Moʻo (pronounced moh-oh) are a class of potent reptilian and shapeshifting beings deeply embedded in Hawaiian cosmology and oral tradition. They function both as guardians and enforcers of sacred natural spaces such as freshwater pools (wai), fishponds (loko iʻa), and ʻawa (kava) gardens. Their role bridges the spiritual, political, and ecological realms, making them central to Hawaiian conceptions of mana, ancestry, and place-based stewardship.

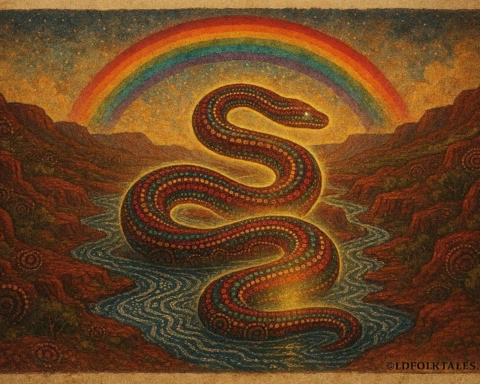

Moʻo are usually described as large, serpentine or lizard-like creatures, sometimes scaled, sometimes smooth-skinned, and often with shimmering, iridescent bodies reflecting the water they inhabit. In some accounts, they can grow to immense sizes, stretching along stream beds or ponds, while others depict smaller, almost human-sized forms that can move silently along water edges. They are frequently associated with shapeshifting, appearing in human form to interact with chiefs, villagers, or travelers, and sometimes to teach lessons, enforce kapu (sacred restrictions), or protect a territory.

Relive the heroic sagas of every age – stories of triumph, tragedy, and timeless valor

Appearance

The physical portrayal of moʻo is flexible but consistently reptilian or serpentine:

- Primary form: Lizard, dragon, or serpentine water creature, often massive, with glittering scales, webbed claws, and glistening eyes reflecting the sky or the stars.

- Shapeshifted form: Human or chiefly figure, maintaining subtle reptilian traits such as scaled fingertips, slitted eyes, or a greenish hue.

- Environmental blending: Moʻo can meld into ponds, rocks, or vegetation, rendering them nearly invisible to casual observers. Some accounts note that their eyes glow at night, and their movement generates ripples or fog over water.

These beings are not “monsters” in a purely negative sense: many moʻo are guardian ancestors, their form designed to inspire awe and respect.

Powers and Abilities

Moʻo possess a rich array of supernatural abilities linked to their guardianship of water and land:

- Shapeshifting: Ability to move between lizard, serpent, and human forms. Some accounts describe moʻo adopting animal companions or controlling other creatures.

- Water manipulation: Moʻo can stir ponds, streams, or waterfalls; they influence tides, currents, and fish abundance, reflecting their role as ecological regulators.

- Mana amplification: Some moʻo embody the mana of prominent ancestors or deified chiefs. Their presence amplifies the spiritual potency of a site and can either bless or punish human activities.

- Territorial enforcement: Disrespecting sacred spaces, polluting water, or violating kapu may provoke moʻo to send storms, sickness, or misfortune.

- Prophetic knowledge: In certain chants and mele, moʻo are linked to foreknowledge or prophecy, guiding chiefs in decision-making and community stewardship.

Behavior and Mythic Roles

Moʻo narratives vary across the islands but share key motifs:

- Guardianship: Many moʻo are described as protecting freshwater pools and fishponds. Local families and villages often recount how a moʻo inhabits a pond to safeguard the resources, especially fish and vegetation, ensuring that human use remains sustainable.

- Ancestor embodiment: Some moʻo are deified chiefs, linking genealogy to physical space. In these cases, the moʻo functions as both a spiritual guardian and a literal familial ancestor, ensuring that land and water rights respect lineage obligations.

- Punishment and morality: Moʻo enforce kapu, punishing trespassers or violators of sacred protocols. For example, a moʻo might capsize a canoe if its waters are desecrated or withhold fish from over-harvesting communities.

- Instruction and revelation: Some stories depict moʻo appearing to chiefs or commoners in human form, imparting wisdom, warning of natural or social danger, or offering healing knowledge.

The canonical motif describes moʻo as intimately tied to place. Beckwith, Fornander, and Malo recount numerous narratives linking specific moʻo to ponds, streams, or coastal sites. In these stories, a community’s well-being is directly connected to the moʻo’s satisfaction and protection.

Canonical Myth Example

In one Fornander collection, a moʻo inhabits a freshwater pond used by the local chief’s family. When outsiders attempt to fish without permission, the moʻo rises from the water in a lizard form, its scales flashing in the sunlight. Villagers witness ripples transforming into miniature waves that toss canoes or create sudden storms, demonstrating the moʻo’s control over the aquatic environment. Once the chief and family offer proper respect and hoʻokupu (gifts or rituals), the moʻo resumes its guardian role, and the waters calm.

Another common narrative portrays a moʻo transforming into a human, advising a chief on the construction of a fishpond, teaching engineering techniques, or warning of overfishing consequences. Here, the moʻo embodies ecological knowledge embedded within ancestral memory.

Cultural Role and Symbolism

Moʻo operate as a nexus of ecological, moral, and genealogical guidance:

- Kapu enforcement: Moʻo embody sacred restrictions on water, food, and land, reflecting Hawaiian notions of balance between humans and environment.

- Kaitiaki of water and food resources: Moʻo maintain the abundance of freshwater, fishponds, and irrigated gardens.

- Ancestral continuity: By personifying deified ancestors or important chiefs, moʻo remind communities of genealogical obligations and social cohesion.

- Moral and ethical exemplars: Tales warn against disrespect, overexploitation, or disregard for communal norms.

Through these roles, moʻo symbolize interconnectedness of humans, ancestors, and the natural world. Their presence in myths reflects deep Hawaiian ecological knowledge, including sustainable aquaculture, riparian stewardship, and respect for sacred spaces.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This entry is based on Hawaiian primary sources, chants, genealogical narratives, and early ethnographies, including Fornander, Beckwith, and David Malo. Interpretations emphasize historical context, island-specific variants, and the ethical-mythical roles of moʻo, avoiding modern tourist or fictional adaptations. Hawaiian terms like kaitiaki, kapu, and mana are preserved to retain cultural meaning.

KNOWLEDGE CHECK (Q&A)

- What form do moʻo usually take?

Reptilian, serpentine, or lizard-like, sometimes shapeshifting into human form. - What areas do moʻo traditionally guard?

Freshwater pools, fishponds, ʻawa gardens, and other sacred sites. - How do moʻo enforce morality or kapu?

Through storms, sickness, or direct action in the water when rules are broken. - Can moʻo appear as humans?

Yes, often to advise chiefs, instruct on rituals, or interact with villagers. - What Hawaiian concepts do moʻo embody?

Mana (spiritual power), kaitiaki (guardianship), and genealogical continuity. - Why are moʻo important in ecological understanding?

They symbolize stewardship of water and resources, teaching sustainable use and respect for sacred natural sites.

Source: Beckwith, Martha W.; Fornander Collections; David Malo; Bishop Museum archives

Origin: Hawaiian Islands; pre-contact oral tradition, recorded 19th–early 20th century