The Lobisón is a feared were-creature from northern Spain, particularly Asturias and Galicia. Closely related to other Iberian shapeshifters like the Portuguese Lobishomen, the Lobisón is deeply embedded in local folklore and often described as a cursed individual who transforms into a wolf or wolf-dog hybrid. Folkloric accounts, collected in the 19th century, emphasize the moral and ritualistic causes of the transformation rather than purely physical explanations, highlighting its role as a cautionary figure.

Appearance

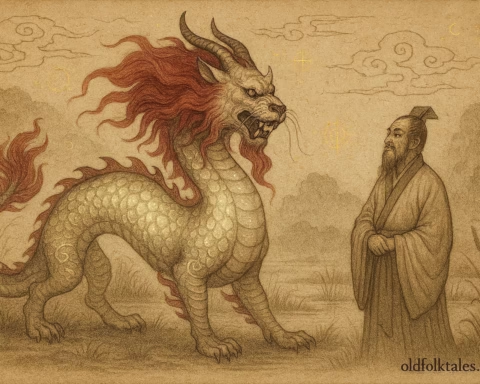

In human form, the Lobisón is sometimes indistinguishable from ordinary men, though folklore notes subtle signs: a peculiar gait, nocturnal habits, or unusual hairiness.

Relive the heroic sagas of every age – stories of triumph, tragedy, and timeless valor

In transformed form:

- Usually described as a wolf, dog, or hybrid of human and wolf

- Larger and more menacing than ordinary wolves, with glowing eyes in some tales

- Occasionally retains human-like features: hands, partial face, or upright posture

- Tracks may have anomalies, such as backward-facing footprints

- Some accounts describe fur in unusual shades (dark gray, black, or mottled)

This dual appearance reflects the Lobisón’s liminal nature, straddling human civilization and the wild, night-bound world.

Behavior and Powers

The Lobisón is traditionally nocturnal, active primarily under moonlight. Folklore emphasizes these behaviors:

- Transformation Timing: Often tied to the full moon, festival nights, or ritual errors.

- Cunning Predation: Wolves, livestock, or humans may be attacked; the creature often avoids direct confrontation with communities unless provoked.

- Supernatural Strength: Larger and faster than ordinary wolves, capable of eluding hunters or overpowering livestock.

- Wanderer’s Curse: Some stories portray the Lobisón as fated to roam endlessly, unable to rest due to ancestral or ritual misdeeds.

- Ritual Sensitivity: Breaking taboos (like violating holy days, failing baptismal rites, or committing sin) can trigger transformation.

Unlike monsters that kill indiscriminately, the Lobisón often embodies moral and cosmic justice, punishing transgression or neglect of ritual duties. In some accounts, the curse can only be lifted through confession, religious intervention, or ancestral reconciliation.

Myths, Beliefs, and Rituals

- Family and Ritual Causes:

Stories frequently link the curse to family lineage: a man might become a Lobisón if he is the seventh son, born under irregular circumstances, or fails a ritual (baptism, feast-day observance). - Community Defense:

Villagers were said to protect themselves using holy water, prayers, silver objects, or trained dogs. Some communities had ritualized “Lobisón hunts,” combining communal vigilance with spiritual safeguards. - Witchcraft and Malediction:

Certain variants hold that witches (meigasor feiticeiras) could curse a man to become a Lobisón for vengeance or moral correction. These interactions highlight the intertwined roles of magic and morality in Iberian folklore. - Moral Lessons:

The Lobisón warns of sin, family neglect, or disobedience to religious customs. Tales emphasize consequences for moral or social failings rather than mere terror. - Regional Variants:

- Asturias: The Lobisón is often wolf-like, tied to mountain forests and lunar cycles.

- Galicia: Sometimes portrayed more dog-like or humanoid; some stories describe cursed wanderers who can partially retain speech or human cognition.

- Folk Storytelling:

These tales were told by elders as cautionary narratives for children, or shared during communal festivals, emphasizing moral conduct, family respect, and vigilance in rural life.

Symbolism

The Lobisón embodies several overlapping symbolic themes:

- Moral and Ritual Consequences: Human transgression, family neglect, or failure to observe religious duties results in transformation.

- Human vs. Wild Duality: Reflects the tension between societal norms and primal instincts.

- Night and Wilderness: The creature’s nocturnal habits symbolize danger lurking beyond civilization.

- Lineage and Ancestral Memory: Curses affecting descendants echo fears about inherited sin and moral responsibility.

- Witchcraft and Cosmic Justice: Interaction with magical forces emphasizes vulnerability to unseen spiritual powers.

Cultural Role

In Asturias and Galicia, the Lobisón is more than folklore; it functions as a tool for social and religious instruction. Through storytelling, communities reinforced:

- Respect for family and lineage

- Observance of ritual and sacramental duties

- Caution regarding the supernatural and wilderness

- Awareness of social and moral consequences

While modern audiences may see the Lobisón as merely a werewolf tale, traditional oral accounts integrate it with cosmology, morality, and social cohesion, reflecting a deeply rooted Iberian worldview.

Author’s Note

The Lobisón is a compelling example of folklore as moral and social mirror. It demonstrates how human fears, of sin, misfortune, wilderness, and inherited curses, are expressed through supernatural imagery. By blending wolf and human characteristics, the Lobisón embodies the liminal space between civilization and nature, obedience and transgression. Reading these stories helps us understand rural Iberian perspectives on family, morality, and the night-bound dangers of the world beyond the village.

Knowledge Check (Q&A)

- Q: Which Spanish regions are most associated with the Lobisón?

A: Asturias and Galicia. - Q: What triggers transformation into a Lobisón?

A: Family curses, ritual breaches, seventh son birth, or witchcraft. - Q: How is the Lobisón typically described in wolf form?

A: Large wolf-like creature, sometimes with glowing eyes or partial human features. - Q: What protective measures did villagers use?

A: Holy water, prayers, silver, trained dogs, or ritual hunts. - Q: Which folklorist or collection documents the Lobisón?

A: 19th-century Asturian and Galician ethnographers; public-domain folklore anthologies. - Q: What moral concepts does the Lobisón symbolize?

A: Consequences of sin, failure to observe ritual, family neglect, and vulnerability to supernatural forces.

Source: 19th-century Asturian and Galician ethnographic collections; public-domain Spanish folklore anthologies

Origin: Spain; northern regions (Asturias, Galicia); rural oral culture from pre-modern through 19th century, rooted in Catholic and Celtic-influenced folk traditions.