Omizutori, known formally as Shunie, is one of Japan’s oldest surviving Buddhist rituals. Established in 752 CE at Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, it forms part of a two-week ceremony marking both repentance and the coming of spring. The event occurs annually at Nigatsu-dō Hall, a sacred sub-temple within Tōdai-ji. Rooted in the ancient Buddhist calendar, Omizutori is celebrated each year from March 1 to 14, continuing a lineage of over twelve centuries without interruption, making it one of Japan’s longest-running religious traditions.

The ritual’s origin lies in Buddhist legends and the belief in cleansing one’s sins to renew both the body and the community before spring planting. Although associated with Buddhism, the ritual also reflects Japan’s syncretic spiritual culture, where Shintō nature reverence blends harmoniously with Buddhist moral philosophy.

Description

Omizutori literally means “water-drawing.” The term refers to the climactic ceremony on the night of March 12, when monks draw sacred water from a nearby well called Wakasa-no-Yusui, believed to flow only once a year. This water is offered to Kannon Bosatsu, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and shared symbolically with the faithful for blessings and longevity.

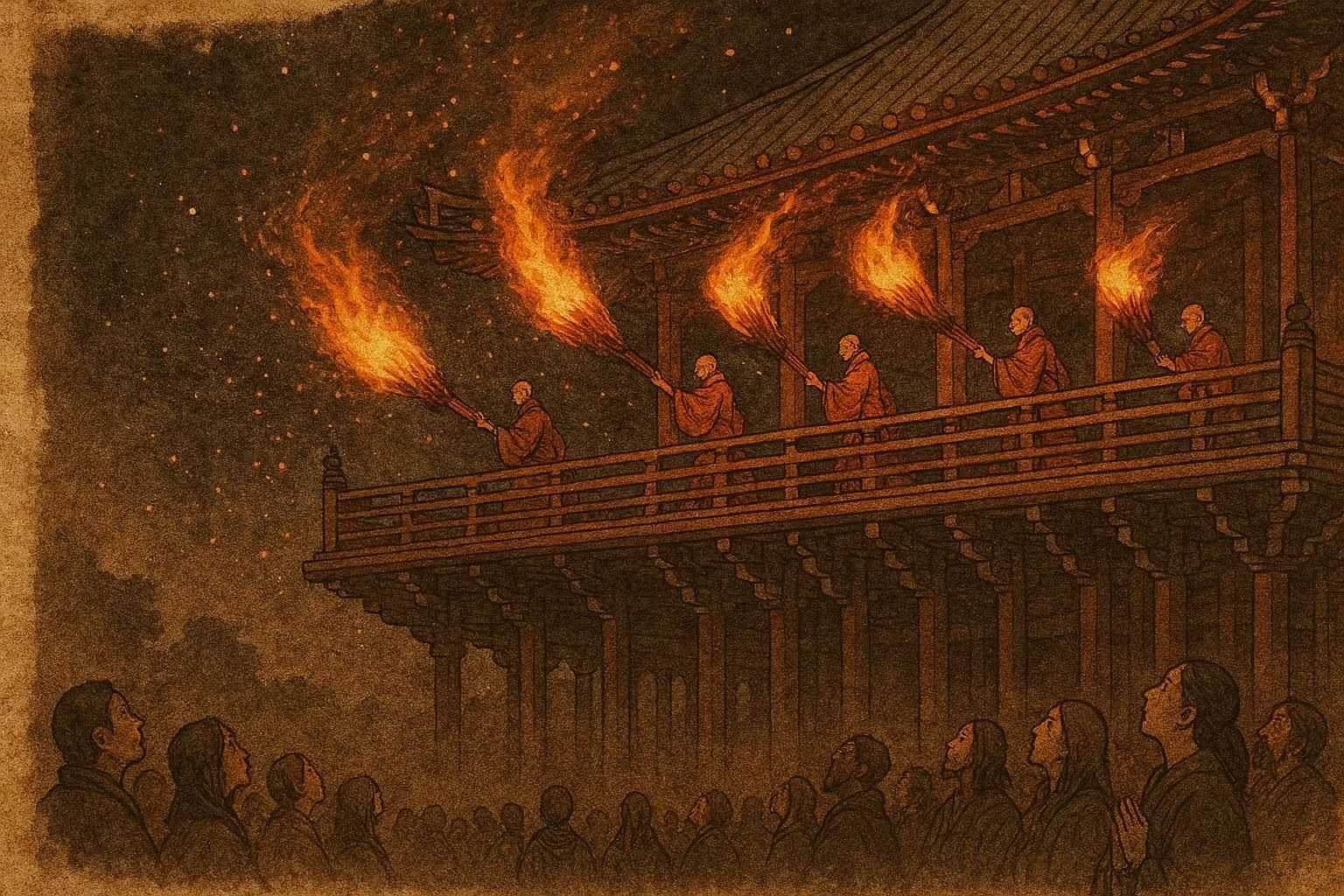

Throughout the festival, priests perform nightly rites within the temple halls. They offer prayers, chant sutras, and present incense to atone for humanity’s sins. The ceremony’s most iconic feature, however, is the Otaimatsu, or torch ceremony, performed on the balcony of Nigatsu-dō. Massive pine torches, some over six metres long, are carried by monks who run along the balcony, scattering sparks over the gathered crowd below. These sparks are said to purify the onlookers and bring good fortune for the coming year.

The entire event unfolds over fourteen days of ritual progression:

-

The first week is dedicated to preparation, fasting, and purification.

-

The second week brings public prayers and processions, culminating in the water-drawing rite.

-

The final night, called Nehan-e, marks spiritual completion, the cleansing of karmic burdens and the welcoming of spring’s light.

What makes Omizutori remarkable is its continuity of performance. The same gestures, chants, and fire-bearing sequences have been preserved since the 8th century, passed down through generations of monks at Tōdai-ji. The event draws thousands of visitors annually, who gather not only for religious devotion but also to witness a profound living tradition that fuses spectacle with sanctity.

Mythic Connection

According to temple lore, the ritual was first performed by the monk Jitchū, a disciple of the revered priest Rōben, Tōdai-ji’s founder. The story recounts that Jitchū invited eleven water-drawing deities (Jūichimen Kannon) from across Japan to attend the ceremony. When one deity arrived late, he purified himself by drawing water from the Wakasa well and offering it to Kannon, giving rise to the name Omizutori (“drawing of the sacred water”).

In Buddhist cosmology, water represents the essence of compassion and rebirth, while fire embodies enlightenment’s purifying power. The twin elements, the glowing torches and the hidden sacred spring, symbolise spiritual balance: light burns away ignorance, and water renews life. The ritual, therefore, is not merely a temple festival but a reenactment of cosmic purification, aligning the human and natural worlds at the threshold of a new season.

Shintō influence can also be traced in its timing and reverence for natural elements. Spring’s arrival marks the agricultural renewal essential to early Japanese life. By cleansing the spirit before planting season, communities sought to ensure divine favour for crops and harmony between people, earth, and kami (spirits).

Over time, Omizutori came to represent both personal and communal salvation, repentance not just for oneself but on behalf of the nation. Its endurance through wars, fires, and political shifts testifies to Japan’s cultural dedication to ritual continuity as a sacred duty.

Cultural Continuity and Modern Meaning

Today, Omizutori remains one of Nara’s most important annual events. Despite Japan’s modernization, the ritual’s spiritual meaning endures. Tourists, locals, and monks alike gather beneath Nigatsu-dō’s wooden eaves to feel the warmth of the torches and hear the rhythmic chanting echoing through the night air. Television coverage and academic studies by institutions such as Kokugakuin University Museum and the Nara National Museum have deepened appreciation for its role as intangible cultural heritage.

In the modern context, Omizutori stands as a meditation on environmental harmony, ethical renewal, and cultural memory. The ritual teaches that purification and repentance are not acts of fear but of gratitude, an acknowledgment of one’s place within the greater order of life. Through the merging of Buddhist compassion and Shintō reverence for nature, the ceremony continues to express a timeless truth: that renewal is possible when humans approach the sacred with humility and light.

Author’s Note

The Omizutori ceremony embodies Japan’s spiritual resilience and unity between nature, ritual, and faith. Across more than twelve centuries, this water-drawing rite has preserved a delicate balance between Buddhist devotion and seasonal celebration. It stands not merely as a temple festival but as a living bridge between past and present, where the flames of compassion and the waters of rebirth continue to purify the soul of a nation.

Knowledge Check

-

What does “Omizutori” mean?

It translates to “water-drawing,” referring to the sacred collection of spring water offered to Kannon. -

Where and when is the ritual held?

At Nigatsu-dō, Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, Japan, from March 1–14 each year. -

Who is the main deity honoured during the ceremony?

The Bodhisattva Kannon, symbol of compassion and mercy. -

What is the purpose of the torch ceremony?

The flames purify the crowd and bring blessings for the coming year. -

Who founded the Omizutori ritual?

The monk Jitchū, disciple of Rōben, the temple’s founder. -

Why is Omizutori significant in modern Japan?

It symbolizes cultural continuity, environmental respect, and spiritual renewal.