb.

Q3: What symbolic role does the boulder play in the story of Kenkebe?

A3: The boulder serves as an instrument of justice and consequence in the tale. When Kenkebe’s wife and son discover his deception about the hidden millet, they push a boulder toward him that then pursues him relentlessly throughout the day. The boulder symbolizes how guilt and the consequences of selfish actions follow wrongdoers, eventually catching up with them no matter how far they run.

Q4: What lesson do Kenkebe’s two dogs, Tumtumse and Mbambozozele, teach in this African folk tale?

A4: The two dogs represent contrasting moral choices. Tumtumse, the honest dog who refuses to participate in Kenkebe’s deception, leaves to find a better master showing the virtue of maintaining integrity even when it’s difficult. Mbambozozele, who agrees to help deceive the eland cow, represents how participating in dishonest schemes leads to bad outcomes. His greed and the resulting howl expose the trick, bringing consequences upon both him and his master.

Q5: How does Kenkebe’s wife demonstrate intelligence and resourcefulness in this Xhosa tale?

A5: Kenkebe’s wife shows remarkable cleverness throughout the story. She discovers her husband’s deception by recognizing that the fake nongwe root is actually made of millet. She orchestrates his punishment with the boulder and retrieves the hidden food. Most impressively, when captured by cannibals, she saves herself by brewing irresistible beer to make them drunk, then burning down their hut while they sleep a perfect example of using wit over strength.

Q6: What does this South African folk tale teach about community values during times of hardship?

A6: The story emphasizes that survival during hardship depends on community cooperation and sharing, not individual hoarding. While the community suffered during the famine, Kenkebe’s father-in-law generously gave seven bags of millet more than enough to share. Kenkebe’s refusal to share this abundance with his family violated the fundamental Xhosa value of communal support. The tale warns that those who prioritize self-preservation over community welfare will ultimately face isolation and destruction.

Source: Adapted from “Myths and Legends of Southern Africa” told by Penny Miller

Cultural Origin: Xhosa People, South Africa (Eastern Cape and surrounding regions)