The Wiindigoo, also known as the Wendigo, Wihtikow, or Witiko, is one of the most enduring and fearsome figures in North American Indigenous oral tradition. Found throughout the vast boreal and subarctic forests of the Algonquian-speaking peoples, the Wiindigoo is a spirit of famine, isolation, and unrestrained hunger. Its tales echo across Ojibwe, Cree, and Innu communities, always warning of what happens when human need transforms into monstrous greed.

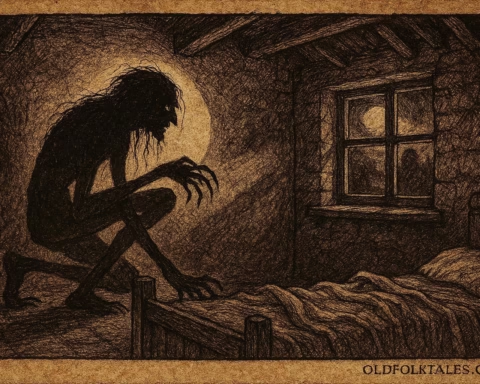

In classical ethnographic records, the Wiindigoo is described as gaunt and skeletal, its skin stretched tightly over its bones, sometimes ice-crusted, sometimes gray and corpse-like. Its heart, according to some tellings, is made of ice, symbolizing the cold of hunger and the absence of warmth or compassion. Its mouth drips with blood or frost, and its breath freezes the forest air. Others describe it as gigantic and emaciated, its body growing larger the more it eats, yet never full. In many oral narratives, its presence is heralded by bitter winds or the creaking of trees in deep winter nights.

Journey through the world’s most powerful legends, where gods, mortals, and destiny intertwine

The creature’s powers vary across traditions but share a moral and cosmological unity: the Wiindigoo devours not only flesh but spirit. It can possess humans, driving them to acts of cannibalism and moral transgression during times of starvation. In other stories, a human who commits the forbidden act of eating another person becomes a Wiindigoo, cursed to wander the frozen wilderness, eternally hungry and divorced from kinship and community.

A fragment from an early academic note captures the idea succinctly:

“The wihtikow (windigo) marks the point where human hunger turns to monstrous appetite.”

Thus, the Wiindigoo is not merely a monster, it is the living embodiment of the moral threshold that separates humanity from chaos.

Behavior and Mythic Role

The Wiindigoo is both predator and warning. It roams the snow-laden forests, hunting those who travel alone or break the social bonds of sharing. When famine strikes a village and food grows scarce, tales of the Wiindigoo intensify. It appears as a mirror to human desperation: whoever yields to hunger’s darkest call risks losing their humanity.

Among the Ojibwe, Cree, and Innu, these stories teach survival ethics. During harsh winters, when starvation loomed and the temptation to break taboos grew strong, storytellers invoked the Wiindigoo to remind people of the sacred duty to share, to stay within the warmth of community, and to resist isolation.

In certain Cree traditions, shamans or healers could confront or drive out the Wiindigoo spirit through rituals, burning sage, or using iron objects. In some regions, wiindigookaanzhimowin, ritual dances or performances, symbolically re-enacted the defeat of the spirit, reinforcing communal bonds.

Yet, not all Wiindigook were evil. Some legends tell of Windigo hunters, humans who, after confronting and destroying a Wiindigoo, gained spiritual insight into the nature of hunger and restraint. Others suggest that shamans could take on Wiindigoo-like power temporarily to protect their people from starvation, walking the fine line between self-sacrifice and corruption.

Cultural Role and Symbolism

The Wiindigoo’s symbolic range is vast. At its core, it personifies hunger without balance, a cosmic warning against greed, selfishness, and the erosion of social harmony. In a spiritual sense, the Wiindigoo is not merely about cannibalism; it is about consuming more than one’s share, of food, wealth, or power.

In Algonquian cosmology, moral health depends on reciprocity and respect for balance: between humans and nature, between individuals and community. The Wiindigoo stands as the ultimate perversion of that harmony. Its endless hunger reflects the dangers of hoarding resources, breaking communal laws, or exploiting others for personal survival.

The Wiindigoo also serves as a seasonal spirit, tied to winter’s severity. It embodies the deadly beauty of cold, its purity and its peril. Many stories locate the Wiindigoo’s lairs in frozen lakes or deep snowfields, where it waits for the lost or desperate. The coming of spring, and the thaw of ice, often marks its retreat, a cycle mirroring death and renewal in nature.

Scholars have debated the colonial-era term “Wendigo psychosis,” a controversial psychological label once applied to Indigenous individuals during starvation crises. Modern Indigenous and academic voices criticize this as a misunderstanding of the Wiindigoo’s cultural logic: the figure is not a mental illness but a moral metaphor, rooted in survival ethics and communal identity.

Through centuries of retelling, the Wiindigoo has remained a moral compass, pointing to what happens when one forgets that human life depends on restraint, sharing, and respect for the living world.

Encounter dragons, spirits, and beasts that roamed the myths of every civilization

Author’s Note

In studying the Wiindigoo, one must approach not as a horror myth but as a moral cosmology. Western collectors like Henry R. Schoolcraft often recorded these tales through colonial lenses, trimming or moralizing details to fit European expectations of “savage superstition.” Yet beneath these distortions lies a sophisticated ethical philosophy, an ecological code embedded in narrative form.

To the Anishinaabe and their linguistic kin, the Wiindigoo is not a fantasy but a teaching story that preserves the law of survival: humanity exists only through generosity. The Wiindigoo reminds us that the true famine is spiritual, the hunger that comes when one forgets connection, empathy, and the rhythm of sharing that sustains life in a harsh world.

Knowledge Check (Q&A)

- Q: What core moral lesson does the Wiindigoo symbolize?

A: The danger of greed and isolation, the loss of humanity through selfish hunger. - Q: In which season is the Wiindigoo most active, and why?

A: Winter, symbolizing famine, isolation, and moral testing. - Q: What act commonly transforms a human into a Wiindigoo in traditional stories?

A: Committing cannibalism during starvation. - Q: How did communities traditionally guard against the Wiindigoo’s influence?

A: Through sharing food, maintaining social bonds, and performing cleansing rituals. - Q: What cultural misunderstanding did colonial ethnographers introduce regarding the Wiindigoo?

A: The concept of “Wendigo psychosis,” which pathologized cultural myth rather than understanding its moral symbolism. - Q: What element of nature is most closely associated with the Wiindigoo’s heart and essence?

A: Ice, symbolizing spiritual coldness and endless hunger.

Sources:

Primary Source: Henry Rowe Schoolcraft Papers, Library of Congress (19th c.)

Secondary Source: “Cannibal Wihtiko: Finding Native–Newcomer Common Ground” (comparative analysis)

Origin: Anishinaabe, Cree, Innu, and other Algonquian-language peoples of North America