Pania of the Reef, known in Māori tradition as Pānia o te Rēhi, is one of the most beloved figures of Ngāti Kahungunu oral history. Her story intertwines the natural world, the spiritual realm, and the emotional tensions of love between human and non-human beings, a theme deeply seated in Polynesian mythic structures. Though often called a “sea-maiden,” her nature varies across iwi retellings: sometimes she is close to a taniwha, sometimes one of the patupaiarehe (supernatural forest or coastal beings), and sometimes a unique guardian spirit connected to the reef off modern-day Napier.

Descriptions of Pania consistently stress extraordinary beauty, but it is sea-beauty, not human glamour: luminous eyes reflecting moonlit water, long dark hair that moves like waves, skin said to glisten with fine spray from the ocean, and a voice soft enough to resemble the surf meeting the shore. Her movements are fluid, controlled, and graceful; many elder tellers describe her as a being who seems more grown from the sea than living beside it.

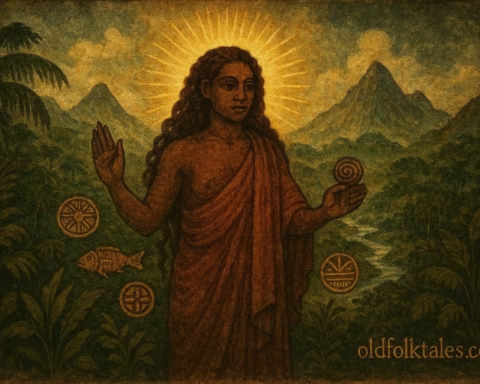

Discover the gods, goddesses, and divine spirits who ruled the heavens and shaped human fate

Pania is also described as someone who appears almost human when she emerges from the water, but with subtle signs of the sea’s claim upon her: coolness of touch, the faint scent of salt, and an ease in darkness that humans lack. In the sea, she moves as effortlessly as a dolphin or kahawai fish, able to dive, glide, and return to the reef with the same speed and certainty as other ocean-dwellers.

Powers and Attributes

Pania’s nature grants her a cluster of abilities common to powerful Māori water-beings:

- Amphibious life: She moves freely between sea and land, though land-bound life diminishes her strength.

- Night-travel: She emerges only at night, protected by tapu and the mana of the reef.

- Shape-associated identity: She is tied intrinsically to the reef, able to sense disturbances, dangers, or changes in the ocean’s mood.

- Protective influence: As a guardian, she watches over the coastal waters and those who respect them.

- Transformation: Central to the tale is her ultimate metamorphosis into the reef itself, a living act of self-sacrifice, guardianship, and permanence.

Her powers are always linked to place and to kaitiakitanga, the Māori ethic of guardianship. Pania is not a generalized fairy or mermaid figure; she is anchored to Heretaunga, its genealogies, and its coastline.

Core Myth

Most Ngāti Kahungunu versions share a similar narrative shape:

Pania emerged each night from the reef, traveling through the waters to the shore under the cover of darkness. There she met a young chief’s son, in many versions named Karitoki, who fell deeply in love with her. Their meetings were secret, quiet, and wrapped in the silver glow of the moon. The young man wanted Pania to remain with him always, to live as his wife on land.

But Pania could not. The sunlight would weaken or destroy her; her home was the world beneath the waves, among her sea-kin. The lovers’ meetings had to remain nocturnal and fleeting.

In some versions, the young man attempted to bind her to the human world by placing cooked food to her lips before dawn. The act was profoundly tapu-breaking, cooked food can strip supernatural beings of mana or force them into human form, but it failed. Pania sensed the betrayal, fled to the sea, and was never able to return to human shape.

In others, she left not because of betrayal but because the sea called her home with irresistible force. She returned to her people underwater, mournful but obedient to her nature.

Whichever version is told, the ending remains the same:

Pania transformed into the reef, stretching from the base of the cliffs into the ocean. From that moment onward, her presence would guard the bay, watch over her descendants, and protect the coastline from dangers, natural and supernatural alike.

The reef is not simply stone but a manifestation of enduring love, sorrow, duty, and guardianship. The Napier statue, slender, poised, and sea-swept, commemorates not only her beauty but her deep connection to land, sea, and lineage.

Behavior and Significance in Belief

Pania embodies the Māori worldview in which the natural environment is alive with genealogical relationships. She is not a monster, nor merely a victim: she is a kaitiaki, a protector who embodies the idea that landforms are ancestors and ancestors are part of the land.

Her behavior teaches:

- Respect for tapu: Violating sacred rules disrupts relationships between humans and the spiritual world.

- Consequences of desire without understanding: Karitoki loves her but attempts to make her something she is not, and loses her.

- The interdependence of people and place: Pania’s transformation is an affirmation that the environment is

- The power of water-beings: The sea is a realm of mana and danger, to be approached with reverence.

Cultural Role and Symbolism

Pania symbolizes the boundary between human and spiritual worlds, the delicate line that must not be crossed carelessly. In Māori cosmology, such boundaries maintain balance between tapu (sacredness) and noa (everyday life).

She is also a figure of:

- Love and sacrifice

- Guardianship and protection

- Identity tied to place

- The living spirit of the natural world

The reef is both her body and her enduring presence. It is a reminder that the land is not dead or inert; it breathes, remembers, and protects.

Explore the mysterious creatures of legend, from guardians of the sacred to bringers of chaos

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I based this entry on Ngāti Kahungunu sources, 20th-century local broadcasts (Papers Past), Māori ethnographic collections, and cross-checked retellings from iwi resources and museum archives. The story is an iwi-specific tradition, and I avoid blending it with tourist or fictional versions. Māori concepts such as tapu, kaitiaki, and mana have been preserved with respect to their cultural meaning.

KNOWLEDGE CHECK (Q&A)

- What supernatural nature is most commonly attributed to Pania?

A sea-maiden or sea-spirit tied to the reef at Napier. - Why did Pania only visit the shore at night?

Sunlight weakened her; nighttime protected her tapu nature. - What caused Pania to return to the sea permanently?

Either betrayal (attempt to bind her with cooked food) or the sea’s spiritual call. - Into what natural feature did Pania eventually transform?

She became the reef off Napier, acting as a guardian. - What cultural principle does Pania embody?

Kaitiakitanga,guardianship of land and sea. - What lesson does the story teach about human desire?

Love must respect identity; forcing change breaks sacred balance.

Source: Ngāti Kahungunu oral tradition; 1954 broadcast transcript (Papers Past); regional histories; Napier archives

Origin: Aotearoa New Zealand; Hawke’s Bay / Heretaunga (Ngāti Kahungunu)