The ʻava ceremony, one of the most distinguished and ancient rituals of Samoa, stands at the heart of Polynesian ceremonial life. Its origins stretch deep into the pre-colonial past, shaped by Samoan social structure, spirituality, and oral tradition. The drink itself, made from the root of the Piper methysticum plant, is one of the most widespread ceremonial substances in Oceania. Yet Samoans developed a uniquely formal and hierarchical ritual around it, a ceremony that honors speech, rank, relationship, and the spiritual breath that binds community together. Whether in the conferring of chiefly titles, diplomatic gatherings, village councils, or high-honor receptions, the ʻava ceremony announces that an event is sacred, orderly, and socially significant.

Description

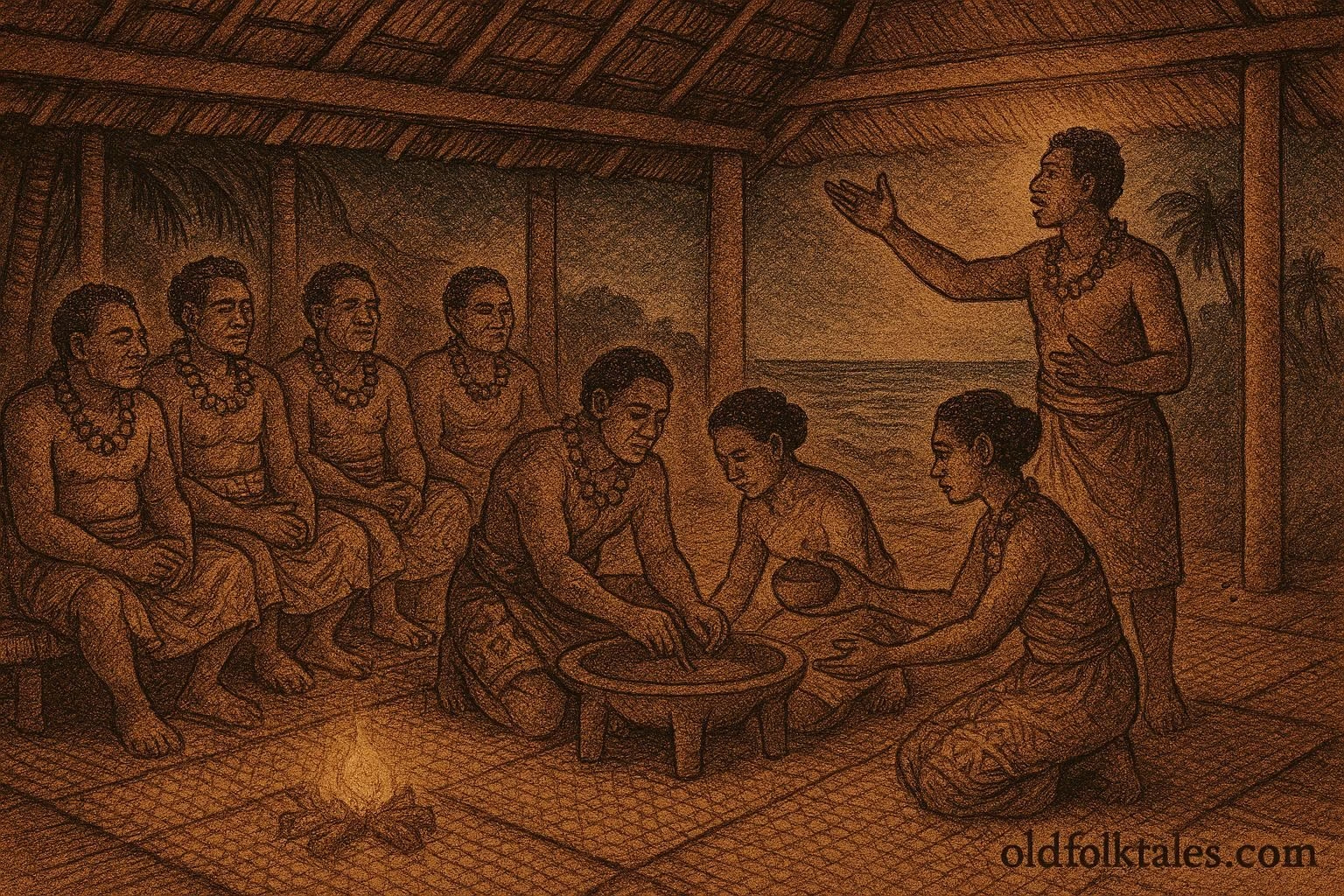

The ʻava ceremony unfolds with steady, deliberate rhythm. Every participant has a defined role, and the ritual sequence reflects Samoa’s intricate system of rank. At its center is the tūlafale (orator chief), who guides the ceremony with formal speech, proclaiming genealogies, blessings, and the meaning of the gathering. Nearby sit the tautua (attendants), whose duty is to prepare the drink and serve it according to custom.

The preparation of the ʻava drink is itself ceremonial. Traditionally, the dried and pounded root is mixed in a large wooden bowl known as the tanoa, carved with sturdy legs that lift it from the ground. Water is added, and attendants knead the mixture with woven fibers. The liquid becomes a cool, earthy beverage with a mild numbing quality. As it is prepared, silence or respectful murmurs often fill the space, for the bowl represents the meeting point of the community and its ancestors.

Beside the tanoa sits the ipu tau ʻava (the coconut shell cup), which will be passed in strict sequence. No cup is ever handed casually. It is raised, saluted, and carried with open palms to the designated recipient. The order of serving, known as the fa‘asamoa, follows a precise hierarchy. High chiefs are served first, then talking chiefs, and so on, until every honored person has received the drink.

When the time comes to serve the first cup, the tautua calls aloud the title of the highest-ranking chief present. The cup-bearer rises with care, walks forward with measured steps, and presents the vessel. The chief accepts it with a slight nod, utters a short blessing or acknowledgment, and drinks in one continuous motion before returning the cup. Applause or formal exclamations mark the acceptance, symbolizing unity and respect.

Throughout the ceremony, speech plays a central role. The orator chiefs deliver eloquent orations filled with metaphor, ancestral references, and ceremonial language. These speeches frame the event, grounding it in the lineage of the participants and the authority of the gods. They remind the gathering that identity in Samoa is rooted in genealogy and human connection. Because of this, ʻava ceremonies are not only ritual acts but cultural archives, the living vessels of history.

The ceremony ends with a closing speech, final sips, and ritual blessings for harmony, safe travel, peace, or the welfare of the community. Through this culmination, the ritual reaffirms the Samoan commitment to mutual respect, social order, and spiritual grounding.

Mythic Connection

Though the ʻava ceremony is a social ritual, its meaning is inseparable from Samoan mythic thought. In Samoan cosmology, the plant itself is seen as a divine gift, connecting humans to the spiritual essence of the land. Oral traditions speak of Tagaloa, a creator deity, who provided the first plants and resources that sustained humanity. The ʻava root is therefore not merely an agricultural product; it is the physical embodiment of a god-given blessing.

Some traditions link the sacredness of ʻava to legendary chiefs whose wisdom and authority were strengthened through ceremonial drink. Because ʻava is associated with clarity, calmness, and steadiness, it became linked to good leadership. A chief who drinks ʻava does so not to seek intoxication but to demonstrate composure, ancestral alignment, and respect for ritual form.

The tanoa bowl itself also carries symbolic depth. Its round shape represents the world and the unity of the village. The legs are sometimes interpreted as genealogical pillars, reminders that every family stands on the strength of its ancestors. Therefore, when ʻava is mixed within the tanoa, the community draws upon its collective spiritual foundation.

The strict serving order teaches the mythic lesson of fa‘aaloalo, respect. In Samoan worldview, harmony depends on acknowledging rank, role, and relationship. The ceremony reenacts the ideal of a balanced universe where order prevents conflict and mutual respect preserves peace.

As Samoa continues to practice the ʻava ceremony today, in universities, parliaments, churches, and chiefly councils, the ritual remains a living manifestation of the mythic values that shaped the islands. It is evidence of how spirituality, respect, and tradition flow seamlessly into Samoan daily life.

Author’s Note

This article explores the ʻava ceremony as a bridge between Samoa’s ancestral world and its modern cultural life. Through its rituals of speech, service, and order, the ceremony reflects the Samoan understanding of respect, genealogy, and spiritual continuity. Its endurance affirms the deep roots of fa‘asamoa and the sacred values that guide Samoan identity.

Knowledge Check

1. What plant is used to prepare ʻava?

The root of the Piper methysticum plant.

2. What is the wooden mixing bowl called?

The tanoa, a carved ceremonial bowl used to prepare the drink.

3. Who guides the ceremony through speech?

The tūlafale orator chief, who offers formal orations.

4. Why is serving order important in the ceremony?

It reflects Samoan social hierarchy and the cultural value of respect.

5. What does the ceremony symbolize spiritually?

Harmony, ancestral connection, and the blessing of the gods.

6. In what contexts is the ʻava ceremony performed?

Chief title bestowals, village councils, formal gatherings, and major cultural events.