The New Fire Ceremony, called Xiuhmolpilli (“the binding of the years”), emerged among the Late Postclassic Mexica of central Mexico. It marked the completion of the 52-year “calendar round,” when the 260-day ritual calendar aligned with the 365-day solar calendar. This rare convergence carried deep cosmic meaning. The Mexica viewed it as a threshold moment when the universe stood vulnerable to collapse. Priests, communities, and rulers responded with a ritual that renewed the sun’s journey and affirmed human devotion.

Description

The ceremony began with a striking act: every household fire was extinguished. The city fell into a purposeful darkness that symbolized the end of the old cycle. People cleaned their homes, broke old household items, and fasted. These actions marked detachment from the previous era. Priests urged calm, though people feared the possibility of cosmic failure. If the ritual did not succeed, the sun might not rise again.

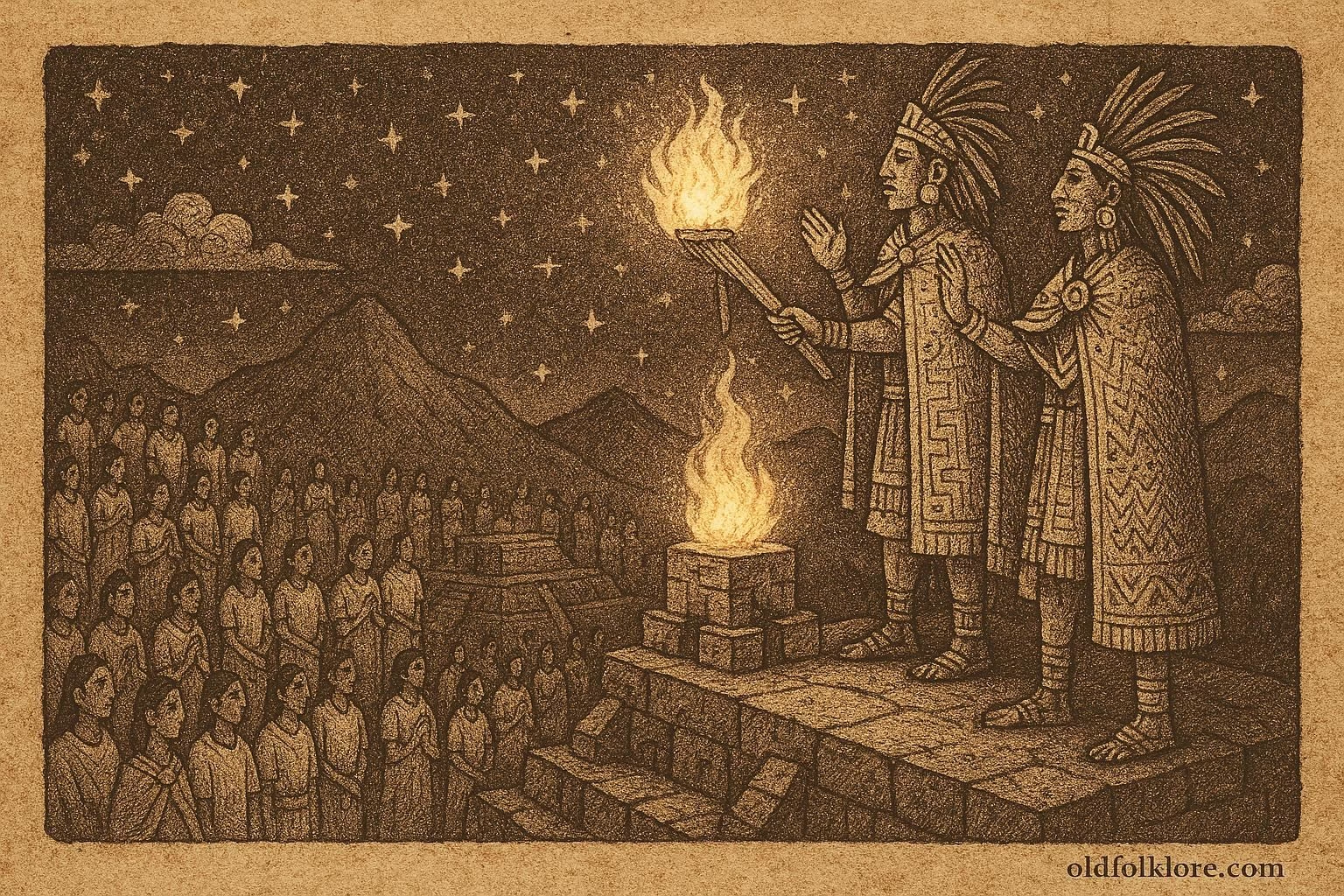

As night deepened, a sacred procession moved toward a mountaintop, often the Hill of the Star, known in Nahuatl as Huixachtlan. Religious specialists climbed in quiet formation. They carried sacred bundles, calendrical instruments, and offerings. Meanwhile, families waited in their homes. They looked toward the ridge and searched for the spark that would determine their fate.

At the summit, the priests watched the sky. They awaited the exact moment when the Pleiades crossed the zenith. Their timing required astronomical knowledge accumulated over generations. When the stars reached their appointed position, the priests acted quickly. They opened the chest cavity of the sacrificial victim and drilled the new fire upon a sacred wooden board placed above the heart. The first ember appeared. If the flame caught, the cosmos endured.

As soon as the fire grew strong, messengers ran toward the capital. From the mountaintop the new flame traveled in guarded torches. Temples relit their hearths, beginning with the flame at the Templo Mayor dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. Priests then distributed the fire to surrounding neighborhoods. Each household reignited its hearth from this divine source. In this act, homes symbolically reattached themselves to the sacred center.

The following day brought renewal. People discarded worn clothing and donned new garments. They repaired altars, swept streets, and held communal feasts. Movement, color, and noise replaced the quiet tension of the previous night. The new era began with confidence because the sun had entered another cycle of strength.

Mythic Connection

The New Fire Ceremony rested on a central fear: the sun might fail. In Aztec cosmology, previous worlds had ended violently. Each age relied on sacrifice to empower the sun. The New Fire reenacted these mythic truths. By extinguishing fires, the people acknowledged the fragility of creation. By kindling a single flame at the appointed moment, priests ensured the sun would continue its path.

Fire deities shaped the ritual. Xiuhtecuhtli, Lord of Fire and Time, stood at its core. His presence governed warmth, household stability, and cosmic endurance. Huitzilopochtli, the patron of the Mexica, added martial and political weight. Through the New Fire, the state broadcast divine legitimacy. The ceremony said clearly that the Mexica maintained order not only on earth but in the heavens.

The Pleiades served as cosmic markers. Their position in the sky signaled whether the world would survive. Thus astronomy became mythic language. Knowledge of the stars allowed priests to translate divine intention into human action. When the flame ignited, myth and science blended into a single theological truth: renewal was possible.

How the Ritual Reflected Cultural Values

This ceremony expressed the Mexica worldview in several ways. First, it affirmed reciprocity between humans and gods. People offered sacrifice; gods granted stability. Second, it reinforced social hierarchy. Only trained priests and chosen officials stood at the mountaintop. The public watched and responded, trusting divine specialists to mediate cosmic danger.

Third, the ritual united the empire. Towns were required to participate and receive fire from the capital. This political dimension strengthened imperial identity. Finally, the ceremony marked time in a sacred way. A new era did not begin with a date on a calendar but with a dramatic, embodied event witnessed by all.

Author’s Note

This article summarizes the Aztec New Fire Ceremony as a ritual of cosmic renewal rooted in astronomy, sacrifice, and communal devotion. It highlights how the Mexica bound social order to celestial cycles and affirmed their relationship with the gods through the rekindling of a single flame.

Knowledge Check

1. What did the extinguished fires symbolize?

They marked the end of the old 52-year cycle and the uncertainty before renewal.

2. Why were the Pleiades essential to the ritual?

Their zenith position signaled the safe moment to ignite the new flame.

3. What deity governed fire and cosmic endurance?

Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec Lord of Fire and Time.

4. How did households receive the new flame?

Priests carried it from the mountaintop to temples, then to each neighborhood.

5. Why was the ritual politically significant?

It unified towns under Mexica authority and reaffirmed state power.

6. What fear motivated the New Fire Ceremony?

The fear that the sun might fail and the world collapse without renewal.