Vodun is the ancient spiritual system of the Fon, Ewe, and related peoples along the West African coast. Rooted in pre-colonial kingdoms such as Dahomey, it served as the foundation of social structure, moral order, and cosmological insight. The modern Fête du Vodoun, officially celebrated each year on January 10 in Benin, emerged as a national affirmation of indigenous religion after decades of suppression. Today, it unites priests, devotees, royalty, and international diaspora communities in Ouidah, Porto-Novo, and villages across Benin and Togo.

Description

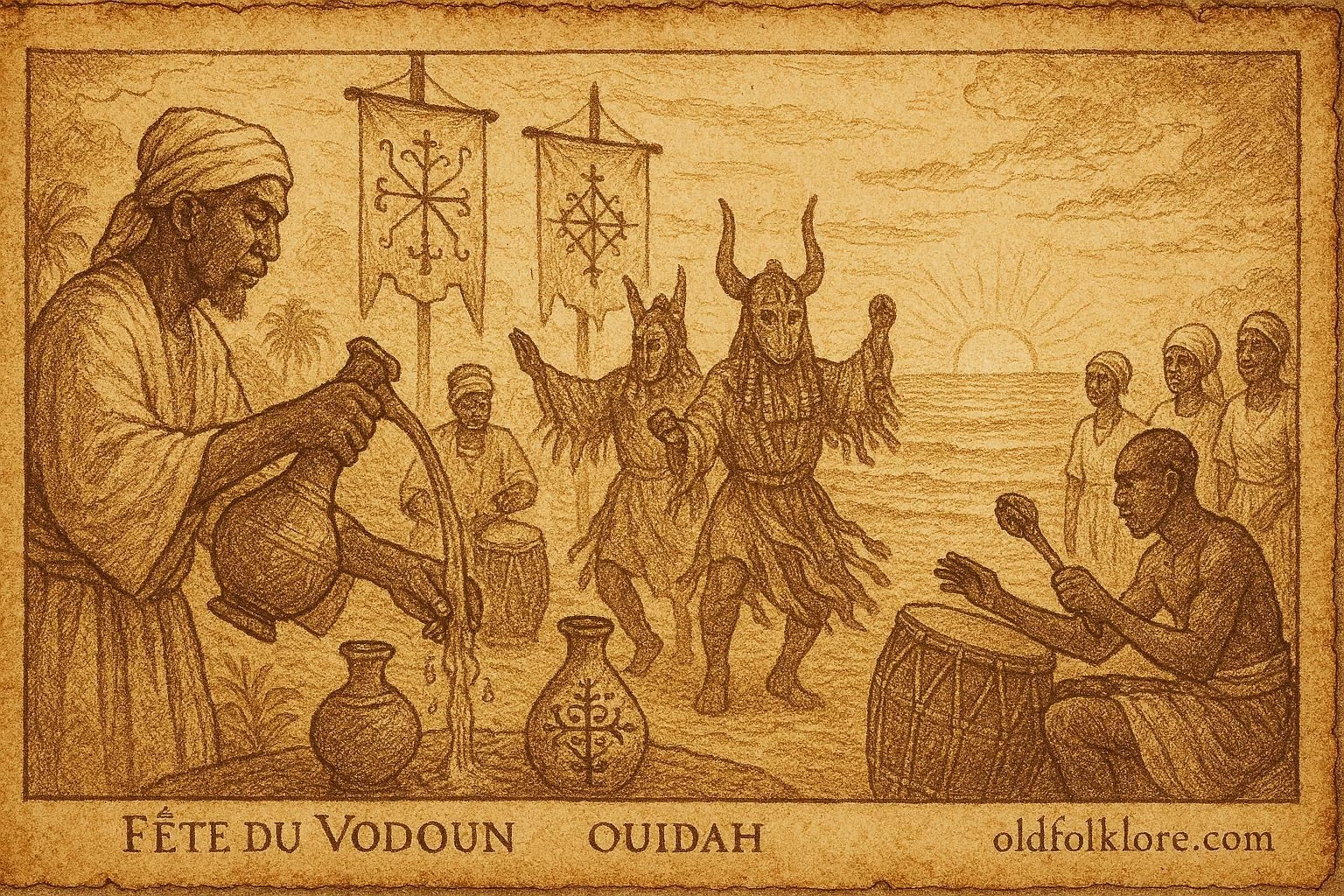

Every January, the coastal city of Ouidah transforms into a vibrant spiritual landscape where the living and the spirit world meet openly. Streets fill with drumming, white-robed devotees, ancestral banners, and priestly processions. Although the celebration is public, its roots lie in deep ritual structures that have guided communities for centuries.

The festival begins with purification rites. Priests known as bokonon and vodunsi stand before shrines, performing libations with gin, palm wine, and water. Each gesture seeks to cool the spirits, open the ritual year, and prepare the path for the arrival of the Vodun, the powerful deities and forces governing nature, fate, and ancestral continuity. Offerings of chalk, kola nut, flour, and animal sacrifice may follow, depending on the community’s tradition.

As drummers strike the polyrhythms of kpanlogo, agbadja, and other regional styles, processions move toward sacred sites. One of the most iconic routes leads to the Temple of Pythons in Ouidah. Snakes associated with the deity Dan (or Dàn) symbolize continuity, protection, and the cyclical nature of life. Devotees enter the temple to honor the serpent spirits, asking for guidance or healing.

Another procession travels to the beach, a symbolic threshold between worlds. Here, the Atlantic Ocean becomes a vast ritual mirror. Many participants pour libations into the water to honor maritime spirits and to acknowledge ancestors taken across the ocean during the Atlantic slave trade. This act—quiet, solemn, and filled with layered meaning, connects the festival to African diaspora religions in Haiti, Brazil, Cuba, and the American South.

During the day, performances unfold in ceremonial arenas. Masked dancers embody specific Vodun spirits. Zangbeto, the night-guardian spirit, emerges as a swirling, towering raffia form that spins with supernatural energy. Traditionally, Zangbeto protects the community and reveals hidden truths. When it dances, crowds gather in awe. Other groups present Egungun, the masked ancestors whose fluttering cloth layers represent spiritual presence. Through these performances, the festival becomes a moving theatre of cosmology, each dance recounting a myth or spiritual role.

Possession rituals often form the heart of the ceremony. To outsiders, they may appear dramatic, bodies trembling, voices shifting, faces altered by trance, but for practitioners, possession is a sacred moment when a Vodun spirit enters the human vessel. The possessed individual becomes a medium, conveying messages, warnings, or blessings. Devotees treat these messages with reverence, for they reflect the will of forces older than human memory.

Throughout the day, offerings continue. Food is shared widely, reflecting the communal nature of Vodun practice. Families cook yam, maize, fish, and palm-oil dishes to give thanks to both ancestors and living kin. This communal feasting reinforces spiritual belonging: nourishment becomes a sacred exchange between the visible and invisible realms.

Although the modern festival attracts tourists, its meaning for local communities remains spiritual rather than performative. Elders remind visitors that Vodun is not a spectacle but a cosmological system. It binds people to the land, the sea, and the lineage of ancestors who shaped the region’s history. Every drumbeat, chant, and libation reaffirms this identity.

Variations exist across Benin and Togo. Some communities emphasize storm-related spirits like Hevioso (god of thunder), while others foreground river spirits such as Mami Wata. Liturgical languages differ; songs may be performed in Fon, Ewe, or Gun. Yet the underlying structure—honoring deities, ancestors, and the natural world, remains constant. The festival’s diversity demonstrates Vodun’s adaptability and its ability to preserve core meaning while expressing local heritage.

In recent decades, diaspora communities have joined the festival, reconnecting with a tradition that helped form Haitian Vodou, Cuban Lucumí, Brazilian Candomblé, and African American root-working traditions. This exchange enriches the ceremony, creating a bridge across continents. Thus, the Fête du Vodoun becomes more than a festival; it becomes a living archive of spiritual continuity.

Mythic Connection

Vodun teaches that every element, earth, sea, thunder, fertility, ancestors, has a spiritual force. During the festival, these forces become visible through dance, possession, and ritual. The ceremonies reenact creation myths in which supreme powers shape the world through balance and interdependence. By honoring these powers, devotees reaffirm their place within a sacred cosmic structure.

Author’s Note

This study of the Fête du Vodoun explored its origins, ritual forms, symbolic acts, and cosmic meanings. The festival stands as a living system linking spirits, ancestors, and community identity across generations.

Knowledge Check

1. What cultures practice Vodun?

Primarily the Fon, Ewe, and related West African coastal groups.

2. Why is January 10 significant?

It marks Benin’s National Vodun Day, honoring traditional religion.

3. What role do processions play?

They guide devotees to shrines, beaches, and sacred sites for offerings.

4. What does spirit possession signify?

A Vodun deity temporarily enters a devotee to convey messages or blessings.

5. Why is the ocean important in the festival?

It symbolizes spiritual thresholds and honors ancestors lost to the Atlantic slave trade.

6. What makes Vodun ceremonies diverse?

Local pantheons, liturgical languages, and ritual emphases vary by region.