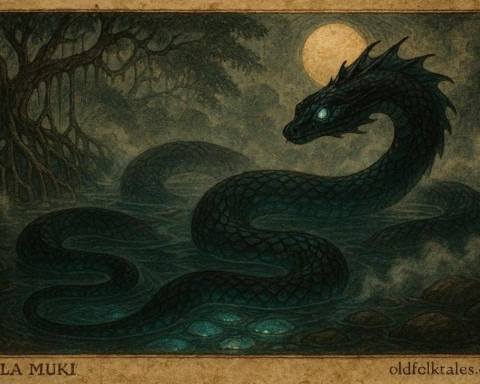

In the mythic imagination of South and Southeast Asia, the Nāga (Sanskrit: नाग) are serpentine beings of immense power, beauty, and mystery, beings who live both beneath the earth and within the waters. They are often portrayed as semi-divine serpents or human–serpent hybrids, with dazzling scales, jeweled hoods, and eyes that gleam like molten gold. In sacred art, they are crowned with multi-headed cobra hoods (often seven or nine), symbolizing their sovereignty over water and the underworld.

According to the Mahābhārata, Nāga is the offspring of Kadru (the mother of serpents) and Kashyapa, the ancient sage. Their brethren include Garuda, the eagle of Vishnu, who becomes both their adversary and divine counterpart. This mythic enmity, serpent versus bird, mirrors the natural tension between earth and sky, hidden depth and radiant height.

Relive the heroic sagas of every age – stories of triumph, tragedy, and timeless valor

One celebrated episode recounts the burning of the Khandava Forest, where the Nāga King Takṣaka plays a central role in the struggle between the human hero Arjuna, the god Agni, and the celestial order. In Buddhist literature, particularly the Jātaka Tales, Nāga appear as protectors and converts: Mucalinda, the Nāga King, shelters the Buddha beneath his coils during a storm after enlightenment, a gesture of divine submission to truth and compassion.

The Nāga’ domain is Pātāla, a luminous underworld filled not with fire, but with radiant jewels and flowing rivers. There they guard amṛta (nectar of immortality) and cosmic treasures, but they also rise to the surface to influence rainfall, fertility, and even royal fortune. Temples across India and Southeast Asia, from the carvings of Angkor Wat to the Nāga balustrades of Thailand, immortalize their serpentine majesty as guardians of sacred thresholds.

Yet, Nāga is not purely benevolent. When angered or dishonored, they unleash droughts or floods. Ritual offerings of milk, rice, or jewels are made to appease them, echoing the agricultural dependency of early civilizations upon seasonal waters. Thus, the Nāga is both protector and peril, a symbol of the ambivalence of nature itself.

Quoted excerpt:

“The Nāga King who dwells in the netherworld (Pātāla) rises to grant boons.” Mahābhārata, Ganguli translation (1883–1896)

Cultural Role

The Nāga symbolizes a triad of natural, spiritual, and moral principles:

- Nature’s fertility and power: water, rain, and the serpentine flow of rivers.

- Spiritual guardianship: protectors of Dharma, keepers of sacred treasures.

- Moral ambivalence: a reminder that even divine forces can bless or curse, depending on human virtue.

In Hinduism, Nāga is associated with Viṣṇu (who rests upon the cosmic serpent Śeṣa) and Śiva (who wears serpents as ornaments). Śeṣa himself is the eternal serpent upon whom the universe rests, each coil symbolizing cyclical time.

In Buddhism, Nāga embody devotion: their transformation under the Buddha’s compassion reveals the triumph of enlightenment over primal nature.

In Southeast Asia, Nāga was absorbed into local mythic systems. In Khmer and Thai lore, they are river dragons and founding ancestors, the Nāga princess who marries an early Khmer prince is said to have birthed the royal line of Cambodia.

In ritual life, Nāga Panchami, a Hindu festival celebrated across India and Nepal, venerates serpents through offerings of milk and prayers. It is believed that honoring Nāga ensures good rainfall and protection from snakebite.

In art, Nāga serve as architectural guardians, their coiled forms frame temple entrances, symbolizing the threshold between the earthly and divine. Their bodies, carved as balustrades, echo the mythic Churning of the Ocean of Milk, where gods and demons used a Nāga as the cosmic rope to create the elixir of life.

The Nāga, thus, is not merely a serpent but a cosmic mediator, connecting earth, water, and heaven; mortals, spirits, and gods. To revere the Nāga is to respect the unseen forces that sustain creation.

Explore the mysterious creatures of legend, from guardians of the sacred to bringers of chaos

Author’s Note

As a researcher and storyteller, I find the Nāga one of the most enduring symbols of Asia’s mythic ecology, a living metaphor for balance between fear and reverence, power and compassion. From India’s rivers to the temples of Angkor, the Nāga’s image coils across continents, carrying within it the shared spiritual grammar of humanity’s dialogue with nature.

Knowledge Check (Q&A)

- What are Nāga primarily associated with in Hindu and Buddhist lore?

→ Water, fertility, and protection of sacred spaces. - Name one major Nāga King from the Mahābhārata.

→ Takṣaka. - In Buddhist lore, which Nāga shelters the Buddha during a storm?

→ Mucalinda. - What does the Nāga symbolize in Southeast Asian architecture?

→ Guardianship of thresholds between the human and divine. - Which festival honors Nāga in Hindu tradition?

→ Nāga Panchami. - What moral concept do Nāga embody?

→ The balance of nature’s blessings and dangers, benevolence through respect.

Source:

- Mahābhārata, trans. Kisari Mohan Ganguli (public domain, 1883–1896)

- The Jātaka Tales, ed. and trans. E. B. Cowell and T. W. Rhys Davids (public domain)

- Indian Serpent Lore: The Nāga in Hindu Legend and Art (archival monograph, Internet Archive)

Origin:

Vedic to Classical South Asia; later diffused throughout Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Indonesia).

Earliest mentions appear in the Ṛgveda, with elaborations in Puranic and Buddhist literature (3rd century BCE – 12th century CE).