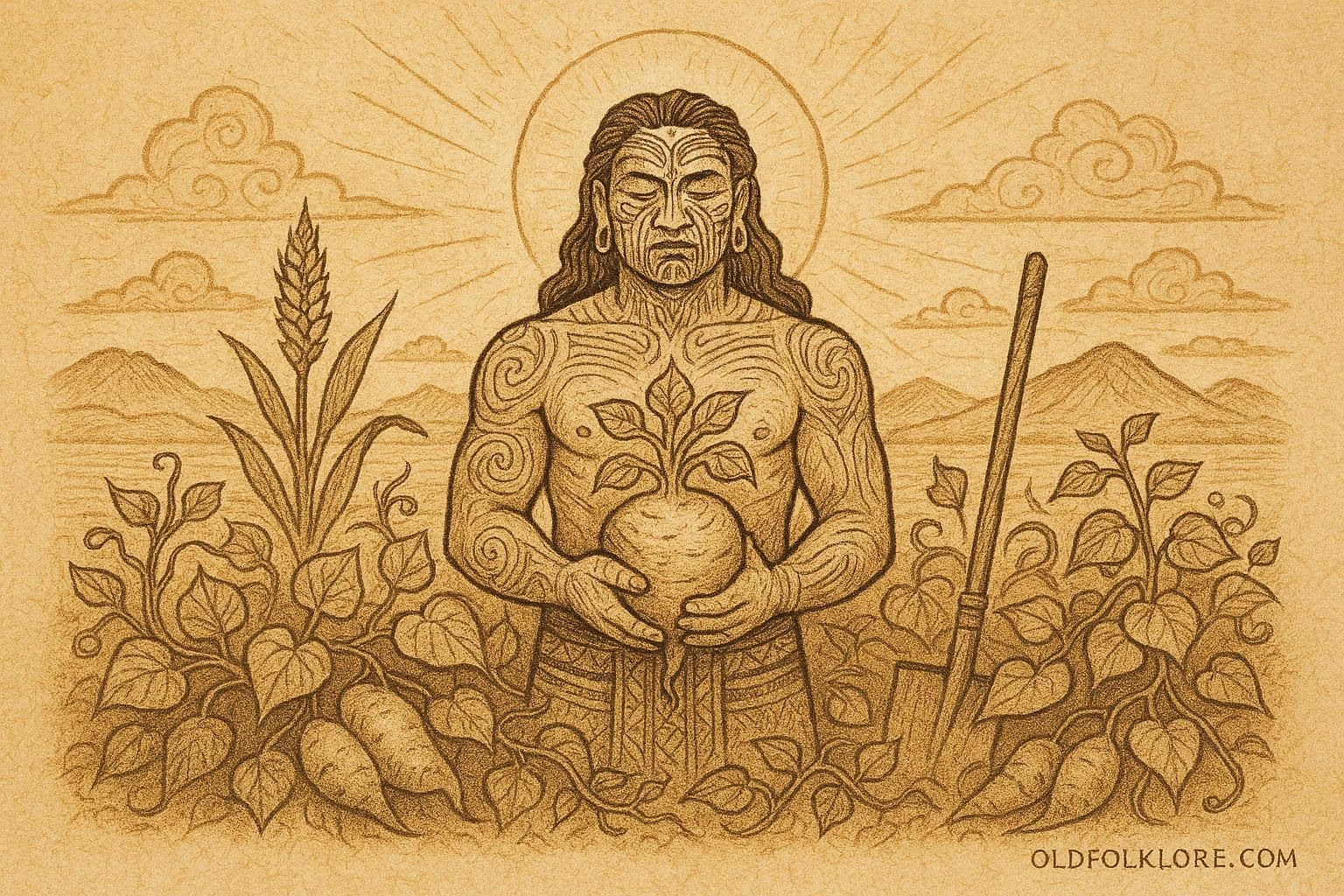

Rongo, sometimes called Rongo-mā-Tāne in extended genealogies, is the Māori atua (god) of cultivated crops, horticultural knowledge, and peaceful prosperity. He presides over kūmara (sweet potato), the most sacred of Māori staple foods, and is honored as the divine teacher who showed humanity how to plant, tend, and harvest crops with ritual care. While many of his brothers embody conflict, wild forests, tempestuous seas, or the dangers of the world, Rongo embodies the gentler side of creation, nourishment, settlement, and the enduring rhythm of cooperative life.

He is one of the children of Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother), born into the darkness that preceded light. Each brother shaped the world in different ways, but Rongo’s domain is the field, the space humans cultivate not only for survival but for community, ceremony, and harmony. He is invoked in agricultural rites, village peacekeeping, and seasonal festivals. His presence is felt in the hum of tilled earth, the smoke of offerings rising over gardens, and the shared meals that bind a people together.

Rongo’s sacred symbols include the kūmara vine, carved fertility motifs on food storehouses, earth ovens, and woven baskets for storing crops. Unlike warlike Tūmatauenga, Rongo’s spiritual authority encourages unity rather than division. Through him, the Māori link the cycles of growth with the deeper moral principle of living well with one another.

Mythic Story

In the age when the world was still young and the children of Rangi and Papa shaped the fate of the living, the land was both wondrous and dangerous. Forests overshadowed the plains, storms roared across the sea, and wild foods were plentiful yet unpredictable. Humanity lived close to the earth but without mastery over its rhythms. They gathered, they hunted, and they foraged, but they did not yet cultivate. They did not yet possess the knowledge of stability, of storing plenty for the seasons of want.

It was Rongo who changed this.

In the time following the dramatic separation of Sky and Earth, when the brothers quarreled about the future of creation, Rongo observed the turmoil with a quiet spirit. His brother Tūmatauenga prepared weapons. Tāwhirimātea summoned winds and storms. Tangaroa’s vast seas churned with restless might. Each atua took up an element of the world and stamped their nature upon it. But Rongo looked instead to the earth beneath them, the body of their mother, and the promise held in her soil.

Seeing the fragility of humanity caught between these divine powers, Rongo resolved to gift them something lasting: the art of cultivation, the knowledge that transforms survival into abundance and conflict into cooperation.

Māori tradition tells that the kūmara, the cherished sweet potato, was brought to Aotearoa through ancestral voyaging and through divine involvement. Some chants speak of Rongo residing in the upper realms, tending celestial gardens whose vines shone with soft, earthy light. Others say that the kūmara was his own sacred child, given to humankind so they might thrive. Whether through journeying or divine bestowal, the sacred root became the emblem of Rongo’s kindness, and the foundation of Māori horticulture.

But before gifting cultivation to mortals, Rongo first dealt with the family conflict among the atua themselves. While Tāwhirimātea’s storms battered forests and seas, Rongo sheltered quietly, waiting for the winds to pass. Tūmatauenga, the warrior brother, eventually rose against his siblings, subduing them and establishing humankind’s dominion over nature. But Rongo, unlike the others, did not resist Tūmatauenga. Instead, he accepted that the world required balance, that war and toil had their place, but so too must peace and sustenance.

After the storms and battles subsided, Rongo walked upon the earth to find humankind weary, hungry, and uncertain. Rivers had flooded. Forests had shifted. The world was new and unpredictable. Rongo approached them not with the thunder of an atua of war, but with the quiet assurance of a guardian of growth.

“Look to the earth,” he is said to have spoken through ritual prayers. “Within her lies the promise of life renewed.”

He instructed humanity in preparing the fields: clearing the land with reverence, softening the soil with rhythmic movements, and planting the first sacred vines with chants that connected the living to the atua. Each step was not merely agricultural, it was cosmological. Cultivation became a conversation with creation itself.

Under Rongo’s guidance, the people learned that crops grow not only through labor but through unity. Families worked together. Tribes coordinated seasonal efforts. Ritual offerings were made to acknowledge Rongo’s divine gift. Through these teachings, peace became woven into the rhythm of agricultural life. Where war scatters, planting gathers; where conflict divides, harvest unites hands and hearts.

Festivals arose to honor Rongo during planting seasons and again at harvest. Food storehouses were built with carved guardians invoking his protection. In these rituals, the community recognized that the earth responds best to harmony: disputes were settled before planting, and cooperative effort was praised as sacred conduct.

In some traditions, Rongo’s children are the creeping vines that spread across gardens, each shoot carrying his presence. To tend these vines was to honor him; to damage them carelessly was to neglect a divine gift. Even today, stories told on marae recount how the kūmara’s sweetness reflects Rongo’s gentle nature, a reminder that prosperity is a product of peace.

Thus, Rongo became not only the god of agriculture but also the atua of societal calm, the divine force that nurtured both the land and the bonds between people. Through him, the Māori came to understand that peace is not a passive state but an active cultivation, much like a garden: it must be planted, tended, protected, and shared.

Discover the gods, goddesses, and divine spirits who ruled the heavens and shaped human fate

Author’s Note

Rongo’s myth reminds us that the greatest forms of strength can be quiet ones. His gift of kūmara is more than food, it is the foundation of cooperation, patience, and shared prosperity. Through Rongo, Māori tradition teaches that peace is cultivated through deliberate action, thoughtful stewardship, and communal care.

Knowledge Check

Q1: What is Rongo the Māori god of?

A: Agriculture, cultivated crops, and peaceful prosperity.

Q2: What sacred food is especially associated with Rongo?

A: The kūmara (sweet potato).

Q3: How does Rongo differ from his brother Tūmatauenga?

A: Rongo embodies peace and cultivation, while Tūmatauenga represents war and conflict.

Q4: Why is cultivation significant in Rongo’s myth?

A: It transforms survival into stability and fosters cooperation among people.

Q5: What rituals honor Rongo?

A: Planting and harvest ceremonies, offerings, and carvings on food storehouses.

Q6: What theme does Rongo represent beyond agriculture?

A: Harmony and the moral value of communal effort.

Source: Māori Mythology, Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Source Origin: Aotearoa (New Zealand)