Makahiki is an ancient Hawaiian festival dedicated to Lono, the god of agriculture, rain, fertility, and peace. Celebrated for roughly four lunar months during the wet season, it marked the Hawaiian New Year. The festival’s timing followed the rising of the Pleiades in the evening sky, a celestial sign that the season of rest and renewal had arrived. Makahiki signaled a dramatic shift in daily life. Warfare was strictly kapu (forbidden), labor eased, tribute offerings were presented, athletic games flourished, and chiefs led ceremonies meant to strengthen the bond between gods, land, and people. The festival varied from island to island, yet all communities upheld its core purpose: honouring Lono and renewing the spiritual contract between Hawaiians and the natural world.

Description

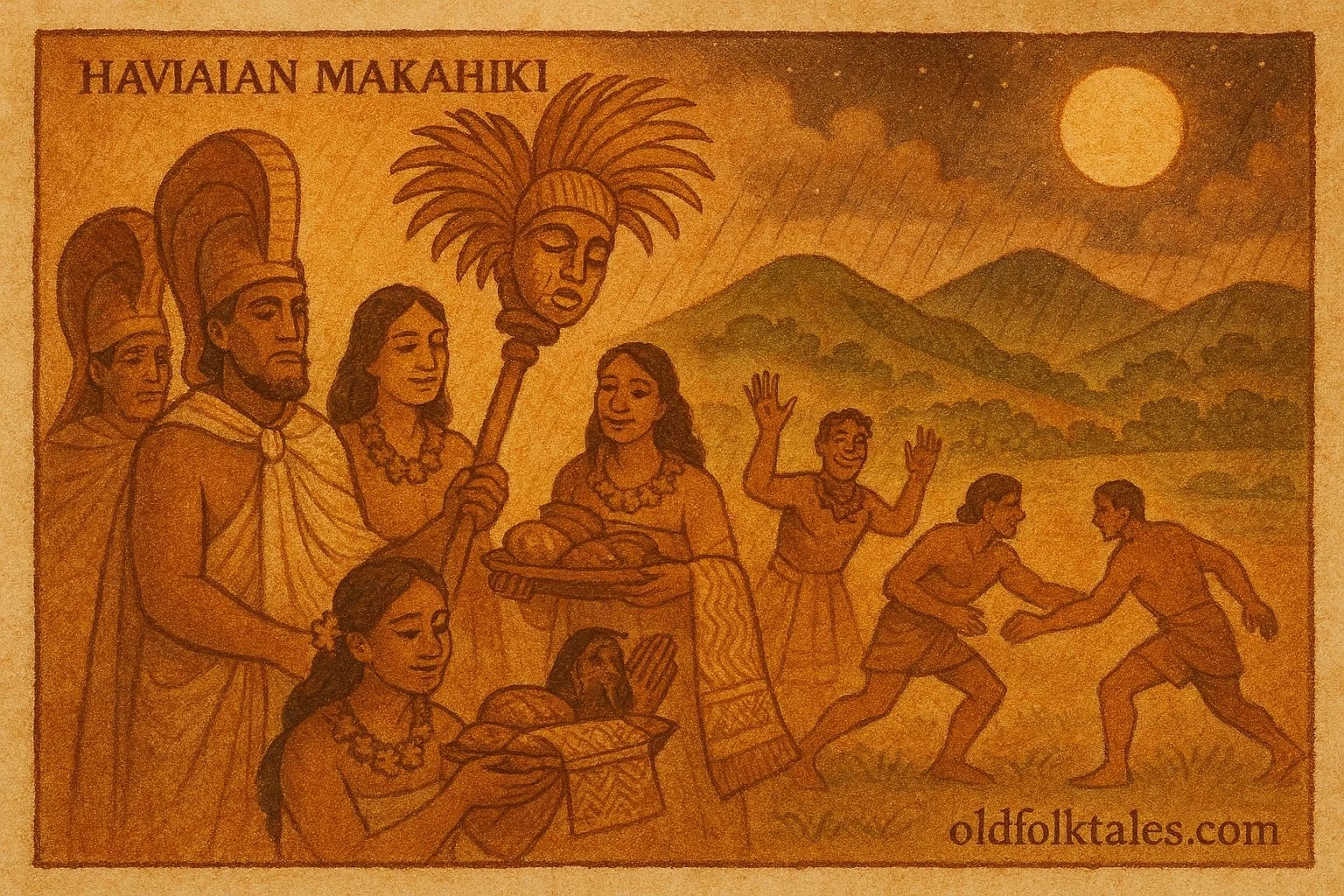

Makahiki unfolded in carefully structured phases. The festival traditionally began when the rising Pleiades coincided with the new moon, a moment believed to open the year’s sacred season. The first major event was the appearance of the Akua Loa, a tall staff or carved figure representing Lono, bedecked with white kapa cloth, feathers, and symbolic emblems. Priests and attendants carried the Akua Loa around the island, following traditional routes across districts. Communities greeted its arrival with chants, offerings, and gestures of reverence, for Lono was believed to be physically present through this ritual presence.

Central to Makahiki was peace. Battles, political conflicts, and aggressive acts were suspended. This peaceful restriction was not merely symbolic; it reflected the belief that Lono’s season brought growth, rain, and life. To shed blood during Makahiki would disrupt that delicate balance. Instead, communities focused on replenishing themselves. Farmers rested their fields, fishermen let their fishing grounds recover, and chiefs allowed their people a rhythm of ease that contrasted with the busy cycles of the rest of the year.

Offerings known as hoʻokupu played a major role. People presented foods such as taro, sweet potatoes, pigs, kapa cloth, and crafted goods. These offerings reaffirmed a reciprocal relationship, the people honoured Lono, and in return, Lono sustained the islands. Chiefs accepted these offerings on behalf of the god, reinforcing their spiritual role within society.

Makahiki was also a time of sport, skill, and joy. Hawaiians participated in games such as ʻulumaika (stone disk rolling), kōnane (a strategic board game), haka moa (a one-legged wrestling match), boxing, surfing contests, and foot races across villages. These competitions trained the body, entertained the community, and bridged the divide between seriousness and celebration.

Music and dance infused the season. Hula, chanted poetry, and drum rhythms honoured the cycles of rain and growth associated with Lono. Because Makahiki was a time free of war, cultural expression flourished in ways that highlighted unity and thanksgiving. Priests performed rites asking for abundant harvests, favourable rainfall, and the protection of the islands.

As the festival neared its end, a symbolic test of the chief marked the transition back to the everyday world. In some traditions, warriors threw spears at the chief, who was expected to deflect them. His success symbolized his worthiness to guide the people in the year ahead. When the Akua Loa returned to its resting place, the kapu on war lifted. Life returned to its normal rhythm, but the blessings of Makahiki were believed to set the tone for the entire year.

Mythic Connection

Makahiki is inseparable from the mythic identity of Lono, one of Hawaiʻi’s principal gods. Associated with gentle rains, cloud forms, agricultural abundance, and peace, Lono’s influence mirrored the wet season that sustained the islands. His mythology describes him as a deity who nurtures the land and brings prosperity. Thus, Makahiki became a ritual reenactment of the world under Lono’s care.

The season also reflects deeper Hawaiian cosmology. Life was understood as a cycle in which work, rest, war, and peace each had their rightful place. Makahiki represented a cosmic pause, a moment when the destructive potential of human activity was deliberately restrained. By prohibiting war, Hawaiians acknowledged that the land needed time to recover. This mirrored the agricultural rest that enriched soil fertility.

The Akua Loa procession itself is mythic in tone. It embodies the idea that gods travel through the land, witnessing the state of human affairs and blessing communities. Each district’s greeting of Lono renewed the connection between people and the divine. The carved staff became a living symbol of divine presence, a portable shrine linking heaven, earth, and human obligation.

In addition, the alignment with the Pleiades tied Makahiki to the sky. Hawaiian experts of navigation and agriculture used such celestial markers to regulate ritual time. The stars therefore played an active role in the mythic rhythm of the year.

Modern revivals of Makahiki continue to emphasize this spiritual connection. The festival remains a reminder that Hawaiʻi’s cultural roots honour balance, environmental stewardship, and respect for divine order.

Author’s Note

This account of Makahiki traces the festival’s harmony between human rest and divine blessing. Its rituals illuminate Hawaiʻi’s belief in cycles, celestial order, and the living presence of Lono. The festival continues to serve as a cultural anchor, reminding Hawaiians of their relationship with land, ancestors, and gods.

Knowledge Check

1. What deity is Makahiki dedicated to?

Lono, the Hawaiian god of agriculture, rain, fertility, and peace.

2. How long does Makahiki typically last?

About four lunar months during the wet season.

3. What major activity becomes kapu during Makahiki?

Warfare — violence is forbidden as a sign of respect for Lono.

4. What offering tradition plays a central role?

Hoʻokupu, the giving of food, crafts, and goods to honour Lono.

5. What symbol of Lono is carried across districts?

The Akua Loa, a carved and decorated staff embodying the god.

6. Why was athletic competition important during Makahiki?

It strengthened community bonds, tested skill, and celebrated renewal during the peaceful season.