Songkran is Thailand’s traditional New Year celebration, observed each April during the solar transition into the rainy season. It draws from ancient Southeast Asian calendrical systems shaped by astronomy and agriculture. Over the centuries, Buddhist practice influenced the festival, blending cosmic timing with moral renewal. Songkran also shares cultural threads with water-based New Year festivals in neighboring regions, yet Thailand’s form of the celebration has developed a distinct identity shaped by Buddhist merit-making, community ties, and long-standing royal and village traditions.

Description

Songkran unfolds across several meaningful days, each tied to cleansing, gratitude, and the resetting of social relationships. The festival begins with preparation. Families clean their homes, refresh ancestral altars, and tend to images of the Buddha. This act clears physical and spiritual space, preparing households for the gentler rituals that follow.

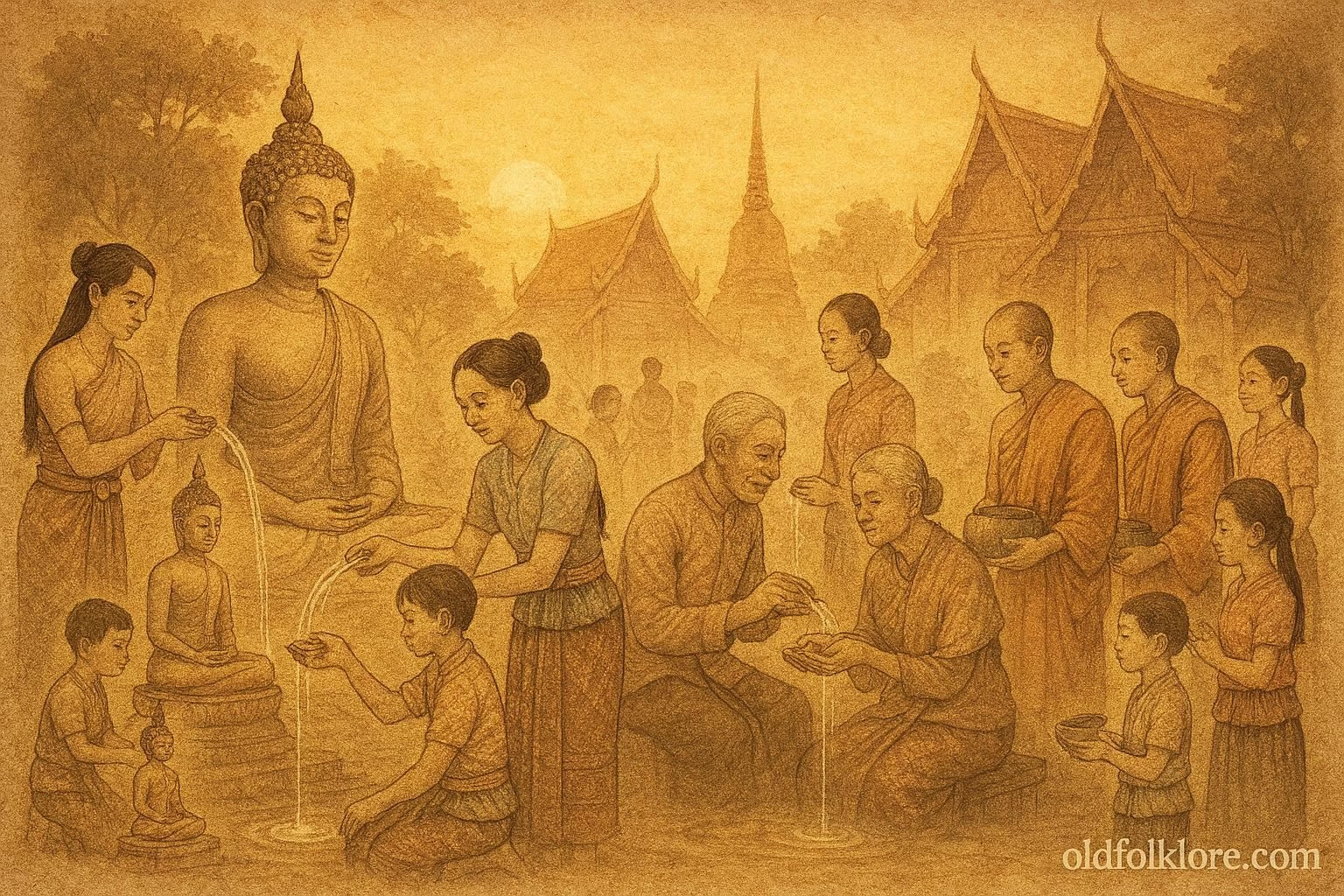

One of Songkran’s most symbolic practices is rot nam dam hua, the pouring of scented water over the hands of elders. Younger family members kneel, offer fragrant water in small bowls, and ask for blessings. The ritual expresses humility, respect, and continuity. Elders respond with prayers for well-being, harmony, and ethical living. Through this intimate exchange, families reaffirm their responsibilities to one another.

Temples become gathering points throughout the week. Many Thai families bring offerings of food, robes, and daily necessities to monks. These gifts build merit, a core Buddhist principle that connects ethical action to spiritual progress. Devotees also bathe Buddha statues with lightly poured water, symbolizing the washing away of past misdeeds. Unlike the lively street celebrations, these temple rites are calm, steady, and meditative.

In many areas, communities build sand stupas on temple grounds. They shape small towers of sand to symbolize the rebuilding of spiritual strength and the return of borrowed earth to sacred spaces. These stupas often glow with small flags and flowers. Each element reinforces the idea that renewal is both personal and communal.

Outside the temple environment, modern Songkran includes energetic public water-throwing. Streets fill with families, tourists, and groups of young people carrying buckets, water guns, and clay paste used for friendly blessings. Though playful, this custom has ancient roots. Water represents cleansing and good fortune, and the joyful atmosphere reflects the belief that renewal should be shared. The lightheartedness also relieves the heat of April, the hottest month in Thailand.

Rural areas maintain deeper traditional forms. Villagers may gather at riverside shrines, offer rice and flowers, and pray for rain as the agricultural season approaches. In these communities, Songkran blends Buddhist ethics with older animist understandings of the land. Water remains the central symbol across all variations: it purifies, heals, and prepares people for the year ahead.

Yet despite these different expressions, the heart of Songkran does not change. It is a ritual of cleansing, gratitude, and moral intention. Its endurance speaks to Thailand’s ability to honor ancient tradition while adapting to new social rhythms. Whether in quiet temples or lively streets, Songkran continues to remind participants that renewal begins with compassion, humility, and clear intention.

Mythic Connection

Songkran’s symbolism rests on a blend of Buddhist teachings and pre-Buddhist cosmology. Water acts as the central mythic bridge between the physical world and the moral order. In ancient Southeast Asian traditions, water marked boundaries, healed spiritual imbalance, and cleansed misfortune. It represented life’s cyclical return, reflecting the seasonal shift from extreme heat to the rains that sustain rice fields.

Buddhism later shaped these ideas through the language of karma and merit. The act of cleansing Buddha images echoes the washing away of defilements. Devotees symbolically participate in this purification, seeking clarity, mindfulness, and peace. Elders’ blessings reinforce the continuity of virtue, linking the new year with the Buddhist ideal of right conduct.

Some regional stories connect Songkran to mythical guardians of wisdom. A well-known tale tells of a celestial contest of riddles between a wise youth and a divine king. When the youth triumphed, the king’s daughters carried his severed head in an annual procession to prevent cosmic imbalance. Their movement became associated with the solar transition that marks Songkran. While symbolic rather than historical, the myth emphasizes the importance of knowledge, balance, and cosmic renewal at the start of the year.

Thus, Songkran unites agricultural cycles, Buddhist ethics, and mythic storytelling. Through water, offerings, and blessings, participants re-enter harmony with both the natural world and the moral universe. The festival becomes a living enactment of renewal, reminding communities that the year must begin in purity, gratitude, and compassion.

Author’s Note

Songkran weaves together Thailand’s cosmic calendar, Buddhist values, and the simple joy of water. Its blend of reverence and celebration shows how ancient symbolism can endure in modern life. Though its forms have changed, the festival still expresses a deep desire for cleansing, connection, and renewal. In each gentle pour of water and each blessing exchanged, we see a culture honoring both its past and its moral hopes for the year ahead.

Knowledge Check

1. What does water symbolize in Songkran?

Answer: Purification, renewal, and the cleansing of misfortune.

2. What is rot nam dam hua?

Answer: A ritual in which younger people pour scented water over elders’ hands to seek blessings.

3. Why are sand stupas built at temples?

Answer: They symbolize the rebuilding of spiritual strength and returning borrowed earth to sacred spaces.

4. How does Songkran relate to Buddhism?

Answer: It involves merit-making, cleansing rituals, and ethical renewal.

5. Why does Songkran occur in April?

Answer: It marks the solar new year and the seasonal shift toward the rainy season.

6. How have modern celebrations changed the festival?

Answer: They include public water-throwing and tourism, though traditional temple practices remain.