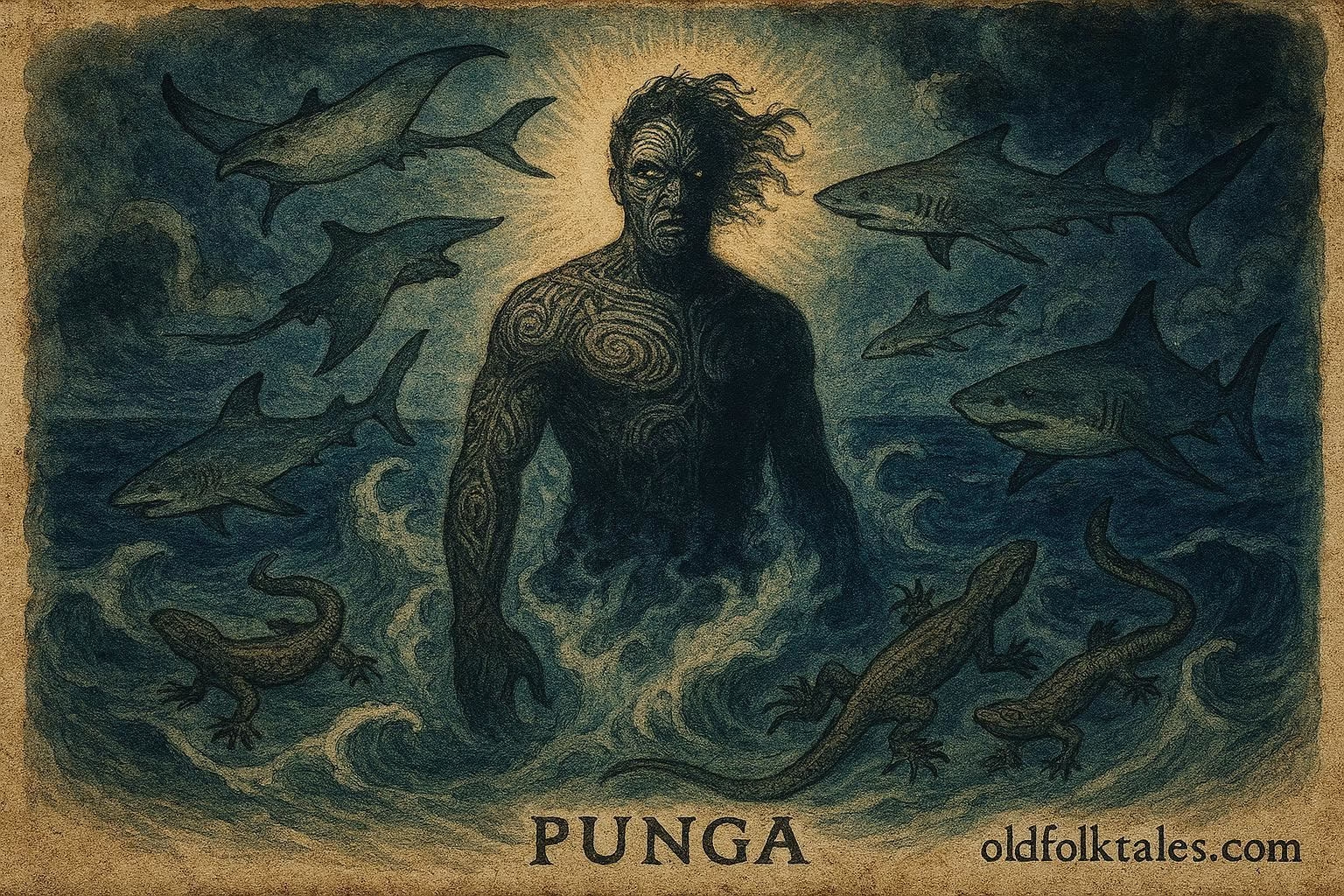

In the vast genealogical universe of Māori cosmology, Punga stands as a distinctive ancestral figure: the progenitor of the world’s “ugly,” fearsome, or uncanny creatures, particularly sharks, rays, lizards, and other beings that provoke awe or dread. He is remembered not simply as a mythical monster-maker but as a pivot point in the great whakapapa (genealogical sequences) that structure Māori understandings of creation, kinship, and the moral placement of beings within the natural world. Punga’s story is woven deep into the pre-human epochs, when gods, cosmic forces, and sentient animal-beings shaped the environment.

Punga is the son of Tangaroa, the great deity of the sea. Tangaroa’s numerous children embody a wide array of marine life, but Punga’s offspring in particular represent the more unsettling, mysterious, and powerful creatures that dwell in shadowed waters. These include the taniwha-like sharks that guard coasts, the rays that glide like living shadows across the seabed, and reptiles whose stillness and sudden motion carry an aura of mana and danger.

Discover the ceremonies and sacred festivals that honored gods and balanced nature’s powers

The traditional genealogies portray Punga not as malicious but as marked by a certain otherness, a liminal quality that places him between worlds. His descendants frequently inhabit places that demand caution or ritual respect: deep pools (wai kino), reefs, rocky headlands, the dark edges of forests, and underwater caves. In this sense, Punga symbolizes the realm of beings that inspire fear because they dwell beyond ordinary human control. This reverence for the unknown is foundational in Māori cosmology, where every creature, even frightening ones, has a rightful place, ancestry, and role.

Several iwi maintain stories in which Punga’s children flee from a primordial disturbance. In some narratives, after the great storms or after the conflicts among the gods, many of the sea-creatures scatter. Some travel into the deep ocean, others hide in inland waterways, and some take on new protective or antagonistic roles toward human communities. These tales place Punga at a crucial mythological juncture: the dispersal of species into patterns still recognizable today. In these stories, the fearsome appearance of sharks or the eerie, smooth gliding of rays is explained through their descent from a powerful ancestor whose lineage was shaped by cosmic upheaval.

Not every creature in Punga’s line is terrifying. Some traditions soften the term “ugly,” interpreting it instead as beings of unusual form, sacred danger, or transformative potential. In Māori cosmology, ugliness can be a mark of hidden prestige; deformation can signal primordial antiquity. Thus, Punga’s offspring are not moral villains but creatures with deep mana, whose forms teach lessons about respecting boundaries and understanding that beauty is not the only sign of worth.

One of Punga’s most prominent children is Ikaroa, sometimes associated with fish or with the Milky Way itself, indicating how Punga’s lineage spans both earthly waters and celestial pathways. Another is Tangaroa-a-kea, linked with sharks and other powerful marine animals. In some traditions, Punga’s descendants even include tukupā (supernatural marine guardians), beings who protect particular harbors or tribes. This diversity of offspring demonstrates that Punga is not simply a figure of monstrosity but a foundational ancestor whose lineage includes both danger and protection.

Because Māori genealogies are simultaneously cosmological and ecological, the figure of Punga provides an ordered explanation for creatures that humans find unsettling. Sharks are dangerous not because they are evil, but because they belong to a whakapapa characterized by power, autonomy, and the right to exert authority in their domains. Lizards, with their uncanny stillness, are linked to ancestral spiritual energies and are respected accordingly. Rays, often associated with hidden depths or the shadowed seafloor, fit well within Punga’s line of mysterious and potent beings.

In some iwi traditions, Punga also becomes a symbol of the unknown or the misunderstood. His association with creatures humans fear suggests a lesson: fear often arises from confronting a being whose mana exceeds your understanding. The proper response is not destruction but ritual respect, thoughtful engagement with place, and recognition that every creature carries genealogical dignity.

Punga’s appearance in genealogical recitations (whakapapa kōrero) during rituals, meetings, or educational settings is not merely symbolic. It reinforces a worldview where the natural world is kin, and where ancestry extends beyond humanity to fish, reptiles, birds, insects, and unseen denizens of sea and forest. By naming Punga as an ancestor, Māori speakers affirm a relationship between people and the creatures of the dangerous margins, a relationship of caution, humility, but also kinship.

In some traditions, Punga also stands as a metaphor for embodied difference, reinforcing cultural teachings about acceptance. Just as Punga’s children are diverse, often strange-looking, yet rightful members of creation, so too are human differences to be understood within whakapapa, not rejected. His myth anchors respect for creatures that might otherwise be feared or misunderstood, serving as a spiritual guide for ecological ethics.

Thus, Punga represents primordial diversity, the sacredness of the strange, and the rightful place of fearsome creatures within a balanced world.

Cultural Role

Ancestor of sharks, rays, reptiles, and other powerful or “fearsome” beings.

Symbol of dangerous places, deep water, reefs, caves, that require respect.

Embodiment of difference: beauty is not the measure of sacred worth.

Genealogical anchor connecting humans to the wider natural world through Tangaroa.

Cultural reminder to treat even frightening creatures as kin with mana.

Ecological model for respecting powerful species and their territories.

Explore the mysterious creatures of legend, from guardians of the sacred to bringers of chaos

Author’s Note

This entry synthesizes primary Māori genealogical sources and comparative Polynesian mythology to present Punga in a manner faithful to both the cultural context and the deep cosmological frameworks that structure Māori thought. No single printed version captures all regional variations; Punga lives within oral tradition, where each iwi shapes his role according to landscape, sea, and ancestral memory.

Knowledge Check

- Who is Punga’s father?

Tangaroa, the great deity of the sea. - What types of creatures descend from Punga?

Sharks, rays, lizards, and other powerful or uncanny beings. - Why are Punga’s descendants considered sacred?

They possess mana and occupy dangerous but important ecological spaces. - Does Punga represent evil?

No, he represents the unfamiliar, the potent, and the liminal. - How do Māori cosmologies view “ugly” creatures?

As beings with sacred ancestry, not moral inferiority. - What lesson does Punga’s mythology teach?

Respect the beings of dangerous places and acknowledge the dignity of difference.

Source: Māori oral tradition; Craig (Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology); Tregear (Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary)

Origin: Māori (Aotearoa New Zealand)